Iconoclasm, the Seventh Council, and after that

According to the story, it was during the Iconoclastic controversy that the monk Stephen saw soldiers trampling on an icon. When he objected they told him it was ok: it was only a picture. So Stephen took an image of the Emperor on a coin and trampled on it. When the soldiers arrested him, Stephen explained to them that it was ok; it was only a picture. As a result every year on November 28 we celebrate the feast of Saint Stephen the New Martyr. The Emperor didn’t forbid images of himself, only of Christ and the saints. You get the picture?

In these two weeks we’re digging a bit deeper into the history and theology of iconography. Last week we looked at the origins of icons. Now we move ahead to the attempt to eliminate Orthodox iconography and their permanent restoration.

The Iconoclastic Controversy

No Ecumenical Council had dealt specifically with the theology of images – until the challenge of the Iconoclastic movement in the Eighth Century.

![]()

Iconoclast means “icon smasher”. In the year 726 Emperor Leo III the Isaurian began a systematic attack on the holy icons. Icons were removed from public places, taken out of churches and homes, mutilated, burned, destroyed in various ways – except for a few which people managed to hide away, or were preserved outside the Empire. Some in the Church went along with the Emperor, especially clergy who knew which side their bread was buttered on.

What caused the Iconoclastic movement? It’s not clear. Just as today, political or religious movements suddenly sweep the country or the world, many of them making radical changes, some seemingly making no sense at all. Why? Often it’s hard to say.

This is important to remember: Iconoclasm was chiefly a political – not a religious or theological – movement. Iconoclasts quoted the Second Commandment (see last week), but Iconoclasm was enforced by emperors who like most politicians (despite their pretenses) knew little about religion.

The best guess (0nly a guess): The Empire was then threatened by iconoclastic Muslims who were winning battle after battle. The Muslim Caliph Yezid had just ordered the removal of all icons and images within his dominions. So Emperor Leo came to the “obvious” conclusion: Get rid of the icons within his dominions and win more battles.

Iconoclasm was not a popular movement. As I said last week, imagine if the government wanted to destroy that icon which had long been passed down through your family or the icon in church * that has spoken so deeply to you.

- Do you know the dreadful story of how the American government treated the natives of the Aleutian Islands during World War II? They removed them from their villages, kept them in appalling living conditions, burnt down and vandalized their homes and churches, and destroyed centuries-old icons and other religious treasures. After years of debate, in 1988 the U.S. Congress offered apology and some limited restitution, but the icons were gone.

Those who understood Orthodox theology resisted. They saw that this was not just an argument about pictures but about the very nature of Christianity. Was “the Word made flesh”? Did He take on an image? Have we “beheld His glory”? Can He be pictured? Whether unintentionally or intentionally, the Iconoclasts were ultimately denying the Incarnation, the humanity of Christ. Monks and nuns and theologians who opposed Iconoclasm were jailed, exiled, some of them martyred.

In the end Iconoclasm became a war between Church and state. In the Byzantine synthesis bishops were to tend to the Faith, emperors to secular affairs. Emperor Justinian had defended Orthodoxy (perhaps even against his Empress!) and that was fine – but Iconoclastic emperors were now reaching beyond their proper sphere of influence by trying to change the Faith.

Defenders of the Holy Icons

Iconoclasm caused the Church’s theology of icons finally to be clearly thought through and spelled out. Saint Theodore of Studion Monastery in Constantinople got himself into much trouble because of writings things like this: “Because man is in the image and likeness of God, there is something divine about the act of painting an icon.” He also drew out the moral implications, about a thousand years before emancipation caught on in the Christian world: “You shalt possess no slave, neither for domestic service nor for the labor of the fields, for man is made in the image of God.”

Iconoclasm caused the Church’s theology of icons finally to be clearly thought through and spelled out. Saint Theodore of Studion Monastery in Constantinople got himself into much trouble because of writings things like this: “Because man is in the image and likeness of God, there is something divine about the act of painting an icon.” He also drew out the moral implications, about a thousand years before emancipation caught on in the Christian world: “You shalt possess no slave, neither for domestic service nor for the labor of the fields, for man is made in the image of God.”

The most eloquent defender of icons was John Mansour, later known as Saint John of  Damascus, who wrote from the safety of Muslim territory (note the turban), where the emperors couldn’t get him. A multi-talented man, John worked at first as secretary to the Caliph of Damascus who protected him! and no doubt enjoyed seeing him taunt his enemies in Constantinople. In one of his Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images Saint John wrote: “Of old the incorporeal and invisible God was not depicted at all, but now, since God has appeared in the flesh and dwelt among men, I make an icon of God since He has become visible. I do not venerate matter, but I venerate the Creator of matter, who for my sake has become material, who has been pleased to dwell in matter and has through matter effected my salvation. I shall not cease to honor matter, for it was through matter that my salvation came to pass. Do not insult matter, for it is not without honor; nothing is without honor that God has made.”

