How’s that for a kicky title for a Blog Post? I hope you’re still reading.

That was the ponderous topic I was given to speak on at an Anglican-Orthodox conference at Nashotah House Episcopal Seminary here in Wisconsin, on October 9, 2009.

Prologue for Orthodox Readers…

…since, for the most part, I don’t know who all reads this blog.

Have you ever wondered exactly how our Orthodox Church manages to remain steady in the Faith in all ages, all cultures? Me, too, but I really hadn’t tried to figure it out before. This caused me to think! and I’d like to share my thoughts with you.

Nashotah is a lovely place, founded in the 1840s on the Wisconsin frontier. I think it’s the only Anglo-Catholic seminary left in the Western world.  People there are welcoming and well-spoken. Their worship is still “high church” Western rite and their doctrine as traditional as is possible, given the state of Anglicanism today. After all these years I still love the place. When I visit Nashotah I always feel torn

People there are welcoming and well-spoken. Their worship is still “high church” Western rite and their doctrine as traditional as is possible, given the state of Anglicanism today. After all these years I still love the place. When I visit Nashotah I always feel torn  – so grateful for how the Episcopal Church shaped me in the Faith, and at the same time so sad for what is almost lost now. Pray for the traditionalist Anglicans.

– so grateful for how the Episcopal Church shaped me in the Faith, and at the same time so sad for what is almost lost now. Pray for the traditionalist Anglicans.

Though there was a good Orthodox representation, the conference was attended chiefly by Anglicans. Its purpose was to try to resurrect something of the close relationship that once existed between Orthodox and Episcopalians, especially here in the formerly Anglo-Catholic central Midwest. As nearly as I can tell 9 years later, it didn’t work.

My task, as I saw it, was to show that the Orthodox Church knows the answer to the question posed above. In what follows here, I’ve revised the talk a bit for a more general audience, and also because I’ve thought of ways I could have said it better. If you’d rather skip the rest of this article, you can hear the original at: https://www.ancientfaith.com/specials/in_the_footsteps_of_tikhon_and_grafton/anglican_orthodox_enculturation

To begin:

Varieties of Church Unity

Different churches are held together in different ways.

1 Some, like the Anglicans, are organized by nation or region, all (in principle) in Communion with each other. They sometimes encompass many cultures. Doctrine and worship often reflect those cultures. Various parishes and dioceses may be “modernist” or “traditional” with many sub-variations, and they seem to be united in agreeing to disagree.

2 Roman Catholics have multi-cultural organizational unity under the authority of the Pope of Rome, with universal formal acceptance of fixed doctrine and worship. But at various times and in different places, you can never be quite sure what you’re going to find. I’ve seen everything from traditional Western rite to a “comedy club” wedding.

3 Each of the multitude of Protestant denominations has its own kind of unity with a huge variety of doctrines and polities, often reflecting their national or ethnic origin. Too much to go into here.

4 The Orthodox Church has a unique kind of unity which I’ll describe below. My point will be that Orthodoxy knows how to “teach” and maintain traditional Christianity despite our close unity with many cultures and ethnic groups. Since you invited me, a priest of the Orthodox Church, to speak on this topic I assume you want me to describe how we Orthodox do it. I don’t mean to sound “triumphalist”. I’m just describing what is.

The question here is about practice, so I’m not going to talk about the Faith itself or about theology, though these obviously lie behind and within all things in the Church.

Orthodoxy: “traditional Christianity”

35 years ago, before I was Orthodox, Father Tom Hopko (+ memory eternal), then at Saint Vladimir’s Seminary, told me that “in the Orthodox Church there is total theological unanimity”, and if I wanted to be a valiant defender of the Faith I should go somewhere else. I didn’t believe him. Now I do. For some years I kept peeking behind pillars thinking surely I could find a heretic somewhere. Plenty of sinners, but no heretics.

Get a bunch of Orthodox clergy together to debate theology, and there’s nothing to argue about. Each of us may emphasize different aspects of the Faith, but there’s no disagreement about what the Faith is. Even in lesser matters: for example, in 29 years here I have been asked twice why we don’t have female priests. Both times I gave a very nebulous answer (Orthodox theology about this is very undeveloped) and both times the people said, “Thank you for explaining it, father”, and went away apparently satisfied.

