Saint Nicholas in May?

Because on May 9, 1087 Saint Nicholas arrived in Bari in southern Italy. Merchants from Bari had translated (moved) his body from his tomb in his home town, Myra of Lycia in Asia Minor. Well, actually they stole him. This seems to have been chiefly a business venture. Holy Nicholas would draw pilgrims – and money! and so he has ever since. But in the process they also rescued him from the Seljuk Turks who, unlike the earlier Saracens, had no respect for Christian holy sites – which, as you know, has been true with many of their successors to this day. Bari has been Nicholas’ resting place (if you can call it resting) ever since.

Incidentally, the Turkish government not long ago asked that the body of Saint Nicholas be returned to them. Good luck.

May 9 is now kept as a minor feast of Saint Nicholas by some Orthodox – not all, despite our devotion to him, perhaps because it feels as if the Roman Catholics captured him? No. Those were the days before the Great Schism, and Bari was then still Byzantine territory, though not for long.  And God only knows what would have happened to his relics had they remained in Myra. So I think May 9 is worth celebrating.

And God only knows what would have happened to his relics had they remained in Myra. So I think May 9 is worth celebrating.

Saint Nicholas has been treated well in Bari. They built San Nikola Basilica to the left in his honor. His body lies in the crypt below, and the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Bari generously permits an Orthodox chapel there just to the left of his tomb, where Divine Liturgy is served regularly. (I described my own pilgrimage there in Blog post 18.)

Anyway, that gives us an excuse to talk about our dear Saint Nicholas in May. But first let’s look at…

Miracles?

I was about to title this article “The Miracles of Saint Nicholas”, till I discovered (for the first time in my 79 years) that “miracle” is not a Biblical term. There are 4 Greek New Testament words for the wonderful works performed by Christ and his saints. σημεῖον (semeion) means “sign”. τέρατα (terata) means “wonder” or “marvel”. δύναμις (dunamis) means “force” or “power”. έργων (ergon) means “work”. That is why the Church titles him “Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker” (Θαυματουργός), from word “thavma”, another Greek word for “wonder”.

None of the 4 words suggest what people today usually mean by “miracle” – that is, a wonderful work performed by supernatural means, contrary to the laws of nature. The problem with this is that there are no laws of nature. This is obviously a figurative way of speaking. I mean really, am I to think that if I knock my coffee cup off the edge of the table beside me, it will debate whether or not to obey the “law” of gravity? “Hmm.. shall I behave myself and fall or shall I disobey and miraculously leap up into the air?” I don’t think so.

In the Scriptural understanding, my coffee cup heads for the floor because God pulls it down. God right this moment is causing lesser mass to be drawn to greater mass. Because all things exist, all things happen by the direct immediate action of God. The whole cosmos exists now because God now says “Be!” Otherwise all would cease to be. Most things in creation behave regularly, not because they are controlled by “laws” but because God chooses to do most things regularly. (At least on our level of experience. Apparently not so on some subatomic levels.) He could just as easily choose not to do so. (That would be rather disconcerting wouldn’t it? “What’s my coffee cup doing on the ceiling?” Or “Whoops! it has vanished again, and now how am I going to get my morning caffeine?”) If we can just recover that understanding and begin to see all things, whether ordinary or extraordinary, as immediate acts of God, all things will come alive to us in a new way.

Is it worth mentioning here that none of the above is contrary to science? Science just describes what happens. Theology tells what or rather Who lies behind it all. Forgive me for rambling on about science again. I have degrees in both meteorology and theology, and in my lifetime I’ve spent (wasted?) a lot of effort trying to convince people that true science and true religion are not opposed but are rather complementary. Both are of God, the “Maker of Heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.” I think that’s an important point to establish in our bizarre, irrational, “post-truth” contemporary world.

These wonderful events are signs to us that God and his saints can do mighty works of power that seem impossible, “super”natural but aren’t really. There is no such thing as “supernatural”. Miracles are just God working in his usual way but faster. God’s healing power is built into nature, as any doctor will tell you. In a healing “miracle” he just speeds up the natural process. Likewise God (with a little help from his friends) is forever multiplying grains of wheat and then changing them into bread. In the feeding of the 5000 the Lord saw hungry people and so hurried things along.

These signs point us into the Kingdom of God, show us what it is like, filled with wonder and love and power and fulfillment and healing beyond what we can imagine or dare hope for.

