Christ is risen!

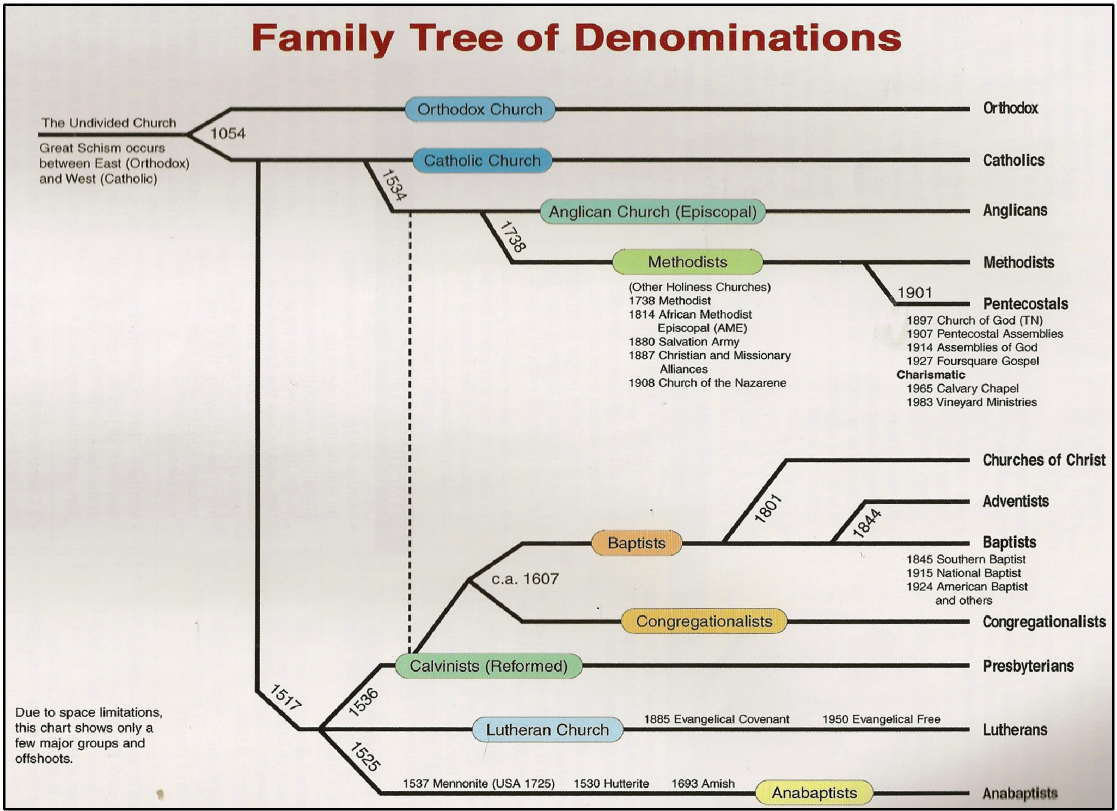

Luther wanted to reestablish Biblical truth, but because of his “Bible alone” principle, soon in Protestantism there was only a multitude of opinions about the Bible. And so Protestants were divided almost from the beginning.

Before Luther there was the Church, not many “churches”. Granted, Orthodox and Roman Catholics had a bit of a disagreement about which was the right Church! but  both were organically connected down through the centuries from the Apostles – as were also the Oriental Orthodox Churches, of whom we should talk sometime. But the earlier break-away organizations knew who they were; none dared called themselves “Church”. But after Luther and his followers were pushed out of the Roman Catholic Church, many independent groups of likeminded people began to get together, form new organizations and say “We are Church”.

both were organically connected down through the centuries from the Apostles – as were also the Oriental Orthodox Churches, of whom we should talk sometime. But the earlier break-away organizations knew who they were; none dared called themselves “Church”. But after Luther and his followers were pushed out of the Roman Catholic Church, many independent groups of likeminded people began to get together, form new organizations and say “We are Church”.

The Origins of the Denominations

The term “denomination” is usually defined as an “autonomous branch of Christianity”. However, just to make things clear, Orthodox look at the Orthodox Church not as one of the “denominations”, but rather as “the Church”.

