“Cardinal Humbert [of] the holy, primary, and apostolic see of Rome, to which the care of all the churches…pertains… [to] the glorious emperors, clergy, senate, and people of this city of Constantinople…I find great evil” [in this city… Therefore] know…that we thus subscribe the following anathema… unless they should repent. AMEN, AMEN, AMEN.”

Please remember again that what follows, like all history, is complex and subject to interpretation, and we’re leaving out much. Furthermore, I’m no professional historian, just a “popularizer” – which means I’m trying to be brief enough that people will actually read this! And obviously I’m writing from the Orthodox point of view. So, dear reader, if you think I’ve gone astray or forgotten something important, please add a comment at the bottom of this article.

Cardinal Humbert, the Papal emissary, placed this Papal bull * (greatly abbreviated here) on the altar of the great church Hagia Sophia in Constantinople on Saturday October 16, 1054, then walked out crying, “Let God be the judge!” The full text also mentioned that there was great good in the city, but it included a list of false accusations of heresy and misbehavior. Two of them, however, were accurate: 1) of using leavened Bread for the Eucharist (really?!) and 2) “of refusing to acknowedge the procession of the Son from the Father”. This was important – see below. The anathema applied directly to Michael Celularios, whom Humbert described as “falsely called Patriarch of Constantinople”, and his “followers”. The big issue here, of course, was whether the Orthodox Church would accept the Pope as having “the care of all the churches”. Patriarch Michael quickly returned the favor and excommunicated Cardinal Humbert and implicitly the Pope.

- In case you’ve wondered, a “bull” was a “bulla”, a leaden seal which authenticated its source. An anathema is a formal excommunication.

The year 1054 is usually given as the date of the Great Schism. Actually it wasn’t. For one thing, Cardinal Humbert did not excommunicate the other three Orthodox patriarchs, who were not under the jurisdiction of Constantinople. (I wonder if he realized that.) For another, when he laid the bull upon the altar at Constantinople, unknown to him the Pope had died, so technically the anathema didn’t count. The Great Schism was a process, not an event. There had already been the Photian Schism in the 9th century when Rome and Orthodoxy broke Communion for some time – this also over the issue of Papal supremacy and universal jurisdiction, after Pope Nicholas I attempted to depose Patriarch Photios of Constantinople. Orthodox consider Photios a brilliant scholar, a saint and defender of the Faith. Likewise for some time after 1054, many Orthodox and Roman Catholics did not break Communion – in parts of the Middle East and the Aegean islands, for example.

But back to the story.

What led up to the Great Schism.

Last week we looked at how cultural and historical differences caused Eastern and Western Christianity to diverge in “styles”, the West more legal and emphasizing external authority, the East less authoritarian, moving by consensus. These might have been held together in the Church for mutual benefit. So why did this lead to the Schism? Here is a very partial and cursory look at the reasons.

1 Lack of mutual understanding. For several centuries, few in the Latin West could any longer speak Greek, and hardly anybody in the Orthodox East cared to speak Latin. As you know, words do not translate easily from one language to another. Many nuances are missed. (Try to translate English into Korean, and vice versa. Surely they didn’t say that? Well, maybe they didn’t.) Also, travel on the Mediterranean had become very difficult because of invading Saracens and pirates. You know what happens when people don’t talk person to person. (I often wonder if impersonal e-mails and texts and Twitters are causing most of our contemporary problems.)

2 After the fall of Rome and the western part of the Empire to north European pagans (my ancestors!), how easy it was for Easterners to look down upon and ignore the West as barbarians. (Do we ever consider, for example, how Iranians with their 3000 years of civilization and imperial history must view us “upstart” Americans and our pretensions?) And when in the year 800 Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne, who could scarcely read a word, as emperor of a new competing western Roman empire… well, you can imagine.

3 The “Donation of Constantine”, a document fabricated in the 8th or 9th centuries, probably in France, which claimed that the Emperor Constantine had given the Pope of Rome authority over all Christians and even political power over the West. (They were never quite able to pull that one off!) This was little used in polemic before the Great Schism, but to the Papacy it justified their claims. Papal supremacy was news to the Orthodox East which had never known any such thing. Indeed when Rome first began to claim universal jurisdiction, the Orthodox didn’t take it seriously for a while.