Damascus, who wrote from the safety of Muslim territory (note the turban), where the emperors couldn’t get him. A multi-talented man, John worked at first as secretary to the Caliph of Damascus who protected him! and no doubt enjoyed seeing him taunt his enemies in Constantinople. In one of his Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images Saint John wrote: “Of old the incorporeal and invisible God was not depicted at all, but now, since God has appeared in the flesh and dwelt among men, I make an icon of God since He has become visible. I do not venerate matter, but I venerate the Creator of matter, who for my sake has become material, who has been pleased to dwell in matter and has through matter effected my salvation. I shall not cease to honor matter, for it was through matter that my salvation came to pass. Do not insult matter, for it is not without honor; nothing is without honor that God has made.”

The Seventh Ecumenical Council

After 54 years of imperial persecution, in the year 780 the Empress Irene called a Council in Nicaea to deal with the issue – which came to be called the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

The Fathers made a distinction between veneration (προσκύνησις/prosKINisis) and worship (λαριία/ laTREIa). We worship God. We venerate saints and holy objects: icons, the Cross, the Gospel book, and all  worthy people.

worthy people.

Regarding icons the Fathers established these principles:

1 Icons are not idols, becausewe do not worship them. The power is not in the matter but in who icons point to, in who lies behind the images. Surely this is obvious. Who has ever worshiped wood or paint? I have a picture of my parents standing in honor on my dresser, not because of the paper and ink but because of my parents. Saint Basil the Great had written long before: “The honor given to the image passes on to the prototype that lies behind it”.

Saint Leontios of Jerusalem (d. 1261) would later write: “We do not bow down to the nature of wood, but we revere and bow down to Him who was crucified on the Cross…. When the two beams of the Cross are joined together I adore the figure because of Christ who was crucified on the Cross, but if the beams are separated, I throw them away and burn them.”

Furthermore icons are not false images forbidden by the Second Commandment. Icons are true images of Christ and the saints. They protect the Faith and worship of the true God.

2 The doctrinal significance of icons is that they proclaim the Incarnation. Therefore the Fathers of the Council decreed that not only are icons permissible but that it is essential to have them – for to reject them is to deny Christ’s humanity, his materiality.

3 Therefore the Fathers continued, “As the sacred and life-giving Cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be exhibited on the walls of churches, in homes and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere” to be revered by all who see them.

4 The Fathers made it clear that icons are not only teaching devices but also means of grace, points of contact with God and the saints. Modern theologian Nicholas Ouspensky wrote in The Meaning of Icons (page 30) that the Fathers of the Council “rejected [a proposal] to place veneration of icons [only] on a level with that of sacred vessels.” Instead “the icon is placed on a level with the Holy Scriptures and with the Cross, as one of the forms of revelation and knowledge of God… each alike is a reflection of the higher world.” Therefore in Orthodox churches the Gospel book and the icons are treated the same: we kiss them, cense them, reverence them.

Ouspensky continued: “The image like the Divine worship transmits the teachings of the Church and expresses the grace-given life of the sacred Tradition in the Church…. As the word of the Holy Scripture [conveys] an image, so the image also [conveys] a word.” As Saint Basil had written, “What the word transmits through the ear, the painting silently shows through the image, by these two means, mutually complementing one another.”

All this was implicit from the beginning in the Church and was the practice of the Church from the beginning. It just took the Iconoclastic controversy to cause the Fathers to spell out why and defend it.

The Restoration of the Holy Icons

Did the Seventh Ecumenical Council end the Iconoclastic controversy? No. In the Orthodox Church, councils settle nothing unless they are accepted by the Church (all of us), and this is what happened, eventually. Meanwhile in 815 a new iconoclast Emperor, Leo the Armenian, came to the throne, and for another 28 years imperial troops were busily destroying icons again.

Finally the Empress Theodora finished Iconoclasm once and for all. On the First Sunday of Lent 843, beginning with a procession into Aghia Sophia in Constantinople, the holy icons were restored to the Church and all places in the Empire. Each year ![]() on the First Sunday of Lent, Orthodox have a procession of icons and celebrate the continuing Triumph of Orthodoxy, which signifies the triumph in the Orthodox Church of our faith in Christ Incarnate. At the end the Synodikon of Orthodoxy issued by the Seventh Council is proclaimed:

on the First Sunday of Lent, Orthodox have a procession of icons and celebrate the continuing Triumph of Orthodoxy, which signifies the triumph in the Orthodox Church of our faith in Christ Incarnate. At the end the Synodikon of Orthodoxy issued by the Seventh Council is proclaimed:

As the prophets beheld, as the Apostles have taught, as the Church has received, as the teachers have dogmatized, as the Universe has agreed, as falsehood has been dissolved, as Wisdom has presented, as Christ awarded, thus we declare, thus we assert, thus we preach Christ our true God, and honor His saints in words, in writings, in thoughts, in sacrifices, in churches, in holy icons; on the one hand worshipping and reverencing Christ as God and Lord; and on the other hand honoring them as true servants of the same Lord of all and according them veneration. This is the Faith of the Apostles, this is the Faith of the Fathers, this is the Faith of the Orthodox, this is the Faith which has established the Universe.

