Forgive me again. This week I’m a day late. *

- Personal note: I’m ok, Carlos.

As I said last week, I’m writing here about something I don’t know much about. A man pretending to understand women? Nonsense. (I hope that wasn’t a sexist comment…)

Therefore in these two Posts we’re trying to learn directly from the source: last week from some female friends of mine and also another one very close to me, and then we looked at Saint Olga, whose feast day was July 11. This week it’s Macrina the Younger whom we celebrate on July 19 and her grandmother Macrina the Elder, who is honored on May 30, also on January 14. And I have realized that we should add the younger Saint Macrina’s mother Saint Emelia.

Because my time for original writing is very limited again this week, I’m going to borrow a lot from the website of my Antiochian Archdiocese.

Saint Macrina the Elder

“St. Macrina was the mother of St. Basil the Elder, and the grandmother of St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Peter of Sebaste, and St. Macrina the Younger.

“St. Macrina lived in Neocaesarea [now Niksar in central Turkey] during the persecution of Christians under Galerius in the late third and early fourth centuries. In her childhood, she became acquainted with St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, the first bishop of Neocaesarea, who was responsible for converting the entire Christian population of that city to Christianity.

“During the persecution of Christians under Emperor Diocletian, Macrina fled with her husband to the forest near their home. They endured many hardships, but patiently waited and prayed for the persecutions to end. They survived on vegetables and wild game for over seven years. When they were free to return, they discovered that their belongings and property had been taken from them.

“She raised her grandchildren in the Christian faith, and St. Basil was one of her favorites. As an adult, he praised her for all the good she had done to him and thanked her for teaching him to love Christ.

“Saint Macrina survived her husband and died around 340.”

From the Antiochian Archdiocese, by permission of www.abbamoses.com and www.orthodoxwiki.org and www.abbamoses.com

The only words I want to add come directly from her grandsons:

“Some time ago, there had been a celebrated Macrina in our family, our father’s mother. At the time of the persecutions she had suffered bravely for her confessions of faith in Christ, and it was in honor of her that the child was given this name by her parents.” Gregory of Nyssa: “Life of Macrina the Elder”.

“What clearer evidence can there be of my faith, than that I was brought up by my grandmother, a blessed woman, who came from you. I mean the celebrated Macrina who taught me the words of the blessed Gregory, which, as far as memory had preserved down to her day, she cherished herself, while she fashioned and formed me, while yet a child, upon the doctrines of piety.”

“The teaching about God which I had received as a boy from my blessed mother and my grandmother Macrina, I have ever held with increased conviction. On my coming to ripe years of reason I did not shift my opinions from one to another, but carried out the principles delivered to me by my parents. Just as the seed when it grows if first tiny and then gets bigger but always preserves its identity, not changed in kind though gradually perfected in growth, so I reckon the same doctrine to have grown in my case through gradually advancing stages. What I hold now has not replaced what I held at the beginning.” Saint Basil the Great: “Letter 204 to the Church in Neocaesarea”

It’s interesting that we hear very little of her husband, not even his name, so far as I know.

Saint Macrina the Younger and her mother Emilia

This also is from my Antiochian Archdiocese, with permission of the OCA.

“St. Macrina was the sister of the holy hierarchs Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa, and was born in Cappadocia in the early fourth century. Her mother, Emilia, saw an angel in a dream and named her unborn child, Thekla, in honor of the holy Protomartyr Thekla. Another daughter was named Macrina, in honor of a grandmother, who suffered during the persecutions under Emperor Maximian Galerius.

“Besides Macrina, there were nine other children. St. Emilia became responsible for the upbringing and education of her elder daughter. She taught her reading and writing from the Scriptural books and Psalms of David, selecting examples from the sacred books which spoke of a pious and God-pleasing life. St. Emilia taught her daughter to pray and to attend church services. Macrina was also taught how to run a household and learned various handicrafts. She was never left idle and did not participate in childish games or amusements.

