Before we plunge into this Post: May God grant you a blessed feast of the Holy Angels today, and of that wonderful Saint Nektarios tomorrow. And praise Him for sending them to help and assist us. [P.S. on Friday evening. I forgot to add: Go to Post 91 to read the life of Holy Nektarios.]

Before we plunge into this Post: May God grant you a blessed feast of the Holy Angels today, and of that wonderful Saint Nektarios tomorrow. And praise Him for sending them to help and assist us. [P.S. on Friday evening. I forgot to add: Go to Post 91 to read the life of Holy Nektarios.]

The Preparation, Part Two

We’re still looking at what I called “The Hidden Liturgy”, the part of the Divine Liturgy which few Orthodox have ever seen because it takes place some while before the Public Liturgy begins.

Last week we covered the first two parts of this Liturgy of Preparation: 1 The Prayers of the Clergy before the Iconostasis. 2 The Vesting of the Clergy.

Now we move on to the most important part.

3 The Proskimidi

This is the Preparation of the Holy Gifts – the Holy Bread and Wine for consecration during the Anaphora of the public Divine Liturgy.

This is the Preparation of the Holy Gifts – the Holy Bread and Wine for consecration during the Anaphora of the public Divine Liturgy.

Proskimidi / Προσκομιδή means “Preparation”. This service is sometimes called the Prothesis / πρόϑεσις which means the “setting forth” of the Holy Gifts. It takes place usually in the Altar on a table to the left of the Holy Table.

The Prosphoron / πρόσφορον (“offering”), or Prosphora when more than one are used, is the Holy Bread which now is about to be identified with the Sacrifice of our Lord Jesus Christ. The Bread and Wine are treated with reverence from this time forward – even before the formal consecration. Father Alexander Schmemann made the point that in the Orthodox understanding, there is no single moment that consecrates the Holy Gifts, but rather the whole Liturgical “action” does it, beginning with the Preparation. The Epiklesis of the Holy Spirit is only the “focus” of the consecration, so to speak. More on that later in this series.

The Prosphoron is a round loaf, leavened with yeast. * Usually it is baked by someone from the congregation using a traditional recipe, though it may also be purchased from an Orthodox bakery. Those who give the Prosphora always include a list of living and departed for whom they wish prayers to be offered.

is a round loaf, leavened with yeast. * Usually it is baked by someone from the congregation using a traditional recipe, though it may also be purchased from an Orthodox bakery. Those who give the Prosphora always include a list of living and departed for whom they wish prayers to be offered.

- Western Christians (Roman Catholic and Anglican) use unleavened wafers for Holy Communion. Why? I’ve never found a clear explanation. I read a column which claimed that the early Church followed the tradition of the Jewish matzo bread used at the Seder, and that this has continued in the West – while the Orthodox Church first began using leavened bread in the 12th or 13th century. It sounds like a good explanation – except that it’s not true! The Orthodox Church has always used leavened bread.

I once heard an Anglican liturgical scholar say it was hard enough to convince people that the bread is the Body of Christ, without also having to convince them that it is bread! (He said it, not me.)

I once heard an Anglican liturgical scholar say it was hard enough to convince people that the bread is the Body of Christ, without also having to convince them that it is bread! (He said it, not me.)

The Preparation of the Holy Gifts

First the Priest uncovers the Holy Bread, then he (or the Deacon, if present) pours wine and water into the Chalice, with a blessing. Why water? Probably because anciently people never drank wine without first “cutting” it with water.

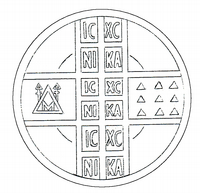

The Bread has a “seal” on the top. See above. A clearer picture is below. The Priest takes a knife, which is used for this purpose only, and begins to cut the Bread. First he cuts out and removes the center square from the Prosphoron and places it on an “elevated” plate called the Diskos. (Western Christians use a flat plate called the “paten”.) This is called the “Lamb”. It is what will be consecrated to become the Body of Christ. Christ is the Lamb of God, the Paschal sacrifice.

In the prayers we identify this Bread with Christ’s Body given for us: “And as a spotless Iamb is silent before his shearers, so opened he not his mouth.” Isaiah 53:7 And finally: “Sacrificed is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world, for the life of the world and its salvation”. The Priest places the Lamb in the center of the Diskos.

