That should be sufficient material for today! especially since we need to cover: 1 Two mistranslations, and 2 A clause which we might wish weren’t there (and I think you know which one I mean), but it is, so I guess we’ve got to deal with it.

Give us this day our daily bread.

This is a plea to God to provide our material needs. Right? Wrong. We need to do some linguistic analysis here. Sorry, but this is important.

The issue is with the adjective “daily”, which was an English Reformation translation of the Greek word ἐπιούσιον”: “Give us today our epiousion bread”. “Epiousios” does not mean “daily”. It means… well, there’s the problem. “Epiousios” apparently is a word found nowhere else, not in classical Greek, not in popular Greek, not elsewhere in the Greek New Testament – only here. It seems to have been “invented” for use in the “Our Father”, probably to try to convey the sense of what Christ originally said.

“Epiousion” is at 0.19 below.

courtesy of Grammatika Publishers

Jesus usually spoke in Aramaic, the popular language of Palestine. Here is the “Our Father” is present-day liturgical Aramaic:

From “Adoration of the Cross” Blog, which is preserving ancient Christian music and could use some financial assistance. Go to: https://www.patreon.com/AOTC

But are these the words Christ spoke? The commentary accompanying the video points out that Jesus spoke the Galilean dialect of Aramatic, with which we have completely lost touch. So we do not know the exact words of the Lord’s Prayer as He delivered it. And as you know, many words do not translate precisely from one language to another.

So what we seem to be left with is the Greek “epiousios”

Next question: How do we translate “epiousios” into English? Many say the best word might be “super-substantial” (“above and beyond the material substance” of bread). Unfortunately that also requires explanation. (I never told you this was going to be easy…)

“Super-substantial” bread seems to allude to:

1 Jesus’ answer to Satan during His great temptations: “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.’” Matthew 4:4

2 “For the bread of God is the bread that comes down from heaven and gives life to the world…” John 6:33

3 “I am the Bread of Life. He who comes to Me shall never hunger”. John 6:33-35

4 “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats this bread will live forever. This bread is  my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world.” John 6:51

my flesh, which I will give for the life of the world.” John 6:51

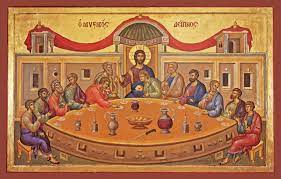

By permission of Saint Isaac’s Skete at skete.com

5 I think the most significant is this: “He took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is My body which is given for you; do this for the remembrance of Me.’” Luke 22:19

6 I suspect our best clue to how the early Church understood “epiousios” may come from where the “Our Father” was placed in (I think) every Christian Liturgy: immediately before the faithful receive the Holy Eucharist, “the Bread of Heaven”.

So how could we best put that unique word “epiousios” into understandable English, without using a dozen words to explain? I’d suggest: “Give us today the Bread of Heaven”, or perhaps “Give us today the Bread of Life”, or Give us today the Living Bread”. But that’s only my opinion, which may be wrong.

Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.

“Oh, Lord Jesus, why didn’t you just give us ‘Forgive us our trespasses’ and stop there? But no, You had to go on and add ‘as we forgive those who trespass against us.'”

This is the most threatening, indeed terrifying, part of the “Our Father” – and we say it so casually.

Just in case his hearers weren’t praying attention, Our Lord spelled it out even more clearly immediately after He delivered the Lord’s Prayer: “For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.” Matthew 6:14-15

Anonymous, German c 1560 (Webb Gallery)

Or take the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant, where the Master returns and says: “‘You wicked servant! I forgave you all that debt because you begged me. Should you not also have had compassion on your fellow servant, just as I had pity on you?’ And his master was angry, and delivered him to the torturers until he should pay all that was due to him. So My heavenly Father also will do to you if each of you, from his heart, does not forgive his brother his trespasses.” Matthew 18:21-35

That seems clear enough. If we do not forgive, off we go to the torturers!

Here comes a little more word analysis. I’ll spare you the Greek letters this time.