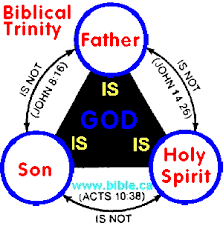

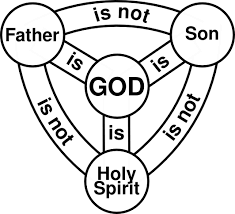

4 And then the “Filioque”, the phrase “and the Son” which the West added to the text of the Ecumenical Creed. This seems to have originated in the 6th century in Spain, apparently out of a desire to counter the Arian belief that Christ was not truly God. To make it crystal clear that God the Son was equal with God the Father, they added “We believe in the Holy Spirit who proceeds from the Father and the Son.” This was then strongly promoted by Charlemagne and the Franks (who were Christian by now) where Arianism was particularly strong. Rome resisted. To make the point, Pope Leo III had the original Creed without the Filioque carved on two silver (some say bronze) tablets and placed in the old Saint Peter’s Church in Rome. But in 1014, under political pressure, Rome gave in, and the Filioque became part of the Roman Catholic Creed, and has been ever since. Only forty years later Rome was chastising Orthodoxy for not using it!

In the Orthodox view, the Papacy is the big eccesiological problem. The Filioque is the big theological issue. We haven’t talked about it, so let’s stop and take a look.

The Filioque

Why so much fuss about three little words? I’m tempted to comment that the three little words “I love you” can make all the difference in the world!

Here are our issues with the Filioque:

1 It violates the canons of the Third Ecumenical Council of 431 which specifically forbade and anathematized any who make additions to the Ecumenical Creed. (Where have we heard that word “anathema” before?) The assumption behind this addition clearly was that Rome by herself has the authority to overrule the Church’s ecumenical Tradition and canons. If Rome does not have that authority… well, you figure it out for yourself.

2 It is contrary to the Scriptures. Christ is “the only begotten of the Father” John 1:14 “But when the Comforter comes, whom I shall send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth who proceeds from the Father…” John 15:26 Was it Saint John of Damascus who wrote that we have no idea what is meant by “begotten” and “proceeds”, but we hold to it because that’s what Scripture says! Nor, by the way, do we know precisely how Christ sends the Spirit. God only knows. My old Methodist seminary professor said that we do well not to inquire too much into the inner “family life” of God.

3 The Filioque throws the Holy Trinity out of balance.

In the Scriptures and therefore in the Orthodox understanding, the Father is the Source of all things – see Genesis 1. By “promoting” the Son, the Holy Spirit is effectively “demoted”. The following is my personal opinion: I think this explains why in the West, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, the Holy Spirit comes and goes, so to speak. There have been alternating periods of “Spiritual revival” followed by periods of “Spiritual dryness”. Scholasticism then mysticism, legalism then the Charismatic movement and so on. Presently it’s going dry again. Have you been to a typical American Mass lately? (I don’t want to offend Roman Catholic readers, but where has the sense of mystery and holiness gone?) Meanwhile Orthodoxy continues quietly, calmly, in unity led by the Spirit. Often this isn’t obvious from the outside. One needs to experience it from the inside. After I got accustomed to the Orthodox Liturgy, I discovered that it was the most Spirit-filled thing I had ever known. Some years ago we had a Pentecostal visitor at our Sunday Liturgy at Saint Nicholas. I wondered how he would react. Afterwards he said, “You’re more formal than us. But you’re doing exactly what we do: 2 hours of praising God in the Spirit.” I don’t mean to brag. This is not the result of our effort. Actually it’s our lack of effort. It comes, I think, simply because we have never “messed around” with the Creed. That is my opinion.

Results of the Great Schism in the East

The Schism between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism might have remained an issue mostly for bishops and theologians except for one thing: the Fourth Crusade and the sack of Constantinople. In 1204 Crusaders (who on previous quests had ravaged only the Middle East – Muslims, Christians and Jews alike) attacked Constantinople. Innocents were massacred, churches and homes pillaged and burnt, nuns raped, relics destroyed or stolen. (That’s why many Eastern relics are now in the West.) I cannot imagine that this was at the direction of Rome.  Nevertheless, the Latins took advantage of the situation. Baldwin I of Flanders was declared emperor of Constantinople. They set up a Latin hierarchy. After 57 years the Latins were driven out, but this so weakened the Roman (“Byzantine”) Empire in the east that it never recovered its strength.

Nevertheless, the Latins took advantage of the situation. Baldwin I of Flanders was declared emperor of Constantinople. They set up a Latin hierarchy. After 57 years the Latins were driven out, but this so weakened the Roman (“Byzantine”) Empire in the east that it never recovered its strength.