Last week we considered the origins of Protestantism. Now we’ll look at the relatively few major denominations that came out of the first centuries of the Protestant movement. There are other smaller ones we won’t cover. Then in a few weeks we’ll look at the 19th and 20th century developments which led to the complete fragmentation of Protestantism.

As I said last time, this subject is very complex. Even though I came out of Protestantism I’ve had to do a lot of research trying to keep things straight. If I have made mistakes, please add a comment in the place provided at the end of this article.

Most early Protestant denominations (like similar independent groups ever since the early Church) were led by strong charismatic individuals, each a fallible human being with his own interpretation of the Bible and the Faith. Like any of us each had an incomplete grasp of the Faith. However they drew followers and formed new groups, and so there were many Protestant denominations, each with its own view of the Bible and the faith.

In the brief descriptions which follow I’m trying to describe only the distinguishing characteristics of each denomination, not all their doctrines. (For that, “Google” them.) Remember what I said in Part One, that with many groups these doctrines may change from time to time, and that individuals sometimes disagree with or even publicly challenge what their denomination teaches.

As we look at these groups, don’t forget that all are filled with good, sincere people who love God. Remember what one of my professors said: “Many people are better than their theology” – just as we Orthodox are worse than ours.

The Classical Protestant Denominations

Lutheranism as it spread in northern Europe developed separate national organizations with somewhat different theological  approaches: German, Swedish and so on. In America, these old-country national groups formed separate “synods” with distinct theological differences. Some of them finally merged so that today in the United states there are 3 major Lutheran denominations (Missouri Synod, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Wisconsin Synod) which disagree about how to interpret “Bible alone”. None of the 3 are in communion with the others. The ELCA has taken a liberal turn and is now in communion with the Episcopal Church. Honestly I can’t grasp the theological differences between Missouri and Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Synod teaches that the Pope is the Anti-Christ, and their members are not allowed to pray with other Lutherans, not even dinner table prayers. Some years ago when people still felt safe to pick up hitchhikers, I gave a ride to a student from our local Wisconsin Synod seminary, who informed me that “we are the church that believes Jesus Christ is our Lord and Savior.” I don’t understand.

approaches: German, Swedish and so on. In America, these old-country national groups formed separate “synods” with distinct theological differences. Some of them finally merged so that today in the United states there are 3 major Lutheran denominations (Missouri Synod, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and Wisconsin Synod) which disagree about how to interpret “Bible alone”. None of the 3 are in communion with the others. The ELCA has taken a liberal turn and is now in communion with the Episcopal Church. Honestly I can’t grasp the theological differences between Missouri and Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Synod teaches that the Pope is the Anti-Christ, and their members are not allowed to pray with other Lutherans, not even dinner table prayers. Some years ago when people still felt safe to pick up hitchhikers, I gave a ride to a student from our local Wisconsin Synod seminary, who informed me that “we are the church that believes Jesus Christ is our Lord and Savior.” I don’t understand.

Calvin and the Presbyterians. Still in Luther’s time, in Geneva John Calvin wrote his Institutes of Religion and created a highly  structured denomination which in many ways was orthodox. He stressed the absolute authority of God and misinterpreted a passage in Romans which says God predestined people for salvation. In context what Saint Paul meant was that God desires all to be saved, yet gives us free will to reject him and his love if we choose. Calvin misunderstood this to mean that God has “pre-decided” that some will go to heaven and apparently others to hell, and neither our faith nor our deeds have anything to do with it. A dreadful doctrine. It turned God into an arbitrary tyrant, not our Father “who so loved the world”, who “is good and loves mankind”. Calvin’s followers became the Reformed Church on the continent, and Presbyterians in Scotland and the United States. Most “Calvinists” now reject Predestination, Calvin’s central doctrine. In America a few who still believe it have formed a new denomination, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, which has no connection with our Eastern Orthodox Church.

structured denomination which in many ways was orthodox. He stressed the absolute authority of God and misinterpreted a passage in Romans which says God predestined people for salvation. In context what Saint Paul meant was that God desires all to be saved, yet gives us free will to reject him and his love if we choose. Calvin misunderstood this to mean that God has “pre-decided” that some will go to heaven and apparently others to hell, and neither our faith nor our deeds have anything to do with it. A dreadful doctrine. It turned God into an arbitrary tyrant, not our Father “who so loved the world”, who “is good and loves mankind”. Calvin’s followers became the Reformed Church on the continent, and Presbyterians in Scotland and the United States. Most “Calvinists” now reject Predestination, Calvin’s central doctrine. In America a few who still believe it have formed a new denomination, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, which has no connection with our Eastern Orthodox Church.