“Trespasses” also came out of the English Reformation. Most scholars say it doesn’t quite “cut it”, that the more accurate translation is “Forgive us our debts“, as in the Parable above. The question then is: What do we owe to God? The answer is simple: Everything. “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and mind and strength: and your neighbor as yourself”. 24/7/365. And if at any moment in any way we fall away from love of God and love of each other, we can never get that moment back. It’s a debt we can’t possibly repay. All we can do is pray “Forgive me my debts”.

The Greek word here for “forgive” means to “send away”, “remove”, as in the Parable of the Wicked Servant, God forgives us our debt. And if we then won’t forgive others, who exactly do we think we are? better than God?

Or take the Parable of the Prodigal Son: Before his son could say “I’m sorry”, the father ran out to make it clear that he would forgive. Likewise God the Father “ran out to us” in our Lord Jesus Christ. “God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” Romans 5:8 God never says to us “Pay what you owe me”.

Or take the Parable of the Prodigal Son: Before his son could say “I’m sorry”, the father ran out to make it clear that he would forgive. Likewise God the Father “ran out to us” in our Lord Jesus Christ. “God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” Romans 5:8 God never says to us “Pay what you owe me”.

courtesy of Greek Archdiocese

But what about the second clause: “If God has already forgiven me, why must I forgive others? Will He take it back if I don’t?” Consider this “angle”: What if our heart is so hard, so closed off, that we cannot accept His love and forgiveness? Actually this should be titled “The Parable of the Prodigal Sons“, for at the end of it the elder Brother is refusing to forgive his brother, turning away from his father and his family. And now who was the prodigal? Now who was cutting himself off from his father? We may hope that the elder son came to his senses and returned to his father, who was certain to welcome him back – but did he? Will we? The parable doesn’t tell us.

Another point: We need to forgive not chiefly for the sake of the person who sinned against us. (He or she may not even be sorry – the rat!) It’s for our own sake. If we hang onto hurts and anger and grudges, it destroys our inner life. I don’t have to spell this out for you, do I? We all know what it feels like: When we’re angry at someone, it interferes with our prayer life, our ability to think straight and concentrate on good things. It tears the love out of our heart.

Unless we “forgive from our hearts”, it takes over ever more of our lives and it makes us ever more miserable and self-absorbed – and that is the beginning of the torture promised for us if we do not forgive. Is this sometimes hard to do? Yes! Terribly hard. But if we cannot… … I was going to say “it will kill our soul”. Oh, it’s worse than that. If we don’t lay it down, get rid of it, our torture will continue into eternity, and there in Hell we will wish it had killed our soul.

On Forgiveness Sunday, 2008, I wrote a great deal more about the “practicalities” of forgiving and how to do it. If you wish, see: https://frbillsorthodoxblog.com/2018/02/14/52-forgiveness-sunday/

And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.

James, Brother of the Lord and First Bishop of Jerusalem, wrote: “Let no one say when he is tempted, ‘I am tempted by God’; for God cannot be tempted by evil, nor does He Himself tempt anyone.” James 1:13 So why does Christ tell us to pray the Father: “lead us not into temptation”?

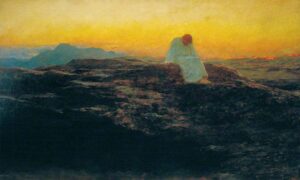

Briton Riviere, 1898 (Public Catalog Foundation)

Briton Riviere, 1898 (Public Catalog Foundation)

There have been many attempts to reconcile these two passages, which I don’t find convincing. I think the answer is found here: “Then Jesus was led by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” Matthew 4:1

This took place just before Christ began His public ministry. He will have only three short years to accomplish all He has been sent to do. So here God the Holy Spirit leads Him out to be tempted by Satan, so He will resist and “get His priorities straight” (as we now might say) before He launches into it.

