Daily (but it’s mostly nightly) Life on Mount Athos

Why was I so impressed by how beautiful things were at night? Because on Athos one spends a lot of the night awake. My most distressing memory is of the Finnish guestmaster knocking on my door every morning at 3 a.m. saying, “Pater, Pater, the services are beginning. Wake up.” Actually he was being kind. The services had begun at 2 a.m. Orthros (Matins) commences at 3, and typically goes on till 5 or so, except on Sundays and feasts when it’s about three hours long. (I mentioned to Father Barnabas and Father Alexis that our Metropolitan Philip had recently put out a directive that we should celebrate “complete” Sunday Matins, leaving a full hour for it. They just smiled.) And then each day they go on to celebrate the Divine Liturgy. I was allowed to say the Creed in English! Above is Simonopetra Monastery where I hope they have no sleepwalking monks.

For a holy day (The Nativity of the Theotokos, old calendar), we had a 9 1/2 hour All-Night Vigil service, beginning at 11 p.m., concluding at 8:30 the next morning. I told Father Barnabas I didn’t think this would “fly” back home. But what you all might go for is that at this long service, after the Entrance at Vespers (about 1 a.m.), a few monks remained in church to continue to service, while the rest went out to get a cup of coffee and a snack to keep them going till morning! The longest All-Night Vigil they have is 17 1/2 hours. But all this is done with old world Orthodox flexibility. Worshippers come and go as they need to. During the 9 1/2 hour service, Father Barnabas and I both went back to our cells to catch a couple hours’ sleep. The kitchen crew left early to prepare breakfast, a

All told, the ordinary non-festival non-Lenten worship day totals about eight hours: about six hours leading up to dawn, and then Vespers and Compline in the evening. In addition each monk has his own time set aside for prayer in his cell, as well as duties for the upkeep of the monastery – kitchen work, cleaning, maintenance, gardening, whatever. It’s a busy life. Sleep is from about 8 p.m. to 2 a.m., with a morning nap if there’s time.

My Reactions to the Holy Mountain

I found my time on Mount Athos: 1) Physically exhausting. When the wake-up knock on my door came at 3 a.m., that was 7 p.m. Milwaukee time. I had both jet lag and Athos lag! I slept only in fits and spurts the whole time I was there.

2) Spiritually exhilarating. Since I was a priest I was invited to be in front with the monks and to do all the standings and sittings and leanings and veneratings and bowings and prostratings with them. I think I managed not to embarrass either myself or the USA too badly. Orthodox worship is essentially the same wherever one goes, so even though I am not proficient in Greek I could figure out what was going on, with the help of an occasional whisper or nudge from Father Barnabas or Father Alexis. I saw everything up close: the impressive level of the prayer life, the meticulously-performed services, the intense enthusiastic chanting, the candles illuminating the faces of the ancient icons and the faces of the monks as they chanted in the darkness, and Christ the Pantocrator ruling over all from the dome, high above. The images keep coming back to me again and again.

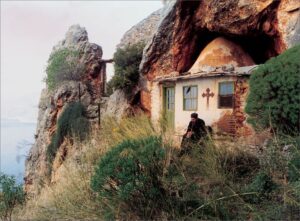

This gives something of the feel of it all.

3) Excessive, at least for me. I thought I liked long services. Little did I know. This was too much for me. I’m glad Mount Athos is there and prospering, setting high standards for Orthodox worship, preserving the Tradition entire, praying for us and the world. That is their work: prayer, worship, plumbing the spiritual depths. But I would never dream of trying to impose Athonite monastic worship on you or me in a parish church.

4) The whole time I was on the Holy Mountain I was immensely attracted to it all, and at the same time I wanted to get out of there as fast as I could. I had never experienced anything quite like this. My wife explained that it was the natural reaction to holiness. A century ago a Lutheran theologian Rudolf Otto wrote a book The Idea of the Holy, making the point that the numinous, that which is holy, both attracts and repels us sinners. Was that it?