About a quarter of the Gospel accounts consist of these wonders, beginning with Christ’s Virgin Birth. He passed on to his saints the ability to share these signs and wonders – not by their own power, of course, but by “channeling” God’s love and power. Christian history to the present day is filled with such stories. Our Orthodox Church calendar has a whole category of saints titled “Wonderworkers”.

And that finally brings us to the subject at hand…

Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, Archbishop of Myra in Lycia

We’ll begin today with the stories from Nicholas’ lifetime and shortly thereafter. Then in the following 2 weeks we’ll proceed to what he was up to in medieval times, then finally conclude with some modern wonders of this blessed saint. We’ll omit much, but we’ll still have a lot to cover. Nicholas is one of those saints who have done their greatest work after their deaths. To say that Saint Nicholas has been busy is an understatement.

Nicholas was born late in the 3rd century in Asia Minor, probably in the town of Patara near the Mediterranean coast. It is said he was named after his Uncle Nicholas, who was Bishop there. He must have endured the Great Persecution at the beginning of the 4th century, when the Empire tried to eliminate Christianity. He became Bishop of Myra, a nearby seaport.

There is oddly no record of Bishop Nicholas attending the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea. Legend says it was because Nicholas became so agitated when Arius began to sing his anti-Incarnational songs (“There was a time when the Son was not”, etc.) that he ran up and punched him out, and got himself expelled from the Council. Perhaps. In any event, it makes for great Saint Nicholas Day church pageants!

It was remembered that Bishop Nicholas dearly loved his people, and his people loved him. Over the years he has become the Church’s archetype of the good pastor.

Saint Nicholas died about the year 343. We don’t know that for certain, but we do know the day, December 6, because holy men and women were (and are) commemorated at services held in their memory on the day of their death – and Saint Nicholas Day has been December 6 as far back as can see. To the right: the ruins of an early Saint Nicholas Church in Myra, modern Demre.

The Wonderful Works of Saint Nicholas

Can we document these early stories? No. Nicholas had no biographer as some early saints had. He left no writings. All we have is what people who loved him passed down by word of mouth. So far as we can tell they were first written down a couple of centuries after his death.

Do any of you tend to be skeptical about such stories? If so, good! There’s nothing more damaging to true religion than superstition. And we all know that stories can get amplified and refined over the years, so don’t take these for more than they are. But also don’t take these stories for less than they are. They tell us the character of Bishop Nicholas as his people remembered him, and the sort of wonderful things he did. And please note that we have similar documentable stories about 20th century Orthodox saints, which are every bit as startling as these ancient wonders of Saint Nicholas. (Even “bi-location”? Yes.) This makes the old accounts far more believable.

Here is some of what was told about the wonders done by Bishop Nicholas while he was on earth.

While he was perhaps still a priest, not yet a bishop, he was sailing to the Holy Land on pilgrimage. A great storm arose, and Father Nicholas by his prayers calmed the sea. Or did this happen after his death? or did it happen twice? For many icons of Nicholas show him twice – sometimes in the boat, sometimes in the sea, or sometimes even in the clouds above the ship – settling the sea. Saint Nicholas became the patron of seafarers.

Another story tells of 3 boys who had been murdered by an inn-keeper, who had stuffed their bodies in a pickle barrel. (Horrible crimes are not a modern invention.) Nicholas somehow found them and raised them to life again.

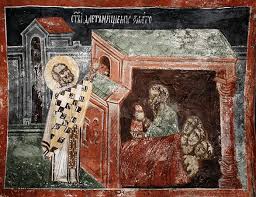

There is the well-known story about the 3 girls whose father was so poor that he couldn’t afford dowries. To survive they were going to have to become harlots. But as each came of age they would find a bag of gold on the living room floor. The third time he caught the donor, Bishop Nicholas.

There is the story of how there was a famine in the region, and the captain of a merchant ship carrying wheat on the Mediterranean was startled to see a man suddenly standing beside him, who begged him to sail his ship to Myra, and then he was gone. So the captain did so, and there was the same man waiting for him at the dock, who was, of course, Bishop Nicholas.

There’s the story of 3 military men from Myra who, out of jealousy, had been falsely accused of treason and were being held in prison awaiting execution. All attempts to free them had failed. The governor Ablabios (of whom we sing in  some of our Saint Nicholas hymns) refused. Until one night the Emperor Constantine awoke terrified to see a man standing beside his bed (or some accounts say it was a vivid dream), who identified himself as Bishop Nicholas of Myra and threatened the Emperor with hell-fire if he didn’t free the innocent men. Constantine checked it out, found the men were innocent and had them released.

some of our Saint Nicholas hymns) refused. Until one night the Emperor Constantine awoke terrified to see a man standing beside his bed (or some accounts say it was a vivid dream), who identified himself as Bishop Nicholas of Myra and threatened the Emperor with hell-fire if he didn’t free the innocent men. Constantine checked it out, found the men were innocent and had them released.

