The Hidden Purpose of Holy Icons

Did you ever watch a classic iconographer paint (write *) an icon?

![]() * “γράφω” (grapho): “write”

* “γράφω” (grapho): “write”

This requires many layers of egg tempura paint, each properly prayed over. The iconographer begins with a plain board, correctly shaped and prepared. (I’m omitting much of the process here.) Along the way a layer of clay earth tone is used, then later white on which the outline of the person is sketched. After this come layer after layer after layer of various colors, each requiring much time to dry. In this lengthy process the full image of the person portrayed gradually emerges, finally possessing almost a three dimensional quality. This is impossible to show on the internet, but the image below gives you some idea.

Sometimes “inverse perspective” is used to draw us in, so that things get larger rather than smaller in the background. Look closely:

Ornamentation is often placed on the garments and the “context” shown around the figure. At the end radiant gold leaf is applied to the halo and sometimes even surrounds the person portrayed.

The “hidden purpose” is this: That is how God is creating mankind. (As you know, the Greek word εἰκών means both “image” and “icon”, and I’ll use the terms interchangeably here.) Over long aeons (“days”, in Genesis) God prepared the “board” for us, finally forming us out of the clay. He made man and woman in “His image and likeness” His goal is that finally, as Saint John wrote, “we will be like Him” I John 1:2– not as He is in His essence but “like Him”. Many theologians have distinguished between God’s “image” in which we were made, and God’s “likeness” which we can become. In any event, our icons (yours and mine) are far from completed, scarcely more than the first sketches – and those we have defaced with some help from Down Below.

(Might God be making other icons of Himself in other parts of His cosmos? Interesting question, which is unanswerable. Thus far. )

These next two sections. will be an attempt at historical theology (theological history?). Don’t be scared off. This is interesting – at least I think so. We’ll look more closely into what lies behind the Church’s use of icons. New readers: It will help if you read last week’s article before you read this one.

The Distorted Image

God is invisible, “who dwells in inaccessible light, whom no man can see or ever has seen.” I Timothy 6:16 He in His essence can never be portrayed as He is, for He is the Creator of images, who stands “outside” our material world. In His essence He has no physicality, no body – at least He didn’t until * His Incarnation in His Son Jesus Christ.

- That is, if we can speak of “before” and “after” in relationship to God, which we can’t.

Long before the coming  of Christ our God, there was already a sort of “primitive” icon of God: mankind, created in the image of God, in our Edenic pre-fallen state. Then we were like an early sketch of the figure on an icon. Many “layers” were still to be added.

of Christ our God, there was already a sort of “primitive” icon of God: mankind, created in the image of God, in our Edenic pre-fallen state. Then we were like an early sketch of the figure on an icon. Many “layers” were still to be added.

But by the time mankind had the ability to make portraits, our human images were not only incomplete but defaced. Mankind has fallen from grace. What remained of our image of God? Quite a lot, actually. Like God we can still think, plan, imagine, create (in a limited sense), and most important we still have the potential for eternal life. But we are now like a dirty icon. Tthe image of God in you and me has been scruffed up, stained, soiled, distorted, sometimes almost unrecognizable. An “enemy” has come into God’s icon studio and has done this, and we don’t know how to clean ourselves up. So the completing of our human icons had to wait until the coming of Christ, the Sinless One, the perfect image of God.

There are moral implications to this which we should never overlook. All men and women in this fallen world are still icons of God, albeit imperfect ones. If you came across ![]() a defaced icon would you still reverence it? Then honor people, honor the image of God in people, even the worst of them. Icons can be cleaned up, restored, completed. All persons have the potential someday to become beautiful holy images again. Don’t deface them even further! Don’t deface yourself even further.

a defaced icon would you still reverence it? Then honor people, honor the image of God in people, even the worst of them. Icons can be cleaned up, restored, completed. All persons have the potential someday to become beautiful holy images again. Don’t deface them even further! Don’t deface yourself even further.

The Second Commandment

What exactly did Exodus 20:4 forbid? Did it forbid the use of images in worship? Read closely: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; you shall not bow down to them or serve (worship) them”.

The prohibition was on making images of false gods, idols, and worshipping them. * Pagans had images of gods, “fallen” gods, not the one true God, the Creator of heaven and earth. Some of these were demonic. Even the best of them were “misdirected” – for example, the statues of Greek gods and goddesses which substituted idealized physical beauty for the true spiritual image of God.

- If it’s interpreted in any other way, then it forbids the use of all images: out with our pictures of grandma! out with our kids’ teddy bears! and our televisions and computers!

