Christ is risen!

I’m giving 4 Blog posts to Protestantism, since it is so extraordinarily complex – as you can see here, and this is only part of it.

.

What is Protestantism?

When Protestants ask “What do Orthodox believe?” there is an answer. All Orthodox believe the same things. When I was still Anglican, Father Thomas Hopko told me that “in the Orthodox Church there is complete theological unanimity”. I didn’t believe him. But it’s true.

But when Orthodox ask “What do Protestants believe?”, there are a thousand answers, ranging from almost Orthodox to almost Roman Catholic to almost disbelief. The best definition of “Protestant” I can come up with is this: “Protestants are members of any one of the many Western Christian groups which took on independent existence in the 1500s or later.”

If you Orthodox want to feel intimidated, consider: There are about 900 million Protestants in the world today, compared to about 250 million Eastern Orthodox. There are about 160 million Protestants in the United States, compared to about 2 million Eastern Orthodox on a good day. (We sometimes say 6 million Orthodox in the US, but I’d like to know where they all are.) On the other hand, as I said, we Orthodox are entirely united about the Faith, while Protestants go every which way. They are completely disunited, so it’s hard to see why they should be considered a single Christian group.

And if you want to feel much better: This, taken from an Ancient Faith  pamphlet, is the Orthodox view of things, with the Orthodox Church consistently united in the Apostolic Faith with no subtractions, no additions. (Enlarge it so you can see it. On a MacBook simultaneously push “Command” and the “Plus” sign on the upper right. If you’re not on Mac I have no words of advice.) I’m sorry the image is missing the first and last 3 centuries. Even without enlarging, you who are nearsighted can see that the Roman Catholics diverged from us halfway through Christian history, and the Protestants from the Roman Church 3/4 of the way. The Roman Catholic and Protestant lines should of course be much wider. Don’t mind that, you Orthodox. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “Which is more valuable, an elephant or a diamond?”

pamphlet, is the Orthodox view of things, with the Orthodox Church consistently united in the Apostolic Faith with no subtractions, no additions. (Enlarge it so you can see it. On a MacBook simultaneously push “Command” and the “Plus” sign on the upper right. If you’re not on Mac I have no words of advice.) I’m sorry the image is missing the first and last 3 centuries. Even without enlarging, you who are nearsighted can see that the Roman Catholics diverged from us halfway through Christian history, and the Protestants from the Roman Church 3/4 of the way. The Roman Catholic and Protestant lines should of course be much wider. Don’t mind that, you Orthodox. As C.S. Lewis wrote, “Which is more valuable, an elephant or a diamond?”

What Protestants Believe

Most Protestants adhere to Luther’s principle “Sola Scriptura”, Bible alone, but they have a multitude of different opinions about how to interpret the Scriptures. Others (many Anglicans, for example) believe that the Faith must also be grounded in Reason or Christian Tradition,  but then they disagree about exactly what that means. And in fact, all Protestants depend on more than the Scriptures, whether they admit it or not. For example, how often should they celebrate the Lord’s Supper? and using what forms? and where? The Bible doesn’t say, so Protestants either follow the Church’s Tradition to some extent or make up their own traditions.

but then they disagree about exactly what that means. And in fact, all Protestants depend on more than the Scriptures, whether they admit it or not. For example, how often should they celebrate the Lord’s Supper? and using what forms? and where? The Bible doesn’t say, so Protestants either follow the Church’s Tradition to some extent or make up their own traditions.

I think most Protestants (except for Anglicans and most Methodists) agree that any group of Christians has the right to form a new denominational structure or independent association and call that “church”. Because of this, one source now lists over 30,000 Protestant denominations in the world. That must include every little group in a store front. I can’t imagine how they tracked them all down. A few years ago our Milwaukee Yellow Pages listed 96 Protestant denominations including Churches of God; Churches of God, Anderson Indiana; Churches of God, Cleveland Tennessee; Churches of God in Christ; 12 kinds of Baptists, many independent groups – and of course the usual classical Protestant denominations which we’ll consider next week. All of them teach different things to a greater or lesser degree. Each of them believes that they have the true interpretation of the Scriptures or the authentic way of approaching the faith – obviously so, else they wouldn’t be teaching what they do. Even if they don’t acknowledge it, the “open-minded” liberal denominations also believe very firmly that being open-minded is the only way to go.

Are you hanging in so far? It’s going to get much more confusing as we go along. For example:

1 While Orthodoxy changes little through the centuries and Roman Catholics only in an ordered way, Protestant denominations may quickly change radically and with little control system. The Presbyterian Church, for example, was founded on John Calvin’s dreadful doctrine of Predestination, that God predestines each of us to heaven or hell without reference to our actions. Today few Presbyterians believe that. (And I say “Thank God”.)

2 Within most Protestant groups, individuals or parishes may disagree with denominational teachings. For years there were Anglo-Catholics within the “Protestant Episcopal Church” in America who vehemently denied that they were Protestants. Episcopalians eventually removed “Protestant” from their official title.