Bishop Nicholas was “like that”. These were only some of the stories passed down about Nicholas. Maybe even before his death he was called Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker.

Saint Nicholas the “Myrrh-streamer”

Bishop Nicholas died, and from his body there began to pour forth a clear sweet-smelling liquid which they called myrrh, for lack of knowing what else to call it. People turned it into a pun – Myrrh from Myra! There began to be many healing miracles.

The story about the myrrh might seem particularly hard to believe except for one thing: I’m getting ahead of the story, but the relics of Nicholas in Bari are still giving off this myrrh. Every year on the feasts of Saint Nicholas, December 6 and May 9, his coffin is opened, and a priest removes some of the myrrh. Since many, many pilgrims visit, over the centuries a whole cottage industry has grown up of making fancy bottles to hold the myrrh and sell it – at rather exorbitant prices, I might add. I know, I bought some… (I’m not going mention that at Saint Nektarios, they give away the oil .) At Saint Nicholas Church, Cedarburg, we use the myrrh for anointing on the feasts of Saint Nicholas and when special healing is needed.

Through this myth, there have been many healings through the centuries. None that I know of at our church, but then it’s hard to be sure what would have happened if the person hadn’t been anointed, isn’t it? Small relics of Bishop Nicholas’ body have been distributed all over the world, and we have one imbedded in our altar in Cedarburg. All these are our physical connections with the real flesh and blood and bone, myrrh-streaming Saint Nicholas of Myra the Wonderworker.

Next week: Wonders of Saint Nicholas through the centuries

In 2 weeks: Some Modern Wonders of Saint Nicholas

This “myrrh” exuding from bodies, and sometimes icons, is intriguing. I grew up Roman Catholic before going on walkabout through Protestantism and only heard of things like a bleeding or weeping crucifix or statue of Mary. Why is this a “thing” in Christianity? It’s not something that pops up here and there in the Old Testament. The Bronze Serpent was a healing “icon,” but it was purpose-built. The Ark of the Covenant did some odd things. I don’t know if there was any tradition of miraculous things related to the relics of the Prophets. The Orthodox universe is a little weird. Oozing relics, appearances of the Mother of God, icons that travel across seas or appear in trees…hardly a day goes by in the daily saints readings without my thinking, “Umm…okay, that’s…well, I guess you just had to be there.” It makes me wonder if the world isn’t more like Middle Earth than we thought. The West has really missed out on some things, apparently.

There is the vastly understated incident in 2 Kings 13:21 – “And it came to pass as they were burying a man, that behold, they saw a band [of Moabite raiders, per the previous verse], and they cast the man into the grave of Elisha: and as soon as he touched the bones of Elisha, he revived and stood up on his feet.” So we see the Holy Spirit working through the relics of Saints even in the Old Testament, which is amazing given the fact that it was several hundred years before the Christian Pentecost and the outpouring and indwelling on the Holy Spirit within the people of God.

Thanks Fr A. I had forgotten that. There’s also the story of Saul raising the ghost of Elijah (Elias) * from sheol with the help of a medium, but I don’t think we’d want to use that as a good example!

P.S. Sorry, I meant to say “Samuel”, of course. This is not an extra-double-super-supernatual pre-birth appearance of Elijah!

As to why, these are just signs to us that with Jesus Christ the Kingdom of God is now breaking through into our world. Am I right that Roman Catholics have more visions or appearances such as at Lourdes? Orthodox go more for tangible myrrh-bearing relics and weeping icons. As for tangible signs, I think Roman Catholics have more stigmata identifying with the suffering of Christ, while Orthodox saints tend to radiate light. However, such things are almost unheard of in the Protestant world, or even in the Anglo-Catholic tradition from which I came. Explain it all as you will. Anyway, once a person has seen a weeping icon or three, wonders become much easier to accept. The first weeping icon I saw, I watched the myrrh flow down from her eyes, then I peeked behind the icon screen to see if there were hoses attached back there. There were not.

Roman Catholics do have a lot of apparitions of Mary. They might be qualitatively different from Orthodox appearances, though. Stigmata didn’t appear in Orthodox lands and only appeared in the West after the Schism. I’ve heard it argued that the more emotional turn of Western ascetics after the pattern of Francis of Assisi brought people into a state where psychosomatic phenomena could manifest, whereas Orthodox asceticism expressly tries to avoid that kind of sensational outcome. I think many Protestants want this kind of thing, which explains all the charismatic shenanigans over the last hundred years, but there’s never been a foundation for it. There’s just a lot of power of suggestion and group hysteria.