While I was still seeking, I visited a local Greek Orthodox priest and asked him, “What’s the difference between you and the Russians?” I assumed their very different ethnic backgrounds and histories would create theological differences. So “What’s the difference…?” He pulled out a Liturgy book and said, “At the beginning of the Liturgy, we use these antiphons, while they use those.” I asked, “What else?” He said, “That’s about it.”

Yes, that is “about it”. In every patriarchate, every archdiocese, every diocese, every parish, among all bishops and priests and theologians, in every nation, every culture, every ethnic group, the Orthodox Church is totally, completely, absolutely united in “traditional Christianity”. We call it simply The Tradition.

parish, among all bishops and priests and theologians, in every nation, every culture, every ethnic group, the Orthodox Church is totally, completely, absolutely united in “traditional Christianity”. We call it simply The Tradition.

Orthodoxy: pan-cultural

Our unity in The Tradition exists despite the fact that the Orthodox Church is multi-cultural, is in fact intentionally “ethnic”, closely identified with national, regional and ethnic cultures.

For many years, up till recently, Orthodox missionary work was almost impossible, and we’re just getting that act together again. But historically the Orthodox Church has tried to incorporate cultural traditions in order to make the Faith accessible to people in a way they can relate to. We’ve translated the Scriptures and Liturgy into the language of the people. Saint Cyril invented a written language, still used by Slavic peoples, who previously had none. We have ordained native clergy as soon as possible. We have incorporated whatever in local culture is compatible with the Faith. As Greece was converted long ago, the mountaintop shrines to the sun god Elios (Helios) became and still are chapels dedicated to the prophet Elias (Elijah), taken up into heaven.  Alaskan natives once honored their dead in pagan “spirit houses”. Now spirit houses have Orthodox crosses on or near them, where they pray for their dead.

Alaskan natives once honored their dead in pagan “spirit houses”. Now spirit houses have Orthodox crosses on or near them, where they pray for their dead.

Orthodoxy has wanted not only to convert individuals but also to build Orthodox Christian cultures. Take Greece again, which I know well because I visited there often in my better days. Though Orthodoxy is no longer the established Church, Greece remains about 95% Orthodox. I don’t know what percent of people are active in the Church, but most churches I’ve visited have been full on Sundays and feasts. With a population of 11 million, Greece has about 1000 monasteries, sketes and other monastic houses. You see icons in banks, post offices,  taxis. During Lent fasting foods are in groceries and restaurants. Orthros (Matins), Divine Liturgy and Vespers are daily on radio, and Sundays and festivals on television. During the 40 days of Pascha, even TV variety shows begin “χρήστος ανέστη!” “Christos anesti!” “Christ is risen!” Greek flags fly outside churches. In the old Orthodox lands, the Faith is so integrated with culture that folks sometimes find it hard to distinguish between the 2. This can be difficult for Orthodox people when they emigrate to non-Orthodox countries.

taxis. During Lent fasting foods are in groceries and restaurants. Orthros (Matins), Divine Liturgy and Vespers are daily on radio, and Sundays and festivals on television. During the 40 days of Pascha, even TV variety shows begin “χρήστος ανέστη!” “Christos anesti!” “Christ is risen!” Greek flags fly outside churches. In the old Orthodox lands, the Faith is so integrated with culture that folks sometimes find it hard to distinguish between the 2. This can be difficult for Orthodox people when they emigrate to non-Orthodox countries.

Here in the West the Orthodox Church is still organized according to Old World jurisdictions, multiple overlying episcopal and arch-episcopal structures – a mess from which the Holy Spirit will deliver us in his time. (Soon, please?) However, many of our members have been in America for 3 and 4 generations – and in Alaska much longer, thanks to the 18th century Russian mission – and all these folks are now very “Americanized”. We also have many American converts and many very recent Old World immigrants. Yet all the diverse Orthodox everywhere remain fully united in The Tradition. Orthodoxy’s integration with cultures has not compromised our commitment to traditional Christianity at all.

Orthodoxy: no top-down control of “traditional Christianity”

Is the Orthodox Church united in the Faith because of (Orthodox readers, try to stifle a giggle…) our superb well-organized system of top-down authority?

