The Service of Preparation, Part One

No clever “catch line” to introduce this Post. The Divine Liturgy is too serious a matter for that. But “serious” doesn’t mean dull. I hope you’ll find this interesting, informative, even enlightening.

Why this series? Because we Orthodox have attended the Liturgy so many times that we can easily take it for granted, not think about it, let our minds wander while we’re in church. I hope that by learning more about it, we will better appreciate the Divine Liturgy for the truly wonderful and life-giving thing it is.

Introduction to The Divine Liturgy

This will be an odd way to begin – for what follows below was written not by an Orthodox theologian, but rather by a mid-20th century Benedictine monk of the Church of England. It was written from a Western “angle”, of course, where Masses traditionally were offered for “private” occasions, while our Liturgy is not. However, in another way we are not so dissimilar. At every Divine Liturgy we offer prayers specifically for many people and their needs, until finally “Thine own of thine own, we offer unto thee in behalf of all and for all.”

I have never found a piece of writing which more movingly expresses what keeping Christ’s command, “Do this for the remembrance of me”, has meant –

to classical Roman Catholics …and to Anglo-Catholics

…and to Anglo-Catholics

…and to us Eastern Orthodox.

From the monk Father Gregory Dix:

Was ever a command so obeyed? For century after century, spreading slowly to every continent and country and among every race on earth, this action has been done, in every conceivable circumstance, for every conceivable human need from infancy and before it to extreme old age and after it, from the pinnacles of human greatness to the refuge of fugitives in the caves and dens of the earth. Men have found no better thing than this to do for kings at their crowning and for criminals going to the scaffold; for armies in triumph or for a bride and bridegroom in a little country church; for the proclamation of a dogma or for a good crop of wheat; for the wisdom of the Parliament of a mighty nation or for a sick old woman afraid to die; for a schoolboy sitting an examination or for Columbus setting out to discover America; for the famine of whole provinces or for the soul of a dead lover; in thankfulness because my father did not die of pneumonia; for a village headman much tempted to return to fetich because the yams had failed; because the Turk was at the gates of Vienna; for the repentance of Margaret; for the settlement of a strike; for a son for a barren woman; for Captain so-and-so, wounded and prisoner-of-war; while the lions roared in the nearby amphitheatre; on the beach at Dunkirk; while the hiss of scythes in the thick June grass came faintly through the windows of the church; tremulously, by an old monk on the fiftieth anniversary of his vows; furtively, by an exiled bishop who had hewn timber all day in a prison camp near Murmansk; gorgeously, for the canonisation of S. Joan of Arc — one could fill many pages with the reasons why men have done this, and not tell a hundredth part of them. And best of all, week by week and month by month, on a hundred thousand successive Sundays, faithfully, unfailingly, across all the parishes of christendom, the pastors have done this just to [“make”] the holy people of God.

Was ever a command so obeyed? For century after century, spreading slowly to every continent and country and among every race on earth, this action has been done, in every conceivable circumstance, for every conceivable human need from infancy and before it to extreme old age and after it, from the pinnacles of human greatness to the refuge of fugitives in the caves and dens of the earth. Men have found no better thing than this to do for kings at their crowning and for criminals going to the scaffold; for armies in triumph or for a bride and bridegroom in a little country church; for the proclamation of a dogma or for a good crop of wheat; for the wisdom of the Parliament of a mighty nation or for a sick old woman afraid to die; for a schoolboy sitting an examination or for Columbus setting out to discover America; for the famine of whole provinces or for the soul of a dead lover; in thankfulness because my father did not die of pneumonia; for a village headman much tempted to return to fetich because the yams had failed; because the Turk was at the gates of Vienna; for the repentance of Margaret; for the settlement of a strike; for a son for a barren woman; for Captain so-and-so, wounded and prisoner-of-war; while the lions roared in the nearby amphitheatre; on the beach at Dunkirk; while the hiss of scythes in the thick June grass came faintly through the windows of the church; tremulously, by an old monk on the fiftieth anniversary of his vows; furtively, by an exiled bishop who had hewn timber all day in a prison camp near Murmansk; gorgeously, for the canonisation of S. Joan of Arc — one could fill many pages with the reasons why men have done this, and not tell a hundredth part of them. And best of all, week by week and month by month, on a hundred thousand successive Sundays, faithfully, unfailingly, across all the parishes of christendom, the pastors have done this just to [“make”] the holy people of God.

Yes. The Divine Liturgy is what connects us to our past, makes us what and who we are, leads us into what we shall be in the Kingdom of God – and above all unites us to our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ. The Divine Liturgy is what creates us.