German Anabaptists, who had no single leader, believed that each man may interpret the Scriptures as he pleases, but agreed that the  Bible says only adults should be baptized. That seems to be the distinctive doctrine of modern Baptists who are numerous only in America where they dominate the south. They comprise about a third of American Protestants. Each Baptist congregation is autonomous but usually associates with a Baptist “convention”, according to their theological views. Don’t confuse the very conservative American Baptist Association USA with the quite liberal American Baptist Churches USA.

Bible says only adults should be baptized. That seems to be the distinctive doctrine of modern Baptists who are numerous only in America where they dominate the south. They comprise about a third of American Protestants. Each Baptist congregation is autonomous but usually associates with a Baptist “convention”, according to their theological views. Don’t confuse the very conservative American Baptist Association USA with the quite liberal American Baptist Churches USA.

Anglicanism. This is really complex. The English Reformation came about not for theological reasons but because King Henry VIII wanted a  new wife to bear him a male heir. The Pope for political reasons did not give him a divorce, so Henry broke with Rome and declared himself head of the Church of England, as English monarchs still are. However, Henry kept all else the same – Latin Mass, private Confession, celibate priests. After his death, following new monarchs, Calvinists took over, then Roman Catholics again. Finally for the sake of political unity, Queen Elizabeth I gave the Church of England (Anglican Church) as broad a base as possible, designed to hold together those from almost-Roman Catholic to almost-Calvinist views. Deist “liberals” (see below) were added later. Anglicanism, called the Episcopal Church in America, has ever since tried to hold these 3 “parties” together. This unstable balance tilts frequently, as I discovered for myself. 75 years ago Anglo-Catholics (like us Orthodox in many ways) were ascendant. Today, however, in North America rather hard-nosed liberals rule, resulting in the formation of some new conservative break-away Anglican denominations. Meanwhile Anglicans in Africa are chiefly Bible-oriented “evangelicals”. And in Britain, from what I can gather, liberals and evangelicals seem to be on top. Next…?

new wife to bear him a male heir. The Pope for political reasons did not give him a divorce, so Henry broke with Rome and declared himself head of the Church of England, as English monarchs still are. However, Henry kept all else the same – Latin Mass, private Confession, celibate priests. After his death, following new monarchs, Calvinists took over, then Roman Catholics again. Finally for the sake of political unity, Queen Elizabeth I gave the Church of England (Anglican Church) as broad a base as possible, designed to hold together those from almost-Roman Catholic to almost-Calvinist views. Deist “liberals” (see below) were added later. Anglicanism, called the Episcopal Church in America, has ever since tried to hold these 3 “parties” together. This unstable balance tilts frequently, as I discovered for myself. 75 years ago Anglo-Catholics (like us Orthodox in many ways) were ascendant. Today, however, in North America rather hard-nosed liberals rule, resulting in the formation of some new conservative break-away Anglican denominations. Meanwhile Anglicans in Africa are chiefly Bible-oriented “evangelicals”. And in Britain, from what I can gather, liberals and evangelicals seem to be on top. Next…?

Out of England came the following::

The very Calvinist Puritans. The sub-sect whom we Americans call  Pilgrims left England not because they wanted religious freedom for all, but because they felt the Church of England allowed too much religious freedom. In America the arch-conservative Puritans finally became the Congregational Church, which is now part of the United Church of Christ which is one of the most liberal denominations.

Pilgrims left England not because they wanted religious freedom for all, but because they felt the Church of England allowed too much religious freedom. In America the arch-conservative Puritans finally became the Congregational Church, which is now part of the United Church of Christ which is one of the most liberal denominations.