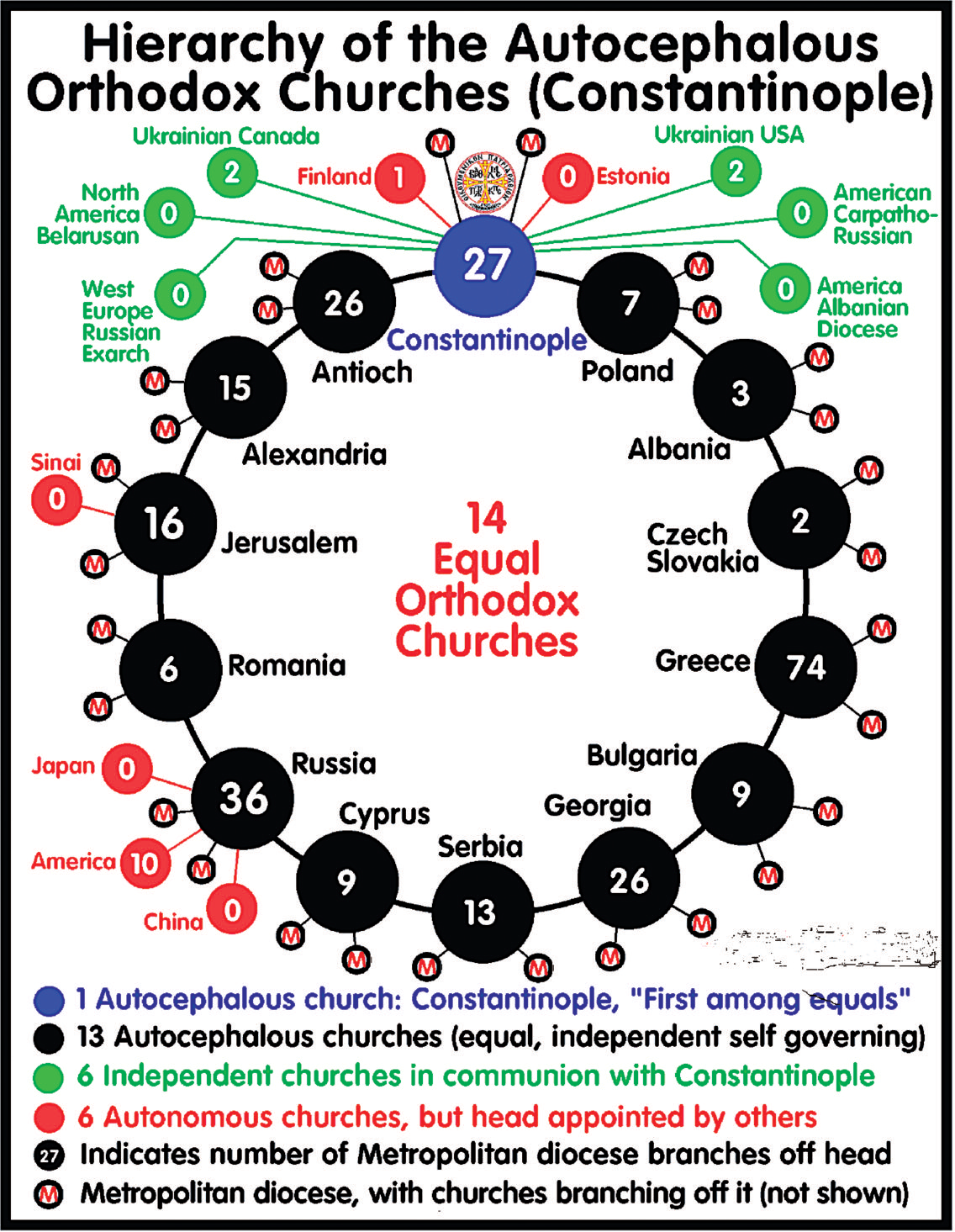

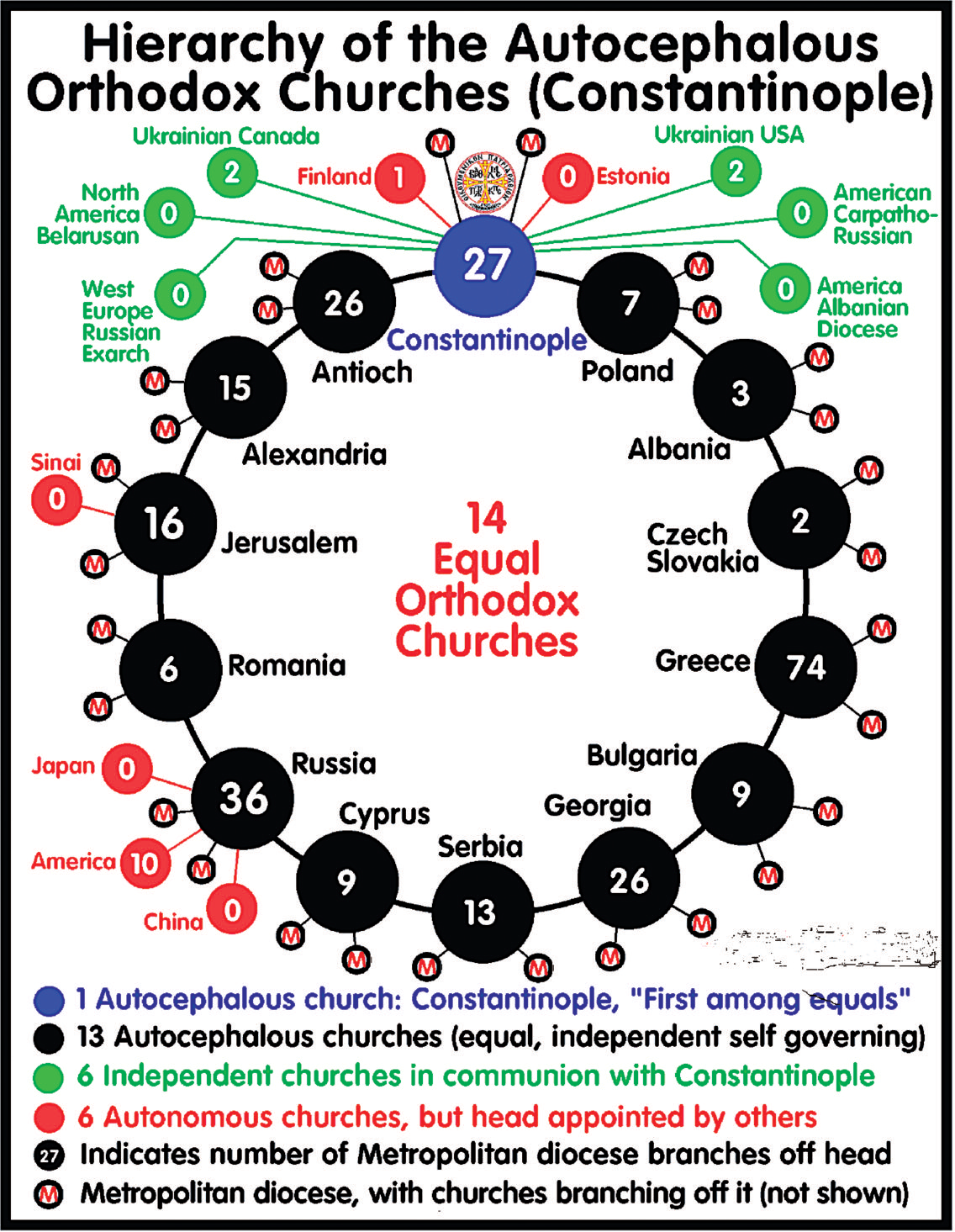

We do have an “internal control system” regarding the Faith, which I’ll talk about next week. But we have no one like the Pope of Rome with authority to “enforce” the Faith. Far from it. Most Orthodox would rebel with all their might against an “Orthodox pope” telling us what to do. We’re not big on external imposed authority. Our patriarchal and diocesan systems work well, but our Ecumenical Patriarch is “first among equals” and has no authority outside his own Patriarchate. When he recently called an “Ecumenical Council” to deal with organizational matters (there were no theological issues), most Orthodox bishops ignored it!

Constantinople and Russia disagree about whether one section of the former Russian Church in America (now called the Orthodox Church in America) is autocephalous. Confusing? Yes.

So how will we settle, for example, the current “dust-up” over the Ukraine between the Ecumenical Patriarch and the Patriarch of Moscow? God only knows. The New York Times called this worst Christian division since 1054. Wrong. We’re forever having “jurisdictional” disputes like this. No big deal. It will work out somehow. In principle the solution comes by “consensus”, and sometimes it actually does! For now, unless the patriarchs take to shooting at each other, few Orthodox (except Russian and Ukrainian nationalists) will pay much attention to the commotion. Why not? Because Russia and Constantinople have no disagreement whatsoever about the Faith. That’s what matters.