Then taking the rest of the Prosphoron, the Priest begins to “construct” an image of the Church. Christ is in the center. Then on the left, (Christ’s right, so so speak, since He is the King, facing us) he places a small triangular piece of the Bread symbolizing the Mother of God. Then on Christ’s left, nine particles commemorating the seven categories of saints  (holy angels, prophets, apostles, fathers, martyrs, ascetics, unmercenary physicians) and then the saints of the day, and finally the author of the Liturgy to be celebrated (Saint Basil the Great or Saint John Chrysostom).

(holy angels, prophets, apostles, fathers, martyrs, ascetics, unmercenary physicians) and then the saints of the day, and finally the author of the Liturgy to be celebrated (Saint Basil the Great or Saint John Chrysostom).

Next the Priest places, immediately at the bottom of the Lamb, a particle of Holy Bread: 1 for each living person he wants to pray for – beginning always with the Metropolitan or Archbishop and the Bishop of the local Diocese, then the Bishop who ordained him, and his sponsors in ordination and those whom he has sponsored, 2 for his own loved ones and friends, followed by those whom any clergy or anyone else present wish to pray for, 3 for those on the list given by those who provided the Prosphora, 4 for whoever else has asked for prayers, * 5 and at Saint Nicholas (we can do this because we do not have a large congregation) we add a particle for each member or family of our parish and each former member and all who support us in any way. So all of us are there on the Diskos every Sunday. We have a very “crowded” Diskos!

- Some say only Orthodox Christians should be “on the Diskos”. I disagree. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote that there may be many who are part of the Church (God’s people) whom God knows but we do not – the invisible Church, so to speak. So I prefer to let God sort it out. Feel free to comment below if you think this is wrong.

Then at the far bottom of the Diskos the Priest does the same for the departed, following the same pattern. * And last, at the extreme bottom of the Diskos, the Priest places one small particle for himself with the words, “Remember, O Lord, my unworthiness, and forgive all my offenses, both voluntary and involuntary.”

Then at the far bottom of the Diskos the Priest does the same for the departed, following the same pattern. * And last, at the extreme bottom of the Diskos, the Priest places one small particle for himself with the words, “Remember, O Lord, my unworthiness, and forgive all my offenses, both voluntary and involuntary.”

- Oh, dear God, the number of particles for my departed loved ones is now so great.

So there on the Diskos is the Church, the Holy Body of Christ – Christ in the middle, and his people, both the saints and the rest of us, both living and departed, gathered around him.

Finally with  appropriate prayers the Priest covers the Holy Bread with the asterix (a four-pronged cover) for protection, and then

appropriate prayers the Priest covers the Holy Bread with the asterix (a four-pronged cover) for protection, and then  both the Chalice and the Diskos with veils for protection. He censes it all, then concludes with a final prayer: “O God our God, who didst send forth the heavenly Bread, the food of the whole world, our Lord and God Jesus Christ, our Savior and Redeemer and Benefactor, blessing and sanctifying us: Do thou thyself bless this Oblation and receive it upon thine altar above the heavens. Remember, as Thou art good and lovest mankind, those who brought this offering and those for whom they brought it; and preserve us blameless in the celebration of thy holy Mysteries; for sanctified and glorified is Thy most honorable and majestic name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen.”

both the Chalice and the Diskos with veils for protection. He censes it all, then concludes with a final prayer: “O God our God, who didst send forth the heavenly Bread, the food of the whole world, our Lord and God Jesus Christ, our Savior and Redeemer and Benefactor, blessing and sanctifying us: Do thou thyself bless this Oblation and receive it upon thine altar above the heavens. Remember, as Thou art good and lovest mankind, those who brought this offering and those for whom they brought it; and preserve us blameless in the celebration of thy holy Mysteries; for sanctified and glorified is Thy most honorable and majestic name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen.”

Later, during the Great Entrance of the Divine Liturgy, the Priest will carry this image of the Body of Christ (and so will carry us) up to the Altar – where the Bread on the Diskos will become the Body of Christ, and we who are on the Diskos will again become the Body of Christ, and then… We’ll say more about this later in this series.

The Liturgy of Preparation is completed. Now the Deacon or whoever else is available cuts up the remainder of the Prosphora, which during the Liturgy will be blessed and become the Antidoron / Ἀντίδωρον (“instead of the Bread”, pronounced “anTEEdoron”). This will be  distributed after Holy Communions. Originally it was intended for Orthodox who had not received the Eucharist. Now, for us who live in a multi-religlious society, it is usually available for all as a sign of fellowship and welcome.

distributed after Holy Communions. Originally it was intended for Orthodox who had not received the Eucharist. Now, for us who live in a multi-religlious society, it is usually available for all as a sign of fellowship and welcome.