18th century Deists – not a separate denomination, but an intellectual movement – believed that God created the world, wound it up like a clock and for the most part lets it run on its own. No miracles please. Many of America’s founding fathers were Deists, and this approach lies behind America’s form of government. Thomas Jefferson rewrote the Gospels and made Jesus into a sort of 18th century philosopher. This was the first stage of liberal Protestantism with its belief that reason is the road to truth and that people when given freedom will discover and do the rational thing. (The truth is that sometimes they do and sometimes they don’t.)

Methodism. In the 18th century John Wesley, a Church of England priest, rediscovered that salvation is not by faith alone. It requires  growth in holiness, which he called “sanctification” – spiritual discipline, prayer, fasting, frequent Communions – much like Orthodoxy at its best, with our emphasis on “deification”. Those who followed his method were nick-named Methodists. Like Luther, Wesley did not intend to form a new denomination but somehow he did. In the United States Methodists formed a separate organization, elected their own “bishops”, forgot Wesley’s methods and and finally, for the most part, turned liberal.

growth in holiness, which he called “sanctification” – spiritual discipline, prayer, fasting, frequent Communions – much like Orthodoxy at its best, with our emphasis on “deification”. Those who followed his method were nick-named Methodists. Like Luther, Wesley did not intend to form a new denomination but somehow he did. In the United States Methodists formed a separate organization, elected their own “bishops”, forgot Wesley’s methods and and finally, for the most part, turned liberal.

There are also Quakers who reject outward forms of religion, Amish who try to keep living in the horse and buggy era, Adventists who for 150 years have believed the Second Coming is at hand, Seventh Day Adventists who believe the Bible forbids worship on Sundays – and more.

How should we Orthodox relate to Protestants?

1 Remember that Protestants are not our enemies, but rather our misguided step-children, once or several times removed. To repeat, they are good, sincere people, many of whom have a deep love for God. Within these breakaway groups we find much that came down from Orthodoxy. They all have greater or lesser continuity with apostolic Christianity. I mean, Baptists do believe in Jesus, don’t they? So when thinking of Protestants, try to get past the prejudice and the polemics – of which I’m afraid I have sometimes been guilty. Now that I have been Orthodox for 30 years, I look back and bless God for those who, though inadvertently, led me toward Orthodoxy – the Methodist professor who taught us the Creed, some holy Anglo-Catholics who formed me in the Faith and in true prayer and worship, Archbishop of Canterbury Michael Ramsey (of blessed memory – I pray for him every night), a holy man who was Orthodox in almost every way. And I grieve for all that has been lost there.

2 Are Protestants in error? Yes. But before even thinking about it, remember that we members of the Orthodox Church are in error in how we live our Faith. And then note that not all Protestants are the same. As C.S. Lewis pointed out, if the correct answer to a sum of numbers is 400, 398 is wrong but it’s a lot closer than 17. Some Protestants are very like us, others very different -and often even more different from each other! As someone said, it is as if each Protestant group took pieces out of an old mosaic, put them back together again creating a different image, and then said, “This is the same picture; it must be because we’re using the same old pieces.” But it isn’t.  Actually all these denominations have left out some of the pieces. They are partial, narrower than Orthodoxy. Some Protestants eliminate sacraments; most eliminate the apostolic ministry and saints. Liberals may leave out the divinity of Christ. Conservatives often think God can’t work outside their system. The clear evidence that these denominations are missing something is that they are unstable, forever changing, dividing, reforming. They know they haven’t got it right.

Actually all these denominations have left out some of the pieces. They are partial, narrower than Orthodoxy. Some Protestants eliminate sacraments; most eliminate the apostolic ministry and saints. Liberals may leave out the divinity of Christ. Conservatives often think God can’t work outside their system. The clear evidence that these denominations are missing something is that they are unstable, forever changing, dividing, reforming. They know they haven’t got it right.