Don’t misunderstand. I’m not suggesting that all Orthodox are like robots walking in lockstep. Within the Orthodox Church there is plenty of room for different styles and approaches. In fact, contrary to outside appearance, there is a great sense of freedom within Orthodoxy – explain it as you will, and I won’t get into that now. Nor am I saying that all Orthodox are deeply “into” the Faith. Like any Church that has been around institutionally for 2 millennia, we have many folks who grew up in the Faith and just take it for granted. But it would not occur even to them that the Faith could be changed. Orthodoxy just “is”. Therefore the silly Question: “How many Orthodox does it take to change a light bulb?” Answer: “CHANGE?!?!”

Nor am I pretending that the Church has always been exactly as it is now. We all know that in the early centuries there was controversy as the Fathers argued about how to protect and express the Faith – the canon of the Scriptures, the Creed and so on. But in our eyes the purpose of this was not about how to define the Faith, but rather about how best to “put a fence around” the inexpressible Mystery of the Holy Trinity – to protect it from those like Arius, for example, who were trying to diminish its fullness. Forms of the Liturgy took somewhat longer to develop and become fixed, and we have always had very slow development in lesser practical matters. After that, in the 8th and 9th centuries there was a final major blow-up about imagery. In the 13th century some tried briefly and unsuccessfully to import Aristotelian philosophy into the Church. In the 17th century one of our Patriarchs developed Calvinistic tendencies, of all things, till the Turks took him out and drowned him. And that once again is “about it”. It has been 1200 years since the Orthodox Church’s last major theological controversy.

Orthodoxy: Pan-cultural Unity in “Traditional Christianity”

In the 2nd century Saint Ireneaus of Lyons described this unity which still exists today in the Holy Orthodox Church. To repeat, I’m not crowing, just describing.

“The Church, having received this preaching and this faith, although scattered throughout the whole world, yet, as  if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth. For, although the languages of the world are dissimilar, yet the import of the tradition is one and the same. For the Churches which have been planted in Germany do not believe or hand down anything different, nor do those in Spain, nor those in Gaul, nor those in the East, nor those in Egypt, nor those in Libya, nor those which have been established in the central regions of the world. But as the sun, that creature of God, is one and the same throughout the whole world, so also the preaching of the truth shines everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to a knowledge of the truth. Nor will any one of the rulers in the Churches, however highly gifted he may be in point of eloquence, teach doctrines different from these (for no one is greater than the Master); nor, on the other hand, will he who is deficient in power of expression inflict injury on the tradition. For the faith being ever one and the same, neither does one who is able at great length to discourse regarding it, make any addition to it, nor does one, who can say but little diminish it.” Against Heresies

if occupying but one house, carefully preserves it. She also believes these points [of doctrine] just as if she had but one soul, and one and the same heart, and she proclaims them, and teaches them, and hands them down, with perfect harmony, as if she possessed only one mouth. For, although the languages of the world are dissimilar, yet the import of the tradition is one and the same. For the Churches which have been planted in Germany do not believe or hand down anything different, nor do those in Spain, nor those in Gaul, nor those in the East, nor those in Egypt, nor those in Libya, nor those which have been established in the central regions of the world. But as the sun, that creature of God, is one and the same throughout the whole world, so also the preaching of the truth shines everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to a knowledge of the truth. Nor will any one of the rulers in the Churches, however highly gifted he may be in point of eloquence, teach doctrines different from these (for no one is greater than the Master); nor, on the other hand, will he who is deficient in power of expression inflict injury on the tradition. For the faith being ever one and the same, neither does one who is able at great length to discourse regarding it, make any addition to it, nor does one, who can say but little diminish it.” Against Heresies

Human nature being what it is, that doesn’t stop Orthodox people from arguing. (“Orthodox churches always have blue ceilings!” “What? I’ve never seen an Orthodox church with a blue ceiling!”) Just not about the Faith.

So, back to the original question: How do we “teach” the Faith to our people without selling out to culture? We think the better question is: “How do we form people in traditional Christianity?” I think Orthodoxy knows the answer.

We’ll get into that next week.

Week after next: It’s Hallowe’en! – DEMONS

Father,

I’m interested to see where you’ll go with this. From my personal experience, the Orthodox culture in America tends to fall into two categories: 1) a re-enactment of an idealized version of the old country, or 2) a pale variation thereof. I have nothing against experiencing and learning from cultures different from mine, but it does seem contrary to the Orthodox way when arriving in new countries. Not to mention discouraging for converts with no ethnic connection to traditionally Orthodox lands.