3 What Protestants say is not always what they believe. There have been Anglican bishops, for example, who publicly deny the divinity of Christ, the Resurrection, and the Holy Trinity, but then go to church and say the Creed. No problem. (I don’t mean to pick on Anglicans in particular, but that’s where I came from, and that’s what I know.)

4 Protestant social and moral teachings range from very conservative to very liberal, and these also may change, sometimes quickly.

How to get a handle on all this without getting a nervous breakdown?

My plan is to approach the subject historically. This week how Protestantism came to be. Next week the major denominations of the early Protestant movement – Lutherans, Calvinists, Anglicans, Baptists, Methodists – and we’ll see why Protestants became divided even in the first generation. Then we’ll catch a breath for a few weeks, and in the next and final segments we’ll consider 19th and 20th century developments, which led to the complete fragmentation of Protestantism.

I’ll try to be fair and balanced, but this is complicated. I’ll have to oversimplify and omit many, many things. If any of you readers are or have been Protestants, please forgive me, and correct me if I say anything inaccurate.

Martin Luther and the Origins of Protestantism

I wrote about Martin Luther in more detail back in Blog posts 35 and 36 but will repeat some of it here for the sake of those who haven’t read it.

There had been rumblings earlier, but the Protestant Reformation officially began on October 31, 1517, which today is celebrated by Lutherans and some other Protestants as Reformation Day. On that day a Roman Catholic monk Martin Luther nailed “95 Theses” to the door of a church (the community bulletin board) in Wittenberg,  Germany: 95 ways in which he said the late medieval Roman Catholic Church needed to be reformed. Europe was still recovering from plagues which had decimated communities, schools, monasteries and churches – and they had understandably been left with little teaching, much superstition. Popular religion consisted mostly of following rules. The papacy was often corrupt: Pope Alexander IV had named one of his sons Archbishop of Valencia!

Germany: 95 ways in which he said the late medieval Roman Catholic Church needed to be reformed. Europe was still recovering from plagues which had decimated communities, schools, monasteries and churches – and they had understandably been left with little teaching, much superstition. Popular religion consisted mostly of following rules. The papacy was often corrupt: Pope Alexander IV had named one of his sons Archbishop of Valencia!

The printing press had now been invented, and books were becoming available. Luther read the Bible, and in Romans he rediscovered the need for personal faith, trust in God, and his own faith came alive. There was at that time a campaign to raise funds to build the present Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Now, the Roman Church did not officially teach that money could buy souls out of purgatory; nevertheless a fundraising group came to Wittenberg singing a song “When a coin in the coffer rings, a soul out of purgatory springs.” Luther blew his stack, with good reason. Something had to be done.

So his 95 Theses were not only posted but printed and distributed, and since Rome was already unpopular north of the Alps, he gained much support. Luther did not intend to start a  new church. He wanted to reform the Roman Catholic Church, to protest (Latin: “testify for”), to witness for the Faith within the Church. However, Rome was not interested in reform. Their response was “Recant”. Luther refused. He said “Here I stand. I can do no other”. So the Pope excommunicated him and his followers, and Martin Luther very unwillingly wound up starting the Lutheran Church. Thus was established the principle that groups of Christians can gather on their own without higher authority and establish “churches”.

new church. He wanted to reform the Roman Catholic Church, to protest (Latin: “testify for”), to witness for the Faith within the Church. However, Rome was not interested in reform. Their response was “Recant”. Luther refused. He said “Here I stand. I can do no other”. So the Pope excommunicated him and his followers, and Martin Luther very unwillingly wound up starting the Lutheran Church. Thus was established the principle that groups of Christians can gather on their own without higher authority and establish “churches”.

The “Protestant Reformation”. You can see the turn Luther’s movement took: The word “protest” came to mean to “oppose” something. And the “Reformation” is now celebrated as the time not when the Church was reformed, but when a new ecclesiastical structure was created. Many Protestants for centuries defined themselves in opposition to Rome: We don’t pray for the dead or make the sign of the cross or whatever because “Catholics do that”. And they felt free to keep establishing new denominations.

Luther’s Teachings

Let’s dwell on Luther for a bit, because he set the fundamental principles for Protestantism. Luther was brilliant. Almost alone he formed the common German language. He was a strong charismatic leader: Lutheranism was shaped by him, obviously was named after him. Like most early Protestants he was orthodox in most ways: He believed in the Trinity, the Incarnation, the Creed. He honored the Virgin Mary and believed in private Confession. He restored good things: worship in popular language, receiving Holy Communion every Sunday, devotion to the Holy Scriptures, personal faith. And considering the state of the late medieval episcopacy, it’s not surprising that Luther saw little point to retaining the apostolic ministry.

But no one man can keep all things in balance, and Luther overreacted, as we all tend to do when pressed. He had rediscovered the Bible and so began to teach “Sola Scriptura” (Bible alone), no Church Tradition. He had rediscovered faith and began to teach that salvation comes by “faith alone”, that good works, how we act has nothing to do with it. These became the guiding principles of early Protestantism.