Were all images forbidden in Jewish places of worship? No.  Exodus 25:18ff gave directions for the adornments to surround the Ark of the Covenant: “And you shall make two cherubim of gold, of hammered work shall you make them, on the two ends of the mercy seat… The cherubim shall spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings… and you shall put the mercy seat on the top of the Ark…” This was acceptable, just so long as no one “worshipped them” as if they were gods. A few

Exodus 25:18ff gave directions for the adornments to surround the Ark of the Covenant: “And you shall make two cherubim of gold, of hammered work shall you make them, on the two ends of the mercy seat… The cherubim shall spread out their wings above, overshadowing the mercy seat with their wings… and you shall put the mercy seat on the top of the Ark…” This was acceptable, just so long as no one “worshipped them” as if they were gods. A few  synagogs, both ancient and modern, apparently have contained murals of other figures. See, for example: https://smarthistory.org/synagogue-dura-europos/

synagogs, both ancient and modern, apparently have contained murals of other figures. See, for example: https://smarthistory.org/synagogue-dura-europos/

Why the Old Testament hesitation about images in worship? Because God was carefully shaping the Jews into a people who, long before any other nation, knew to the depths of their being that there is only one true God, who dwelt beyond any imagery. We Christians say this was the preparation for the coming of Jesus Christ in “the fullness of time”. So that a few Jews at least would recognize that this one Man, if He was indeed divine, must be the One True God in the flesh. At the time no other peoples could have grasped this; they would have turned Jesus into just one more god among many.

Then with this knowledge fully established in the earliest Christians, the Church could move out into the pagan world with the clear message that the one true God, the Maker of heaven and earth, “for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, and was made Man”.

The Development of Christian Iconography

God has taken on a perfect human icon in Jesus Christ, the Sinless One. That which we lost in Eden is restored in Jesus Christ. In this perfect Man, God can now be imaged *, and in Him the process of restoring and completing the icons of you and me has begun.

“The invisible God can now be seen.” This seems paradoxical. We can only go with what the Lord Himself said and with the words of the Scriptures. For example, “Philip said to Him, ‘Lord show us the Father’… Jesus said to him, ‘Have I been with you so long, Philip, and yet you do not know Me? He who has seen Me has seen the Father.’”John 14:8-9 (See last week’s Post for some other texts.)

So from earliest times Christians had images, icons, without causing much controversy. The theology behind this was not yet  spelled out. This is generally the case in Orthodoxy: We don’t define matters carefully until they’re challenged, because putting things into words, while it may become necessary, is often limiting, inadequate, misleading.There is still much in the Orthodox Tradition that has not been carefully explained. (At the present time, a number of matters in the Tradition are being challenged, and I wish our theologians would get to work exploring and explaining them.)

spelled out. This is generally the case in Orthodoxy: We don’t define matters carefully until they’re challenged, because putting things into words, while it may become necessary, is often limiting, inadequate, misleading.There is still much in the Orthodox Tradition that has not been carefully explained. (At the present time, a number of matters in the Tradition are being challenged, and I wish our theologians would get to work exploring and explaining them.)

I wrote last week of the traditions about the Icon Not Made With Hands, and about Saint Luke the Evangelist making the first icons of the Theotokos. There must be some explanation as to why from earliest times the images of Christ and His Mother and even Saints Peter and Paul have been essentially the same. * There must have been a single common source, otherwise there would have been a multitude of imaginative images of them – since the ancient Church had no ability to control what icons should look like.

- A few other images of Christ have been found from the early Church – in the catacombs, for example, as a young Good Shepherd surrounded by sheep, but these were obviously symbolic. I mean, nobody believed that He really ministered to sheep! Why did they depict Him only in symbols? Probably for reasons of safety, since it was dangerous to be a Christian.

Because most ancient Christian images were later destroyed by the Iconoclasts, we know little about them. A few have been preserved at Saint Catherine’s Abbey at Mount Sinai which was outside the Empire and never hit by the Iconoclasts. These are ![]() in the same general tradition which continues today. One of Christ the Savior right from the Sixth Century is remarkable, with one eye said to show his compassion, the other his judgment.

in the same general tradition which continues today. One of Christ the Savior right from the Sixth Century is remarkable, with one eye said to show his compassion, the other his judgment.

Another reason why Iconography is not contrary to the Second Commandment?

With the coming of Christ, the Old Testament Law has been turned upside down, or rather fulfilled. (“I came not to destroy the Law but to fulfill it.” Matthew 5:17). God has taken on a human image, and so images of him can safely be used in worship. As for why we have icons of his saints, let’s wait and let the Seventh Council explain that next week.

The Apostolic Council of Jerusalem Acts 5 dealt specifically with whether the Old Testament Law is still in effect. The decision was this: “The apostles, the presbyters and the brethren, to the brethren who are of the Gentiles in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia:… [Some have been telling you] you must be circumcised and keep the law – to whom we gave no such commandment”. The Council decided “that you abstain from things offered to idols, from blood *, from things strangled *, and from sexual immorality” . Nothing was said about not making images – or even the rest of the Ten Commandments!