Yes, many Orthodox churches here are still in transition from Old World culture to Western culture, rather like Lutherans a hundred years ago. This process takes some time. A visitor who wanders into one of these may feel ill at ease – though I know of some who go out of their way to be welcoming. 50 years ago I was curious about Orthodoxy, visited a few parishes and thought, “You’ve got to born into this!” I know of someone who visited an Old World Orthodox parish and was interested, till the priest said, “We’ve been glad to have you visit. Now go back to your own people.” !!! However, things are changing. There are an increasing number of “Americanized” Orthodox churches. In some places they’re fairly common. In southeast Wisconsin we now have 5 or 6. In other areas they’re few and far between. In the next Post I’ll say a bit about how we in Cedarburg are trying to build a “midwestern ethnic” Orthodox church.

I’m curious, I know liturgically there is one Church, but regularly I read of the Western Captivity. And I see this “captivity” going three ways; Catholicism, Classical Protestantism, and liberal Protestantism. As a former Reformed Christian (conservative Presbyterian) sometimes I am frustrated with strains of thinking in Orthodoxy which seem to lean liberal Protestant in their approach to the Scriptures; the wholesale acceptance of German liberal Protestant criticism of the Bible, the uncritical acceptance of evolution – which may be because some don’t understand what evolution means, an evolutionary view of the theology of the O.T. where the Israelites were never true monotheists until the 3-5th century B.C., etc. How much should this trouble me? I’m often concerned, really bothered, that if Moses was not truly a monotheist, then how can we have an icon of Mary and Christ in the burning bush when Moses never would have understood his experience as an interaction with the One True God, but with a god among the gods. I could go on and on. Did Passover really happen, is the O.T. a-historical theologizing?

How prevalent is a liberal Protestant approach to the Scriptures in Orthodox seminaries? By no means am I advocating a Fundamentalist approach, that’s not it at all. I feel protected in whatever Orthodox Church I attend by the liturgy, but I feel as though these issues have consequences. What usually happens is that things get redefined. God’s wrath becomes nothing but the confusion of the OT due to an evolutionary view of the OT and God’s love/gentleness becomes the hermenutical rule for reading/redefining everything. I asked someone about the imprecatory prayers in the services and the person responded that the OT was really confused on who God was – then why place them in the liturgy and quote them endlessely in the N.T.? There are imprecatory like prayers in Revelation, “How long O Lord.” By now someone accuses me of wanting to believe in a wrathful God, or they accuse me of believing there is a “need” in God to judge, almost a sinful anger bound up that needs released, by no means! I want to believe that what the Holy Spirit has “spoken by the prophets” was actually spoken by Him, not a confused polytheistic, pagan understanding of God attributed to him (which smells of Marcionism to me, only by the way of liberal Protestant Biblical criticism).

So, while there is unanimity in dogma, I feel as if there is an undercurrent in Biblical studies, if properly examined, would undercut dogma, tradition, etc.

Sorry for a long post, but if you can comment a little I would appreciate it. I have few resources to address these questions.

There is no one Orthodox answer to this. I am no Old Testament scholar. I have only opinions formed by reading and thinking, but that’s all our Orthodox Biblical scholars have, too, regarding interpretation – though they know the Scriptures far better than I am. I think Orthodox theology won’t be much affected by the ephemeral opinions of some Biblical scholars, for the simple reason that the Orthodox Church is not founded on the Scriptures, as are Protestants. The Bible is our first witness to the Faith.

I don’t know much about Orthodox seminaries, since I was a latecomer to the Orthodox Church and came in through a side door. I’ve heard by the grapevine about one scholar who demythologized too many things, but I heard this from the “evangelical Orthodox” 30 years ago, who I felt had some fundamentalist tendencies because of their background. So…?

My belief, as it has developed, is that the Old Testament provides not a progressive “evolution” in the Jews’ understanding of God, but rather God’s progressive “revelation” of himself, which came to its fulfillment in Jesus Christ. Since then I think there has been progressive understanding of Him, as people come to see and appreciate different facets of The Jewel.

Monotheism seems to appear at least as early as Deuteronomy 6:4-5: “Hear, O Israel:The Lord our God, the Lord is one! You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength.” (NKJV) Who else has the right to demand such absolute devotion?