In this series, we won’t say much about the origin and history of the Divine Liturgy. Rather we’ll just go through the Liturgy section by section and explore and explain the meaning of what we do now – Sunday by Sunday, feast day by feast day.

The Hidden Liturgy

How many of you have ever been present for the first part of the Divine Liturgy? I do not mean the three opening Antiphons – “Through the prayers of the Theotokos” and so on in the Greek/Antiochian tradition, “Bless the Lord, O my soul” and the rest, in the Slavic tradition. *

- Many Orthodox arrive so late they never even hear these. I’ll complain about this off and on as we go through this series… though I know it never does any good!

The first part of the Divine Liturgy, of which I speak, is the Service of Preparation. In this the presiding Priest (or Bishop) and other clergy prepare themselves and then the Holy Gifts for the rest of the Divine Liturgy. How many of you even know this service exists?

It takes place well before the beginning of the public D ivine Liturgy. Usually the church is empty. When properly done (say I), it should come even before Orthros/Matins in the Greek/Antiochian tradition (or the morning Office in the Slavic tradition) – though sometimes it is done during those services. This isn’t as complicated as it just sounded! Come sometime, and you’ll see what’s going on.

ivine Liturgy. Usually the church is empty. When properly done (say I), it should come even before Orthros/Matins in the Greek/Antiochian tradition (or the morning Office in the Slavic tradition) – though sometimes it is done during those services. This isn’t as complicated as it just sounded! Come sometime, and you’ll see what’s going on.

The Priest who will preside at that day’s Liturgy normally presides also at the Service of Preparation. Often the assisting clergy and sometimes acolytes also take part. Laypeople are welcome to be present but almost never are.

All this is why I’m calling this the Church’s “Hidden Liturgy”. It is in fact the first part of the Divine Liturgy itself. It’s a shame that it’s such a secret. I wish clergy would regularly explain it to people, for it makes clear the meaning of what will later happen during the Great Entrance and the blessing of the holy Bread and Wine.

And that’s what we’re about to do here – with many pictures, so that you can see for yourself that which you probably have never seen before.

The Preparation for the Divine Liturgy

I said above that we wouldn’t look much at history, but it is interesting that this is the most recent addition to the Divine Liturgy. “Recent” in latter day denominations may mean “20th century” or maybe Sunday before last – and sadly this is now the case even in the traditional Western churches, where modern revisions have nearly destroyed the sense of liturgical continuity. I mean “recent” in Orthodox terms: The Service of Preparation became a fixed part of the Liturgy probably by the 11th or 12th century – though it has roots that go back much earlier as part of the unwritten tradition.

The Preparation consists of 1 The Kairon (Preparatory Prayers), 2 The Vesting of the Clergy, and 3 The Proskomidia or Prosomia, the Preparation of the Holy Gifts (the bread and wine) for consecration.

1 The Kairon

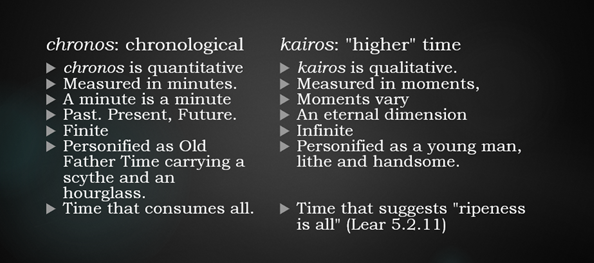

Kairon (καιρών) (Ke-ROHN) is one of the two ancient Greek words for “time”. “Chronos” (Χρόνος) means “clock time” – as in “What time is it?” “Kairos “ means the “appointed time” – as in “The time is at hand”. Why is the first part of this Liturgy of Preparation called “The Kairon”? Because now the time is at hand to begin our Liturgical journey beyond clock time into the eternal time of the Kingdom of God. *

“ means the “appointed time” – as in “The time is at hand”. Why is the first part of this Liturgy of Preparation called “The Kairon”? Because now the time is at hand to begin our Liturgical journey beyond clock time into the eternal time of the Kingdom of God. *

- Or as I’ve come to think, where clock time is transfigured into eternity. I know that at the Altar at Saint Nicholas I can see the clock in the sacristy during Divine Liturgy and I’m aware that the minutes are passing, but somehow at the same time, I’m also “somewhere else”, in another higher kind of time. I’m not describing this well. I don’t think I can.

Very likely this service was once introduced by the Deacon saying informally to the Priest, “Father, it is time to enter into the time of Liturgy”, or something like that – and the title “Kairon” stuck, though not within the text of the service. The Kairon begins with the Priest and Deacon standing before the Royal Doors, preparing to enter the Altar. Formally preparing – never mind that these days they probably just came out of the Altar through the side (Deacon’s) doors! In early times they emerged from a room off to the side and had not yet been in the Altar. Just so you know.