- which were deeply offensive to Jewish Christians

The Commandment forbids imaging and worshiping false gods. But Christ is the True God.

Was Iconography derived from Paganism?

The answer is Yes, but No.

Some in the early Church were suspicious of images for fear of Christianity getting confused with pagan idol worship. However Eusebius in his Fourth Century Church History wrote, “I have seen a great many portraits of the Savior and of Peter and of Paul, which have been preserved up to our times” – which suggests they go back to the beginning. He also mentioned a statue of Christ which he had seen in Caesarea Phillipi in Palestine, erected by the woman with an issue of blood who had been healed by the Savior. His noting these things is especially significant, because Eusebius was one of those who distrusted icons, fearing they were too pagan.

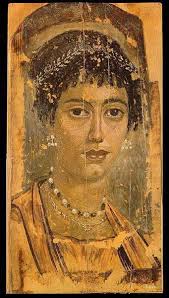

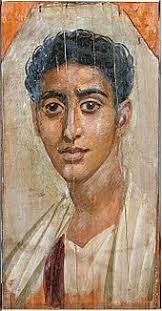

Did the Church’s style of iconography derive from paganism? Apparently so. It seems very similar to  Egyptian funerary art. Why was that not considered a problem?

Egyptian funerary art. Why was that not considered a problem?  Here again the theology wasn’t spelled out at the time. I think it just seemed acceptable, because Christ Himself had obviously drawn from pagan sources. There was nothing like the Holy Eucharist in Judaism, but certain pagan (even primitive) rites involved eating the body and blood of the god. Only pagan religions had dying and rising gods; yet Christ died and rose from the dead. After all, God created all the earth, and His image in mankind has never been erased. If Christ is God, then all things, not only Judaism, are His. So the Lord used certain acceptable things from His pagan religions, too. Following Him, the Church has carefully taken what was good in paganism and “baptized” it, so to speak, and used it in the service of the true God. That included iconographic style.

Here again the theology wasn’t spelled out at the time. I think it just seemed acceptable, because Christ Himself had obviously drawn from pagan sources. There was nothing like the Holy Eucharist in Judaism, but certain pagan (even primitive) rites involved eating the body and blood of the god. Only pagan religions had dying and rising gods; yet Christ died and rose from the dead. After all, God created all the earth, and His image in mankind has never been erased. If Christ is God, then all things, not only Judaism, are His. So the Lord used certain acceptable things from His pagan religions, too. Following Him, the Church has carefully taken what was good in paganism and “baptized” it, so to speak, and used it in the service of the true God. That included iconographic style.

Later Developments

During the Fourth and Fifth Centuries, Christian imagery became less symbolic and more realistic. This was because, after Constantine the Great, churches were filled with half-converted multitudes who didn’t easily grasp subtle Christian symbols, so there was need to portray Christ and the saints more directly. Also paganism was now less of a threat, so Christian “artists” were free to be more creative.

Particular icons now were used for theological purposes, to combat certain heresies. For example: 1 The image of Christ as a Man could counter what was left of Gnosticism and affirm what the Council of Chalcedon had said: that Christ is fully human. 2 To combat the Arian heresy and point to Christ’s divinity, the Alpha and Omega were added to His icon. 3 After the Council of Ephesus affirmed that Mary was Theotokos, Birth-giver of God, icons of the her with the Christ Child became more common.

The Council of Trullo

However, so far as I know, the first official Church directive regarding iconography did not come till the Council of Trullo (Quinisext Council) in 582, Rule 82: “Certain holy icons [which] have the image of a lamb” were forbidden “in order to make plain …for all eyes to see, if only by means of pictures, …that from henceforth icons should represent, instead of the Lamb of old, the human image of the Lamb, who has taken upon himself  the sins of the world, Christ our God, so that.. we may perceive the height of the abasement of God the Word and be led to remember His life in the flesh, His passion and death for our salvation and the ensuing redemption of the world.” For indeed, one of the central purposes of icons is to personalize our Faith, so that we come to enter into a loving relationship with Christ and the saints.

the sins of the world, Christ our God, so that.. we may perceive the height of the abasement of God the Word and be led to remember His life in the flesh, His passion and death for our salvation and the ensuing redemption of the world.” For indeed, one of the central purposes of icons is to personalize our Faith, so that we come to enter into a loving relationship with Christ and the saints.

The Council of Trullo also made clear that what is most important in the icon is the meaning which lies behind it, the glory of God and His Kingdom. Icons are on one hand portrayals of flesh and blood human beings, yet the portraits are stylized to point to the divine humanity of Christ, the divinized humanity of the saints, and heavenly truths expressed by earthly events.This implied that iconography had come to be used for teaching purposes, so that people could learn the life of Christ and the saints, and the meaning of those events.

Next Week: The Icon, Part Two – Iconoclasm, the 7th Council and what came after

Week after Next: “Lord I believe; help my unbelief.”