3 In dealing with these denominations we should, above all, be sad for what they’re missing. It’s got to be so difficult without regular Communion or Confession or the Mother of God and the saints, or without the glory of true worship, or without Christ

entirely, and with their doctrines forever shifting, so that what was “true” yesterday is now false. It must be dreadful for some to believe that many of their friends or family are going to hell because they’re not “born again” or whatever. My wife once heard a conservative Lutheran professor say to a woman in whose family an infant had just died unbaptized, that “All who are not baptized go to hell.” Lord have mercy. But don’t condemn individual Protestants. Even if they’re unhappy with their denominations, often they remain because of friends and family there whom they love, or because they simply can’t imagine anything else. It took enormous courage and strength for our old Deacon John, at Saint Nicholas, Cedarburg, to leave his Anglican family heritage of many generations, and become Orthodox.

entirely, and with their doctrines forever shifting, so that what was “true” yesterday is now false. It must be dreadful for some to believe that many of their friends or family are going to hell because they’re not “born again” or whatever. My wife once heard a conservative Lutheran professor say to a woman in whose family an infant had just died unbaptized, that “All who are not baptized go to hell.” Lord have mercy. But don’t condemn individual Protestants. Even if they’re unhappy with their denominations, often they remain because of friends and family there whom they love, or because they simply can’t imagine anything else. It took enormous courage and strength for our old Deacon John, at Saint Nicholas, Cedarburg, to leave his Anglican family heritage of many generations, and become Orthodox.

4 Should we point out the errors of Protestants? Only if they ask and then very gently. Never argue. Nothing does more harm than sounding like arrogant know-it-alls. That may be entertaining (for some) on talk radio and TV or in politics, but in real life it drives good people away. A reserved Orthodox “air” of mystery goes a long way. Some Protestants will ask. They are seeking something deeper, more stable, the Church. How can we reach them? All we need to do is just be Orthodox. Live our faith and let it radiate as it has now for 2000 years. If it seems right, say a word about what Orthodoxy means to you, and invite them to come to church and see.

5 Don’t feel threatened by Protestant denominations, no matter how large they are. Don’t worry that they will overcome the Orthodox Church. Remember that our Orthodox Church and Orthodox Faith come down to us unchanged from Christ, the Apostles and the Fathers. It has stood the test of time. Don’t fall for new interpretations which have been invented only in recent times. Eventually these separated groups will either return to the Church as Father Peter Gillquist and his “Evangelical Orthodox” group did 30 years ago, or they’ll fade away as they always do. All the breakaway groups from the early Church – Arians, Montanists, Dualists, Docetists, Monarchians, Modalists, Sabellians, Valentinians, Novatians and a hundred others – some of them lasted for centuries. Arians were once the majority. But where are they today? You see. Orthodoxy has staying power. Orthodoxy just goes on and on and on, stable in the Apostolic and Catholic faith, “to the end of the age”,

5 Don’t feel threatened by Protestant denominations, no matter how large they are. Don’t worry that they will overcome the Orthodox Church. Remember that our Orthodox Church and Orthodox Faith come down to us unchanged from Christ, the Apostles and the Fathers. It has stood the test of time. Don’t fall for new interpretations which have been invented only in recent times. Eventually these separated groups will either return to the Church as Father Peter Gillquist and his “Evangelical Orthodox” group did 30 years ago, or they’ll fade away as they always do. All the breakaway groups from the early Church – Arians, Montanists, Dualists, Docetists, Monarchians, Modalists, Sabellians, Valentinians, Novatians and a hundred others – some of them lasted for centuries. Arians were once the majority. But where are they today? You see. Orthodoxy has staying power. Orthodoxy just goes on and on and on, stable in the Apostolic and Catholic faith, “to the end of the age”,

The Fragmentation of Protestantism

If you non-Protestants are confused by the multiplicity of denominations above… just wait.

Late in the 19th century, what little unity as remained in the Protestant movement shattered, and Protestantism became what it is today. So in the last segment of this series, in a few weeks, we’ll look at modern times and liberal Christianity, the social gospel, fundamentalists, “community” churches, charismatic churches, Bible churches, born-agains, Pentecostals, Unitarians, Mormons, modern evangelicals, Christian Scientists, Jehovah’s Witnesses and who knows what all? It’s labyrinthine. And we’ll try to figure out why many good people fall for… well, very peculiar doctrines.

Till then, thank God for the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Orthodox Church.