![]() The Priest (assisted by the Deacon) reverences in order the holy icons of our Lord, the Theotokos, Saint John the Baptist, and the patron saint of the church, saying certain prayers to each of them. Then they enter through the side Deacon’s Doors, not using the Royal Doors which are reserved for more solemn points in the Divine Liturgy.

The Priest (assisted by the Deacon) reverences in order the holy icons of our Lord, the Theotokos, Saint John the Baptist, and the patron saint of the church, saying certain prayers to each of them. Then they enter through the side Deacon’s Doors, not using the Royal Doors which are reserved for more solemn points in the Divine Liturgy.

They reverence and kiss the Holy Table and go into the sacristy or vesting room to put on their liturgical vestments.

2 The Vesting

We’re going to take some time with this, so prepare yourself. But really, has anybody else ever told you?

Why Vestments?

You Orthodox are accustomed to clergy vestments and probably take them for granted. But to the non-liturgical newcomer they look very odd, to put it mildly – men all arrayed in robes of lovely colors which are usually very elaborately  decorated. (A Subdeacon and I were once checking out color swatches for vestments and suddenly realized this is one of the few places in our society where guys can do that and not feel, uh…”strange”, shall we say?)

decorated. (A Subdeacon and I were once checking out color swatches for vestments and suddenly realized this is one of the few places in our society where guys can do that and not feel, uh…”strange”, shall we say?)

Orthodox clergy vestments derive from what men wore 2000 years ago when the Church was new. But why have we not kept up with the times? I mean, in most evangelical churches the pastors wear dress suits, and some of the more relevant clergy (or whatever they are) now even show up in blue jeans! Right: you thought I was kidding? Well, consider: British judges still wear 18th century wigs. American Supreme Court judges wear black robes. Why? Because these things exhibit tradition and continuity with the past. But have a revolution or Reformation and out they go. The Holy Orthodox Church has had no Reformations, no revolutions. Therefore our Orthodox vestments have not changed, and they visibly unite us to our origins in the ancient Church and with all the 2000 years of Orthodox history.

Right: you thought I was kidding? Well, consider: British judges still wear 18th century wigs. American Supreme Court judges wear black robes. Why? Because these things exhibit tradition and continuity with the past. But have a revolution or Reformation and out they go. The Holy Orthodox Church has had no Reformations, no revolutions. Therefore our Orthodox vestments have not changed, and they visibly unite us to our origins in the ancient Church and with all the 2000 years of Orthodox history.

Vestments, probably inadvertently, also came to serve another very practical purpose: They keep the individual Priest or Deacon or acolyte or altar boy from distracting people during the service. Instead of looking at the pastor and wondering why he’s wearing that ugly suit today – or blue jeans?! – or even if you happen to be upset with the Priest that day (and such things do happen), what you see at the Altar is just the “Priest” looking like every other Priest, and the Deacon looking like every other Deacon, and the squiggly altar boy looking like just all other squiggly altar boys. Therefore you may find it easier to concentrate on God instead of on the individual clergy and acolytes.

Over the years the clergy vestments also have taken on symbolic meanings, but that’s secondary and too much to go into now.

The Vestments

I said that our Orthodox vestments derive from men’s styles when the Church was young. The sticharion right  was the equivalent of our modern men’s pants and shirt sleeves. In the First Century, pants had not yet been invented, so a man sitting in the family room watching TV, so to speak, would wear something like this. But if he wanted to dress up and go to church, he would wear something like the phelonion

was the equivalent of our modern men’s pants and shirt sleeves. In the First Century, pants had not yet been invented, so a man sitting in the family room watching TV, so to speak, would wear something like this. But if he wanted to dress up and go to church, he would wear something like the phelonion  left, which is comparable to the modern man’s suitcoat. Of course men two millennia ago didn’t wear anything as fancy as our vestments. As with most things, clergy vestments got more elaborate as time went on.

left, which is comparable to the modern man’s suitcoat. Of course men two millennia ago didn’t wear anything as fancy as our vestments. As with most things, clergy vestments got more elaborate as time went on.

Bu the way, here I’m giving the terms we use in the Byzantine tradition. I think Slavic and other Orthodox may use other terms.

Over the Sticharion the Priest wears the Epitrachelion  – it’s a lot easier to use the Western term “stole”! right This is symbol of the Priesthood. For example, a Priest will wear this also when hearing Confessions or taking Holy Communion to the sick.

– it’s a lot easier to use the Western term “stole”! right This is symbol of the Priesthood. For example, a Priest will wear this also when hearing Confessions or taking Holy Communion to the sick.