There were some problems here:

1 Salvation by faith alone is not Biblical teaching. It’s a misreading of a verse from Romans, which we can still hear today from many evangelical Protestants: “Christ died for our sins, and all we have to do is accept that on faith and we can go to heaven.” That’s a long way from Orthodox teaching that salvation is a slow process of making us over into the likeness of Christ. The New Testament is clear that good works are necessary. For example, read Matthew 25:31-46. James, the Lord’s brother, in his Epistle went out of his way to correct such a misunderstanding: “Faith without works is dead”. Luther called it an epistle of straw and wished he could throw it out of the Bible.

2 “Bible alone” is not Biblical! Where is that in the Bible? The Bible has never stood alone but rather within the Church. The Church was not built on the Bible; the New Testament was written from within the Church. But the even bigger problem was how to interpret the Bible. It’s not obvious as Luther thought. Soon came John Calvin who read the Bible very differently from Luther, and Anabaptists who said all may interpret the Bible as they wish (“each man his own pope”) which Luther opposed violently. (Literally he supported their massacre.)

who said all may interpret the Bible as they wish (“each man his own pope”) which Luther opposed violently. (Literally he supported their massacre.)

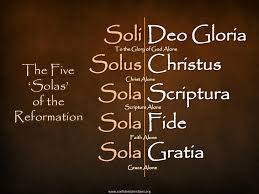

As time went on Luther’s followers, following his pattern,  have tended to isolate elements of the Faith, as you can see to the right, rather than integrating them as the Fathers did, as we Orthodox do. There is a “Christ Alone” movement in the Wisconsin Lutheran Synod today. Every time I drive past one of their signs, I want to stop and ask, “But, but… what about the Father and the Holy Spirit?”

have tended to isolate elements of the Faith, as you can see to the right, rather than integrating them as the Fathers did, as we Orthodox do. There is a “Christ Alone” movement in the Wisconsin Lutheran Synod today. Every time I drive past one of their signs, I want to stop and ask, “But, but… what about the Father and the Holy Spirit?”

Late in life Luther sometimes wondered if he had done the wrong thing.

Next Week: the Classical Protestant Denominations

Good evening! When you say the Orthodox have complete theological unanimity, are you saying there are absolutely no divisions of Liturgical Worship and teachings & beliefs of the faith?

Thankyou & God bless!

Yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying. Almost. Regarding “teaching and beliefs”, I was amazed when I first became Orthodox to find that when clergy got together we all agreed about the faith. Of course different people will emphasize different aspects of it, but there is no argument whatsoever about what “it” is. Regarding worship, there are very minor differences in the texts between Byzantines (Greeks/Antiochians) and Orthodox who come from farther north. There are differences in musical styles and language from one culture to another. Also in various churches people may participate more or less and receive Holy Communion more or less frequently. I’m speaking here of us “Eastern Orthodox” Christians. “Oriental Orthodox” (Armenians, Egyptians, some Syrians) have somewhat different worship forms and theology.

Thankyou for your response; I can see that there is little if any differences – just as you said emphasis on various aspects and that would be right according to one’s specific area of interest – ex: scripture, music, sacraments – tks again! God bless…..

What about the Russian Church that is not in communion with most of the Orthodox churches. What about Luther’s last words “we are beggars”? What about the martyrs of the reformation? In the Orthodox and Catholic churches nobody knew what’s going on during liturgy because it was held in greek, latin or slavic? Who brought the Bible to the people? Who made them understand God’s words? There were so many martyrs during the first centuries of the reformation…They diec for their faith.

Thanks for your comment. Wow – that Post was a long time ago, so I went back to read it to see if I still agree with myself, and to find out what your questions refer to. I’ll try to answer them briefly one by one:

1) All Orthodox agree entirely about the Faith, but we’ve always had difficulties with “structural” unity. The present disunity is over politics. I don’t pretend to know who’s right, but I think we should withdraw from Communion only if there is disagreement about the Faith. I think the present disunity is embarrassing, to put it mildly.

2) I think in the Post I said many good things about Luther – that he brought the Bible to the German people. and that the break with the RC Church was not his fault. I said only that his understanaing of things was limited, as with everybody’s including mine, so you are right to challenge me. I wish more people would!

3) Latin, Greek and Slavonic were originally the languages of the people. It is a failing of both the Orthodox and RC churches that we did not keep up with the change in popular language. The reason was that during times of persecution or instability, people tend to cling to things as they were. Not to justify this, but in all these cases the Faith is taught not only through language but through icons, music, etc., and it hasn’t changed – except in the RC Church in recent years, especially after they went into the popular language! Meanwhile, as I wrote, Protestants, despite being in the language of the people, now have a multitude of different understandings of the faith. Orthodoxy has been slowest to adapt, for the same reasons. However, things are changing, many Orthodox churches are moving into the language of the people. Many people have come to our Saint Nicholas, Cedarburg and have been excited to hear the Liturgy and Scriptures in terms they understand. And as we go “popular”, there has been no change in our Faith.

4) God bless any who are martyred for what they believe it. And a curse on those who kill them.

Thank you for writing and asking.

Father bill