Surely God also leads us into temptation in this way. At various times, as we can handle it, God allows that dreadful Being to come at us, so we can have the opportunity to resist and grow and become strong – or not, in which case we may become wiser. “We also glory in tribulations, knowing that tribulation produces perseverance; and perseverance, character; and character, hope. Now hope does not disappoint, because the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit who was given to us.” Romans 5:3-5 But first, Paul says (and I wish it were otherwise), we need to suffer “tribulations”.

Ultimately there is only one source of tribulations – and that leads us to the chief point of this clause. The Greek does not say “Deliver us from evil”. It says deliver us from “the evil” (τοῦ πονηροῦ), which makes sense only if it is translated “from the evil one”, the devil.

So the meaning of the whole section is: “Lead us not into temptation [as you led Christ out to be tempted], “but deliver us from the evil one” [as Christ was delivered from the devil’]. Or at least that seems obvious to me.

Do you believe in Satan? the Evil One? Oh, how could you not? I mean, God is good, but look at state of the world. Look at yourself. Look at me.

Notice the experience of being tempted. At least with me, it’s not like I think it through rationally and conclude, “Now I will do this stupid thing”. It’s not like that at all. Rather it’s something that comes at me, comes over me, and if I don’t fight it off, I fall into it. Actually it feels as if someone is coming at me, over me.

The consistent teaching of Jesus Christ and the New Testament and the Church is that it is indeed someone – who is out to get us, lead us astray, destroy us. Our Lord Jesus Christ first stressed this radical, frightening concept of Satan in our Judaeo/Christian Tradition. In the Old Testament we find very little about Satan, and there he’s nowhere near as scary as what Jesus taught. For example, “I will show you whom you should fear: Fear him who, after he has killed, has power to cast into hell; yes, I say to you, fear him.” Luke 12:5 And the Church ever since has followed Him in this.

“Be sober, be vigilant; because your adversary the devil walks about like a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour. Resist him, steadfast in the faith…” 1 Peter 5:8-9

Russian Orthodox Chant sung by the Russian Chorus – Углич Ковчег

“For thine is the Kingdom and the Power and the Glory…”

These words were not part of the “Our Father” as Christ delivered it to us. However, from the beginning liturgists in the Church have felt the need to conclude the Prayer at Divine Liturgy by glorifying God. The words have varied from place to place. However, I think that in all traditional Liturgies, this doxology has been reserved to the presiding bishop or priest, so that the people say only the Prayer given us by the Lord. Orthodox never use the Doxology except at Divine Liturgy.

So here, in my opinion, is how the Lord’s Prayer should read:

“Our Father in Heaven, Holy be Your Name, Your Kingdom come, Your will be done on earth as it is in Heaven. Give us this day the Bread of Life [or Bread of Heaven]. And forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.”

But don’t you ever say it aloud in church like that! First, because that reading is only my personal opinion. Second, because you’ll only make a commotion. People will stare at you. So pray with the people – except perhaps quietly say “the Evil One“.

But then from time to time, please remind yourself what the “Our Father” means. Don’t just rattle it off – the way I usually do, and I’m trying to break that habit.

courtesy of Coptic Orthodox Archbishop Angaelos of London

Next Week: The Wonders of Saint Nicholas

Week after Next: John of Damascus – a Saint who was “Chief Counsilor” to a Muslim Caliph, who protected him from the Christian Emperor of Constantinople!

Thank you for another enlightening post, Father Bill.

FYI, my wife and I end Our Lord’s Prayer with ” . . . the evil one”, during liturgy, and, a few times, a person who heard us say it said a complimentary remark.

In our Greek Orthodox church, we do end with “the evil one”, which, when I first heard it, made so much sense to me! I am working on learning the prayer in Greek, for this senior is not an easy task, haha. Our priest invites all to say the prayer in their own language…Greek (of course), English, Spanish, Russian, Serbian, Amharic are the ones we often hear. It is lovely and inspiring.

Thanks Yvonne and John. I think this is the way the Orthodox Church usually changes – from the people up.

However, advice for others, regarding the “Our Father” and anything else: Try to move with your priest and parish, regarding “the evil one” and anything else. Speak with your priest about it. Talk with others about it. That’s more effective than making show of it doing it by yourself.