The Priest now tends to any last minute preparations for the Divine Liturgy. At Saint Nicholas Church, Cedarburg, we now are ready to begin Orthros/Matins, and we’re still over an hour away from the beginning of the public Divine Liturgy.

How to prepare to receive the Eucharist

The presiding Priest obviously must receive Holy Communion at the Liturgy, so his required preparation is extensive. It begins with Vespers (or in the Slavic tradition, the Vigil) the evening before, then the service of Preparation, then Orthros/ Matins (or in the Slavic tradition one of monastic Hours) in the morning, as well as fasting and repentance, including Confession if needed. Some clergy also say Saturday evening Compline privately, as well as other prayers. For as Saint Paul wrote, “Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of sinning against the body and blood of the Lord.” I Corinthians 11:27

The same principle applies to all of us. Receiving in “an unworthy manner”, does not mean we must be morally perfect, of course – for in that case no one could ever receive the Eucharist except Christ and his blessed Mother! It means we must truly be repentant and seeking God and goodness.

How much preparation should Orthodox laypeople make? This has varied from time to time and place to place.

How much preparation should Orthodox laypeople make? This has varied from time to time and place to place.

In the early Church people (unless they were placed under a penitential discipline) normally received the Eucharist every Sunday. It is not clear how they prepared.

During the many centuries when people received Communion only a few times a year (and this is still true in many places), preparation has usually consisted of something like this: “Lenten” Fasting during the week or at least for a few days before, the sacrament of Confession and sometimes the sacrament of Holy Unction.

Now frequent Communions are common again, following the tradition of the early Church. In this case, people should receive the Eucharist, unless they are in unrepentant sin and have not confessed, preferrably using the sacrament of Confession. For all, fasting from food and drink from midnight before is definitely required. * Some (not enough…) find Saturday Vespers and Sunday Orthros (or the Monastic Hour) helpful.

- This is for a morning Liturgy. And as with all fasting rules, this may be adapted if necessary. When our Deacon John got old and began fainting during Liturgy, I told him “Have some breakfast, for heaven sake. Passing out during Liturgy or watching you pass out is not helpful to the spiritual life!” Now that I am old, I also have a little something to eat before Sunday Liturgy. And please note:

Children should fast only up to their ability. Parents, be gentle. Don’t make receiving the Eucharist an unhappy experience for them. And if they are infants, don’t force Communion into their wailing mouths. It’s ok for them to just receive a blessing till they are ready. God understands.

Children should fast only up to their ability. Parents, be gentle. Don’t make receiving the Eucharist an unhappy experience for them. And if they are infants, don’t force Communion into their wailing mouths. It’s ok for them to just receive a blessing till they are ready. God understands.

Those who cannot come to the services named above need to use some of the Church’s appointed prayers of Preparation for Communion, which can be found in almost any Orthodox prayer book. The Ancient Faith Prayer Book has an especially fine collection of them.

Also (and here we go again) those receiving the Holy Eucharist should be at Divine Liturgy more or less on time. Many Orthodox clergy today, trying to deal with reality, promote a (not canonical) rule that, barring emergency, if people want to receive Communion they should be at Liturgy no later than the reading of the Holy Gospel. Well, that’s better than nothing. I don’t think our clergy ever turn anyone * away from the Eucharist because they came in late. But really, folks…

* that is, Orthodox people in good standing

_____________________________________

When we resume this series in due time, we will look at: How to prepare yourself for Orthodox worship. Then the Divine Liturgy itself: the Pro-Anaphora, also called the the Liturgy of the Catechumens – and in some Christian traditions the Liturgy of the Word, although that is an inadequate title for it. We’ll come to that.

_____________________________________

But first, at this time of year most churches, Orthodox and otherwise, ask their people to think about giving for the next calendar year, so…

Next Week: The Poor Rich Farmer

Week after Next: We begin two articles about The Church’s Theology of Giving, which will include some radical words from the Fathers

In the Roman Rite, when the Deacon prepares the chalice, he says, “By the mystery of this water and wine, may we come to share in the divinity of Christ, who humbled himself to share in our humanity.”

It’s also a good talking point when explaining theosis to Catholics.