One evening I had a conversation with a hermit. He lived alone in a cell up in the hills above Karakallou and came down for Sundays and feasts. What is your image of a hermit? This one was a chemical engineer with a special interest in medical ethics. He was Greek but had never taken the faith seriously until, while he was working in Montreal, living with a young woman, he read a theology book by Vladimir Lossky, and God touched him and then his girlfriend. He said they both repented and decided to become monastics. He lived at Karakallou for some years, then got the abbot’s blessing to become a hermit. He said his big problem was that he was spiritually lazy. His definition of “lazy” must have been different from mine. That evening after the 9 1/2 hour Vigil he asked me what I thought of the services, and I answered honestly (never lie to a hermit), “I think they are beautiful, but they are very long.” He looked at me as if he thought I had holes in my head. What is wrong with you, priest? Why would anyone not want to worship God for 9 1/2 hours straight?

said they both repented and decided to become monastics. He lived at Karakallou for some years, then got the abbot’s blessing to become a hermit. He said his big problem was that he was spiritually lazy. His definition of “lazy” must have been different from mine. That evening after the 9 1/2 hour Vigil he asked me what I thought of the services, and I answered honestly (never lie to a hermit), “I think they are beautiful, but they are very long.” He looked at me as if he thought I had holes in my head. What is wrong with you, priest? Why would anyone not want to worship God for 9 1/2 hours straight?

Now I’ll try to describe something indescribable. My last night at Karakallou I had a strange experience – caused by lack of sleep? divine intervention? both? I woke up and walked to the window. The moon and stars were bright, the noise of the waves gently touching the shore below, the lights of the island of Thassos far off across the sea. And (this is the indescribable part) somehow all things, the heavens, the earth, the sea, the monks on Athos, the people on Thassos, were moving in harmony, willingly, freely, solely out of love for God… and it was much more than that, but that’s as far as words will take me. I came out of it with a reverence for free will, for freedom, and an abhorrence of anything, anyone who tries to domineer over others, bully others, force others, control others, intimidate others, manipulate others. You can see I wouldn’t do well in modern politics! Don’t misunderstand. In society we need laws and enforcement to protect the poor and weak from the rich and powerful. But if it isn’t chosen freely, in the End what meaning does it have?

people on Thassos, were moving in harmony, willingly, freely, solely out of love for God… and it was much more than that, but that’s as far as words will take me. I came out of it with a reverence for free will, for freedom, and an abhorrence of anything, anyone who tries to domineer over others, bully others, force others, control others, intimidate others, manipulate others. You can see I wouldn’t do well in modern politics! Don’t misunderstand. In society we need laws and enforcement to protect the poor and weak from the rich and powerful. But if it isn’t chosen freely, in the End what meaning does it have?

Leaving the Holy Mountain

From the sublime to the ridiculous: On the way back I missed the bus in Ouranopolis and had an hour to kill, so I walked down to the seafront and sat on a bench in my priest’s outfit. Along came a German family (“Ach! picturesque Greek priest!”) who asked if they could take my picture. “Ne”(Greek for “yes”) I answered and tried to look as Greek as I could as they snapped away. Then I said, “Now I have something to tell you. I am not Greek. I am American, and my name is Olnhausen!” which is about as German as you can get. We all had a big laugh.

On the bus back to Thessaloniki, I found myself sitting there in my priest’s garb inadvertantly staring out the window at women – not salaciously, not at all – but I had missed women. I like women, and I love one woman in particular, and I definitely would not like to live in a permanently all-male world like Mount Athos. Not to mention a world without chocolate. The first thing I did when I got back to Thessaloniki was cut my hair and trim my beard, just to make the point that, as impressed as I was with the Holy Mountain, I am not a monastic. Thank God for Mount Athos. Thank God that I am a married American Orthodox parish priest.

And that is my report on Mount Athos.

Next time: My First Visit to Saint Nektarios, which I promise you is a good story.