Next Week: begin “The Miracles of Saint Nicholas”

Is it absolutely correct to say that Orthodoxy is unchanged from the time of Christ and the Apostles? Its theological principles may be the same, but its practice does evolve over the centuries. The way I’ve come to understand that is through the analogy of blockchain. A bitcoin is unchanging, but it carries its transactional history with it, so it accumulates additional information over time. Protestants viewed those accretions as corruptions, but they should be viewed as natural growth as the environment changed around the Church and as the Church changed its environment. I wonder, though, what a 1st Century Christian would think if he were dropped into a 10th Century Hagia Sophia during Divine Liturgy.

Kevin, I missed something in one of your comments, which are very thoughtful by the way. Did Saint George kill a crocodile instead of a dragon? Be imaginative: The dragon is Satan (see the book of Revelation). The maiden whom he protected is the Church, the bride of Christ. Simple.

Of course. (slaps forehead) There was no mention of dragons in any of the liturgical material for St. George today (OC), so I should’ve suspected. When you considered that he was contesting during the reign of Diocletian, the last and probably worst persecutor, the Revelation parallel really works.

Excellent points, Kevin. If I implied that our current Liturgy is identical to the first century Liturgy, I didn’t mean to. Of course, it isn’t. I think my favorite line about this was Father Alexander Schmemann’s: “Orthodoxy changes only in order to remain the same.” I think this is the same as what you say. The first big change in Orthodoxy was the New Testament, written to preserve the apostolic way, as it does yet today. Well, so long as people don’t change its essential context: that the Church, the Christian community, came first.

The Liturgy certainly evolved, but what about beliefs regarding Mary’s dormition and intercessory status, the fasting seasons of the Church, or what transpires in the period after a professed Christian dies? I’ve been reading the apostolic fathers and haven’t come across any references to such things, yet. Ignatius and Clement more or less mimic the New Testament epistles and the Didache only refers to Wednesday and Friday fasting. Now, such things may have stayed within the “private” teaching of the Church and weren’t issues written about in epistles, or anything written about them during the centuries of persecution is long gone by now. Given the immediate problems the Church faced in the early centuries, elaborate discussions of such things would have been a luxury, yet there must have been some because it seems to appear quite developed by the 300s.

Kevin, pardon my delay in responding. (Weekend duties followed by a bout of the flu. Ugh.) The fact that devotion to the saints seemed to appear “quite suddenly” and without controversy indicates that it was accepted and taken for granted long before that time. In any event, I’d consider that anything in harmony with the 7 Ecumenical Councils was not a new development, just a clarification of the Faith. There are also many matters which are not “of the Faith” – fasting rules, for example.

Fr. Bill it may be worth mentioning a potential source of Wesley’s “sanctification”. Wesley claimed to have been ordained by an Orthodox Bishop, Erasmus of Arcadia, and there is some evidence that he had intended to be Orthodox. However the Praemunire Act (enforced through the 1960s) prevented growth of Apostolic faith in Britain at the time. Some scholars have noted similarity between the Orthodox approach to Theosis and Methodism’s notion of “Sanctification”. And some have speculated that his view on sanctification was shaped by Erasmus. I’m not a scholar and only learned of this recently. There is a little information on it here – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus_of_Arcadia

This is the first I’ve heard of this. But even if he did lay hands on Wesley, I don’t know what it means. Orthodox bishops do not have private power to run around ordaining “willy nilly”. Ordination is an act of the Church, and ordinands are required to adhere to the fullness of Orthodox doctrine and worship.

I think one of the real disconnects is a Protestant looks for all justification for a given belief in the New Testament – when so much, maybe most of it is in the Old Testament – and since they have been taught to see the Old Testament through a particular theological lens, they fail to read the Old Testament correctly. I used to think David, when speaking of his righteousness in the Psalms, was talking about the imputed righteousness of Christ! There is an excellent book called the Unseen Realm by Michael Heiser that did more to lead me to Orthodoxy than anyone else. He’s an Old Testament scholar who’s an evangelical of sorts but he gives an unfiltered look at the O.T. and it becomes clear that the Orthodox continued true to that lineage.

I really believe the answer to why Mary is appealed to for intercession is in the Old Testament (and not in Maccabees).

The intercession of the Mother of God in the Old Testament?! Intriguing, but I don’t understand. Matthew please tell us a bit more about this.