And with that began a great flourishing of iconography in the Orthodox world which has never diminished.

Later Iconoclasm outside the Orthodox Church

An extreme form of Iconoclasm arose again with the Protestant Reformation, in some places even to the point of forbidding crosses in church – apparently in reaction to late medieval Roman Catholic superstitions. A limited form of it has appeared after Vatican II, with most images now removed from Roman Catholic churches. Only a few traditional Anglican and Roman Catholic churches have retained many images. Most Protestants now admit crosses in church. Lutherans have crucifixes. Most  Protestants, though they would never allow icons or statues in church, have long had no problem with images in stained glass windows, often portraying scenes out of the life of Christ for teaching purposes.

Protestants, though they would never allow icons or statues in church, have long had no problem with images in stained glass windows, often portraying scenes out of the life of Christ for teaching purposes.

Those of you who have “Bible church” friends or relatives know that some of them actually think we Orthodox worship images. As for those Protestants who say (incorrectly) that the Second Commandment forbids all images – as one former Southern Baptist woman, now Orthodox, said to a Baptist friend, “Honey, then throw out the teddy bears and the pictures of grandma!”

Depictions of God the Father

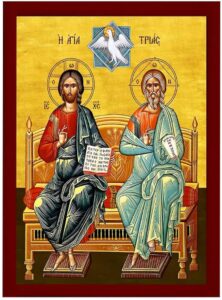

So far as I know there is only one latter-day Orthodox decree regarding icons, from the local Synod of Moscow in 1667 which forbade icons depicting God the Father as an old man, which He is not.

In such icons, sometimes the eternal Father is shown as older than the eternal Son, which He is not – suggesting Arianism –with the Son seated beside the Father and the Holy Spirit depicted as an impersonal dove between the two, suggesting the incorrect Roman Catholic doctrine that the Spirit proceeds “from the Father and the Son”, and perhaps is only the “love” uniting the Two. The decree of the Council did not stop this misuse, which can still be found to this day, especially in some late Nineteenth Century icons.

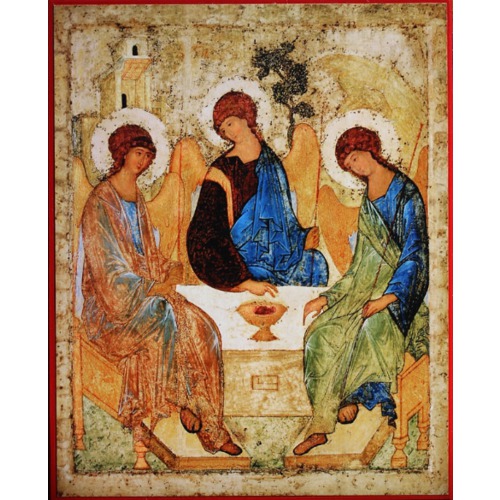

What is permissible is the symbolic depiction of the Holy Trinity in the form of the three angels (“men?”, “the Lord?”) who visited Abraham and Sarah. Note how the Son (in the middle) and Spirit (to the right) both incline towards the Father – all three of whom are the same “age”, so the speak.

Icons versus Statues versus nothing at all

The Seventh Ecumenical Council ruled that images are required, not specifying whether icons or statues. I know of no official explanation of why Orthodox do not have statues. It just is. I think it may derive from our understanding of icons as “windows into heaven”.In devotions, it’s easy to focus on three-dimensional statues as an end in themselves.

Two-dimensional icons are windows into which we can more easily enter and pass through into the Kingdom of Heaven on the other side. Look for a while at the image above for a little while and see if you are not drawn into it, into Him.

Long ago by chance one evening I walked into a little Roman Catholic Church on a side street in Manhattan which had shrines and candles and was filled with people. I don’t think I’ve ever felt a place so alive. I wonder what it looks like now, after recent Roman Catholic “reforms”.

The big problem with the elimination of images in many contemporary churches – non-Orthodox, that is – is this: Without images, religion easily tends to become solely intellectual, theological, impersonal.

But walk into any Orthodox Church… Not to brag but take, for example, our Saint Nicholas Church, Cedarburg, Wisconsin. This was formerly a Protestant building, as you can tell by the arched windows by the side.

![]()

Or an example at Sunday Divine Liturgy: Saint Sophia Greek Orthodox Church, New London, Connecticut. Feel how alive it is.

The Orthodox Church is about persons, holy people in our images, people standing beside us in church, in the Church, all of us united with Him Who out of His incalculable love came to earth in Person to save us.

And that’s what our holy icons are all about. A Methodist bishop said it some years ago – a great oversimplification, certainly, but it points to the truth: “The Protestant church is the church of faith. The Roman Catholic Church is the church of obedience. The Orthodox Church is the church of love.”

Enough said.

Next Week: “I believe. Help my unbelief.”

Week after Next: Saint Mary of Egypt