The Turks took advantage, and in 1453 “The City”, as it had long been called in both East and West, fell easily to them. The longest lasting and perhaps most influential Empire in history was gone. The Orthodox (Greeks especially) have never forgotten nor forgiven. This left among Orthodox people a permanent and popular hatred and distrust of Rome and the West which remains to this day. When I was in Greece in 1985 the speakers (well educated lay theologians) at the conference I attended made sure we Westerners understood: “Do you know what the Crusaders did to us?” Lost Byzantium. Centuries of Turkish oppression.

So in the end the Orthodox people rejected any who tried to make peace with Rome and the West. There were later attempts to reunite Roman Catholicism with Orthodoxy. (I phrase it that way because Orthodox believe that the Roman Catholics left us, in doctrine, in ecclesiology.) But by the 15th century the state of Orthodoxy was so weak that we went as beggars. Bishops appointed by the Patriarch and the Emperor went to a council in Florence seeking reunion, but actually it was because the Emperor wanted Western military help against the surrounding Turkish armies. The Orthodox bishops “sold out” – there’s no other way to put it – except for Mark of Ephesus who refused to sign. When they returned home  Mark became a popular hero, while the others were driven out of office. (I told you last week that all Orthodox are guardians of the Faith.) The popular saying was “Better the Turkish turban than the Papal tiara”. The Turks might give Orthodox a lot of trouble (as they did), but at least they wouldn’t try to destroy the Orthodox Faith. And that’s where things stood till modern times.

Mark became a popular hero, while the others were driven out of office. (I told you last week that all Orthodox are guardians of the Faith.) The popular saying was “Better the Turkish turban than the Papal tiara”. The Turks might give Orthodox a lot of trouble (as they did), but at least they wouldn’t try to destroy the Orthodox Faith. And that’s where things stood till modern times.

I warned you last week that it was going to take three articles to finish this. (Just wait till we come to the ten gazillion Protestant denominations!) Last week’s question was “Is the Pope Catholic?” The answer will lie in our different understandings of “Catholic”. Stay tuned.

Next Week: 1) Results of the Great Schism in the West: new doctrines and dogmas 2) What we still have in common 3) Movement toward unity 4) Hindrances to unity

Fr. Bill, Thank you so much for this series of essays. I was hoping to find clearer understanding of the differences between Orthodox and Roman Catholic. Now I hope to understand the different Orthodox churches that seem to come under different umbrellas – there’s Greek, Russian, Antiochian, Eastern. I am so confused. I can’t seem to figure out where I might want to go visit. I’m in Brooklyn NY

You’re welcome. If you’re confused now, wait till I try to describe Protestantism. Briefly, all Orthodox Churches believe exactly the same things. Likewise worship is almost identical, though with different national or regional music. Once you get accustomed to that a person feels at home anywhere. I walk into a church in Greece and almost immediately know where they are in the services. Antiochians and OCA (formerly Russian) are almost always in English. In other jurisdictions it varies. People are usually friendly, I think, but sometimes in churches with many new immigrants they’re hesitant. That’s about it.

You are pretty much right on your point about crusaders abuses, pillaging, killings, etc.. There’s no way we can justify that kind of behavior; but my point is, why is the tendency to blame all the Roman church believers regarding this ? Plus, some comments that I heard very often from some orthodox people regarding the relics that were stolen from the Eastern churches . They say they prefer that the Roman church keeps the relics; at least by now, because they say that the relics are more safe where they are, because unfortunately the political situation and the lack of proper respect for the Christian faith and because of those things the safe keeping of the relics can be guaranteed . Thanks

1) When I was in seminary in 1964, for some reason I unthinkingly made a light-hearted comment about Sherman marching through Georgia. My roommate, who was from Georgia, exploded at me as if I had marched through Georgia myself 100 years previously burning towns and cities, and he wouldn’t talk to me for a while. That’s why. 2) In many cases the lost treasures that survived were safer in the West. But why shouldn’t they now be returned? Saint Titus was first bishop for Crete, which has been free of the Turkish oppression for over a hundred years. Yet after many heartfelt requests, it took till 1965, I think, for the Roman Catholic Church to return his head (only!) to his homeland. They kept the rest of him.

Hi Fr. Bill. Very helpful blog. Was just trying to explain the Catholics & their filioque business to my daughter. This was the first site that helped!

Thank you! I think it’s pointless to dig any deeper into it. As we Orthodox say regarding anything we can’t figure out: “It’s a mystery!” It keeps out of a lot of trouble.