But the voice from the burning bush identifies himself only as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Joseph. Orthodox icons of Christ’s presence there (and even the Theotokos) obviously are a much later interpretation. The wording of the Ten Commandments allows room for other gods: “You shall have no other gods but me.” Jews and Christians later looked back and saw the one God revealing himself.

How to interpret the “imprecatory” prayers and admonitions of the Old Testament? They have troubled me for years. I still have no idea. Christ commanded us to love our enemies, which is contrary to the command to Joshua to wipe out everyone in Jericho. Did Joshua misunderstand? Has God changed his mind? I don’t know. Can any of our readers explain.

Did the prophets understand that there is one God? “There is no God apart from me” (Isaiah 45:21)

That’s about as far as my lack of wisdom goes. If anybody would like to correct me, please do.

Father Bill

I think the real confusion over gods and God is about what an Elohim is. Elohim refers to God, gods, angels, etc . – non human, non terrestrial beings, but God is an Elohim above all other Elohim, infinitely so because all other Elohim are created. When OT scholars look at the word used interchangeably, and since the word is often plural based on context, they assume polytheism instead of the ranks we Orthodox believe in. So there are gods, or created Elohim, but only one uncreated Elohim.

Fr. Stephen De Young is in the middle of some very helpful posts starting here https://blogs.ancientfaith.com/wholecounsel/2018/08/29/gods-divine-council/

I, for one, when thinking about imprecatory prayers – while I don’t know if they are valid for us to pray personally – must have some place because of their liturgical usage, especially around Pascha and after. Maybe they are projected against the demonic now instead of people? I remember Luther said something like Lord save sinners and restrain the rest. But I wonder if we have an anthropomorphic problem. We assume that if God is wrathful, vengeful, then it is analogical to our own sinful wrath – but if God is passionless this doesn’t work, but being passionless doesn’t mean there is no such thing as anger in God as if God cannot be affected, otherwise wouldn’t our whole Christology have to change? Because God is personal his anger must also be personal as is His love, but this is not a division within him – it would seem to me that His love is the same thing as His anger because loving one thing means excluding loving many others. In marriage we forsake all others. Loving some things means defending, upholding, protecting, what you love. Truly righteous anger is a product of love. But here again if we suppose God loves us in an accurately analogous manner to our selfish love – this will just get more confusing. Our love is often selfish, self-centered, that’s why Jesus gives no commendation to those who will love as the Gentiles. Is it possible to earnestly wish for the salvation of every man and still pray for their destruction (not damnation) if they do not repent, as in a time of war, I think so. Jesus weeps for Jerusalem and pronounces judgment, he wanted their peace but they would not have it. But to jump from there to an image of a rage-filled maniacal God who needs to get his anger out doesn’t work, Jesus is weeping, maybe balling his eyes out. That’s how I view judgment and imprecatory prayers – not that there is a ton of vaule iin my thoughts!

Free will and resposibility is constantly denied in our culture. Biology, physchology, are often completely deterministic. I am the way I am because of a ball that started rolling and I had no choice in the matter. When we take the view that people really don’t make choices out of their person, but rather are predestined to be the way they are, the reasonableness of judgement goes away and God just looks mean, vindictive – as He does toward the non-elect in Calvinism. Synergy, theosis are based on the notion that man has real participative capablity to work with God. If we uphold free will, we uphold responsibiilty, and therefore we uphold God as a weeping judge of mankind and as a rewarder, and as a rejoicer over the sinner who repents. To deny God as judge but to uphold him as rewarder, rejoicer, etc. – is to deny, for me at this moment in my life, that God is fully personal.

Thanks for your response!

As I said, I view all the early OT descriptions of God as part of his progressive revelation of himself. I think much of this was for a long time not comprehended fully by the Jews. I mean, it took the Greek philosophers till just before the time of Christ to figure out that there must be a single unifying power within the cosmos. How much harder then for that little tribe of uneducated Jews to grasp that there is one God outside our cosmos directing all things. Is the idea of the Elohim perhaps their first clouded glimpse (“through a glass darkly”) into the plural (Trititarian) nature of God? Just wondering. In all this I see no need to entirely reject pagan insights. C.S. Lewis wrote that the ancient myths prefigured Christ – their dying and rising gods, for example. Speaking of CSL, he also suggested in “Reflections on the Psalms” that one use for the imprecatory Psalms is that their words allow us to see the reactions – see into the terribly wounded hearts and minds – of those who have been unjustly mistreated. But I don’t think that explains everything.