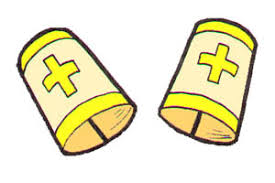

Epimanika  (shall we just say “cuffs”?) serve the practical use of keeping the sleeves from dragging.

(shall we just say “cuffs”?) serve the practical use of keeping the sleeves from dragging.

The Zone (ZO-ne) not pictured is a wide belt worn around the waist, which keeps the Epitrachelion tucked in.

The Epignation (e-pig-NAH-ti-on, which I hope you never have to pronounce) in Byzantine practice denotes that the Priest is authorized to hear Confessions. This seems to derive from the satchel once worn by Priests when they walked or rode from place to place to hear Confessions.

The Epignation (e-pig-NAH-ti-on, which I hope you never have to pronounce) in Byzantine practice denotes that the Priest is authorized to hear Confessions. This seems to derive from the satchel once worn by Priests when they walked or rode from place to place to hear Confessions.

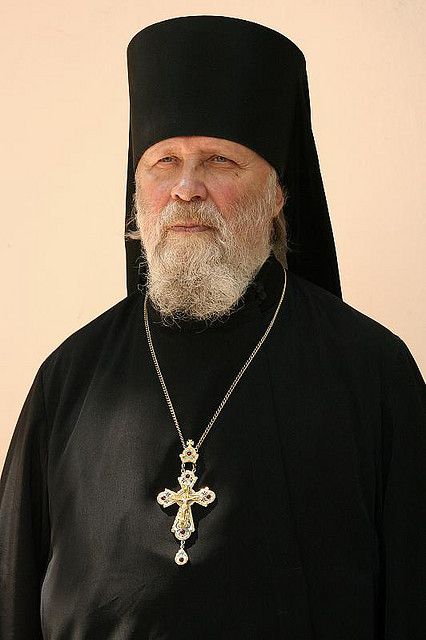

A large Pectoral Cross is worn by Priests authorized to do so, and the different traditions about this are so various that I’m even going to try… The head covering here indicates that the man is a bishop or a monk.

Also, some Priests wear hats in church.

Also, some Priests wear hats in church.

A Bishop wears a crown, similar to the Western mitre, and carries a staff, typically with two snakes at the top. You students of Scripture, please explain this for us. Why, you ask, does this Bishop not have a beard? Most clergy wear beards but they’re not required, not even of Bishops.

We are at last finished with vestments. Sometimes I think blue jeans would be simpler! However, since we’re not going to do that, and since you see these vestments all the time, I wanted you to know what you’re looking at.

Now, moving on…

Liturgical Colors

Over the centuries the colors of the vestments became associated with the liturgical seasons, as they developed. So far as I know, we Orthodox have no canon law about which season or day gets which color. But here, I think, is the usual pattern.

The finest white or gold: Pascha season. Gold: Other feasts. Red: Advent * and Martyrs. Blue: Feasts of the Theotokos. Green: Pentecost and its season. Violet: Great Lent. Black: used in some places for funerals (but I object!)

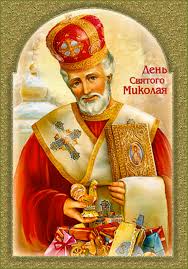

- Did you ever wonder why Santa Claus is always dressed in red and has a beard?

Here’s my theory: Saint Nicholas was an Orthodox bishop who died on December 6, during Advent, so is therefore always shown in red. Santa Claus, who “developed” out of Saint Nicholas, is therefore always in red. To the right and below is how I think this happened: classical St Nick icon, “sentimental” 19th century St Nick icon, 20th century Santa Claus. What do you think?

Here’s my theory: Saint Nicholas was an Orthodox bishop who died on December 6, during Advent, so is therefore always shown in red. Santa Claus, who “developed” out of Saint Nicholas, is therefore always in red. To the right and below is how I think this happened: classical St Nick icon, “sentimental” 19th century St Nick icon, 20th century Santa Claus. What do you think?

The Priest’s vesting doesn’t take half as long as it’s taken you to read all this! So let’s proceed:

The Priest’s vesting doesn’t take half as long as it’s taken you to read all this! So let’s proceed:

The clergy then return to the Altar and after a symbolic washing of hands, they begin the most important part of the Preparation.

Next Week: The Preparation of the Holy Gifts, the  bread and wine for consecration

bread and wine for consecration

Week after Next: The Poor Rich Farmer

Bless, Father!

Could you make mention of the prayers the priest says as he puts on the various vestments? I love that part! And I am very aware of it since I have been to three hierarchical liturgies in the past two months!