I was thinking about why you don’t see much mention of Mary appearing in the first few centuries. The first “appearance” I can think of is in the dream the bishop had after deposing Saint Nicholas for smacking Arius. The first couple hundred years was the age of martyrs and I wonder if Mary kept a low profile so as not to diminish their glorious examples. Just a theory.

Interesting. I neglected to add before that, concerning some of the ancient saints’ stories passed down by word of mouth, one is allowed to be critical or circumspect. Sometimes they are obviously symbolic rather than literal. For example, a well-known Orthodox website, which shall remain nameless, used to inform us that Saint George killed an actual dragon that lived east of Beirut. Uh… Regarding the charismatic movement I would not be so critical. I was not drawn to it, quite the opposite. However, it led some into Orthodoxy, including several who have been leaders in our parish including our present pastor. Wherever we all have come from, we have found the fulfillment of it in Orthodoxy. When my wife and I arrived in England in 1992 on a mission to Anglican seekers, Father Michael Harper (+) and his wife Jean met us at the train. He, who was THE leader of the Church of England charismatic movement, said immediately, “We have been told we must be Orthodox. Tell us what it is.” (!) He became the very effective Dean of the Antiochian Deanery of Great Britain and Ireland.

From the perspective of one coming to Orthodoxy, how am I supposed to know what to take as real or as symbolic in the saints’ lives? Dragons, okay. That’s fairly easy. Maybe it was a nasty crocodile or something. Other things aren’t as clear. I don’t know the “code.”

I’m really sorry you asked me that question. I have no idea. My wife and I have gone back and forth on the subject. She (who is no pushover, believe me!) says just take the stories as they are and ride along. I’m more inclined to pick some of the more suspicious things apart and then have no idea what I’ve got. At the end I guess I’m content with seeing what the stories tell about the character of the saint. Does anyone else have ideas about this?

On a somewhat related topic, I just finished reading the Epistle of Barnabas this evening and I thought his allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament dietary laws was a load of nonsense. I can accept an allegorical reading of something, but not if it has erroneous descriptions of basic reality. His remark about rabbits growing new “orifices” every year was just laughable. The Church doesn’t equate the Fathers with Scripture, but it does give a lot of weight to their interpretations, so how do we deal with the occasional reading that leaves us facepalming? This is the first time I’ve encountered such a flight of fancy in the Fathers. Granted, I’ve barely begun. I hope Barnabas is just an outlier, but I wasn’t impressed by that epistle.

Kevin, you’re discovering that the Fathers are not infallible! Furthermore, the Orthodox Church does not tell us precisely when to take them seriously and when to ignore them (for example, when they speak of the habits of rabbits) or even which authors definitely are Fathers. The Orthodox Church does not function like a law court where everything is defined, or like a business enterprise where everything must be organized. We function like an old healthy family, guided by love and tradition. Things are defined and organized here only when necessary and sometimes not even then. It is hard for non-Orthodox to comprehend how we can “hang together” this way. It can be disorienting for converts who want things clearly laid out. However… it works. Hang in there. You’ll get the feel of it.

I get this. It’s actually a pretty ingenious form of security. You can’t break the system if there is no system. Rome made the mistake of building an elaborate machine and putting all authority in the hands of one human being. The Orthodox Church is, as Nassim Taleb might say, “anti-fragile.” It developed and refined its dogmas in response to stresses, rather than starting with a complex stack of theological principles that might turn out to be wrong or have to be modified.

I was reading something about the debate over which Greek New Testament text was “superior” as a base for English translations and was thinking, “This is such a Protestant problem.” If you have no authoritative Tradition and are sola scriptura, then you have to go chasing down the “original” text of Scripture. The early Church didn’t have a forensic interest in document preservation like we do in the modern era. It took quite a while to even put all of the NT books in one collection. If people in Greece had a slightly different reading than people in Alexandria, it was no big deal because the common Tradition made those differences unimportant.

Exactly. And if people wanted to attempt a major “reform” of Orthodox doctrine or worship, where would they start? With the Patriarch of Constantinople? A national Orthodox convention? A liturgical commission on high? The answer: None of the above. We don’t work that way. In any event, no one wants to do it. After 100 years on the continent, we can scarcely get regular Orthodox worship into English.