When Macrina was a teenager, her parents betrothed her to a pious young man, but the bridegroom soon died. Many young men wished to marry her, but Macrina refused them all, having chosen the life of a virgin and not wanting to be unfaithful to the memory of her dead fiancée. Macrina continued to live in the home of her parents, assisting the servants with household tasks, as well as helping with the upbringing of her younger brothers and sisters. After the death of her father, she became the chief support for the family.

“After her other siblings grew up and left home, Macrina convinced her mother to settle in a women’s monastery. Several of the servants followed their example. Having taken monastic vows, they lived together as one family – they prayed together, worked together, and possessed everything in common.

“After the death of her mother, St. Macrina guided the sisters of the monastery. She enjoyed the deep respect of all who knew her. Strictness towards herself and temperance in everything were characteristic of the saint all her life. She slept on boards and had no possessions.

“She was also granted the gift of wonderworking. There was an instance (told by the sisters of the monastery to St. Gregory of Nyssa after the death of St. Macrina) when she healed a girl of an eye-affliction. Through her prayers, there was no shortage of wheat at her monastery in times of famine.

“St. Macrina died in 380, after a final prayer of thanks to the Lord for having received His blessings over all the course of her life. She was buried in the same grave with her parents.”

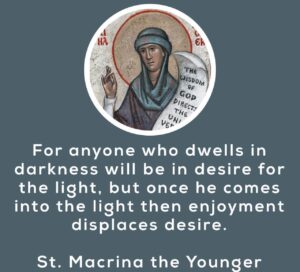

About Saint Macrina the Younger, let me add only this long but very moving passage about her death. This was what drew me to her years ago. It’s taken from The Life of Saint Macrina written by her brother Saint Gregory of Nyssa. After the death of his friend and brother Saint Basil, he went into a period of deep mourning – it sounds like “situational depression”. Then for consolation he went to visit his sister Macrina for the first time in some years, only to find her on her deathbed.

“Most of the day had now passed, and the sun was declining towards the West. Her eagerness did not diminish, but as she approached her end, as if she discerned the beauty of the Bridegroom more clearly, she hastened towards the Beloved with the greater eagerness. Such thoughts as these did she utter, no longer to us who were present, but to Him in person on Whom she gazed fixedly. Her couch had been turned towards the East; and, ceasing to converse with us, she spoke henceforward to God in prayer, making supplication with her hands and whispering with a low voice, so that we could just hear what was said. Such was the prayer; we need not doubt that it reached God and that she, too, was hearing His voice:

“’You, O Lord, have freed us from the fear of death. You have made the end of this life the beginning to us of true life. You for a season rest our bodies in sleep and awake them again at the last trump. You give our earth, which You have fashioned with Your hands, to the earth to keep in safety. One day You will take again what You have given, transfiguring with immortality and grace our mortal and unsightly remains. You have saved us from the curse and from sin, having become both for our sakes. You have broken the heads of the dragon who had seized us with his jaws, in the yawning gulf of disobedience. You have shown us the way of resurrection, having broken the gates of .hell, and brought to nought him who had the power of death—-the devil. You have given a sign to those who fear  You in the symbol of the Holy Cross, to destroy the adversary and save our life. O God eternal, to Whom I have been attached from my mother’s womb, Whom my soul has loved with all its strength, to Whom I have dedicated both my flesh and my soul from my youth up until now—- give me an angel of light to conduct me to the place of refreshment, where is the water of rest, in the bosom of the holy Fathers. You who broke the flaming sword and restored to Paradise the man who was crucified with You and implored Your mercies, remember me, too, in Your kingdom; because I, too, was crucified with You, having nailed my flesh to the cross for fear of You, and of Your judgments have I been afraid. Let not the terrible chasm separate me from Your elect. Nor let the Slanderer stand against me in the way; nor let my sin be found before Your eyes, if in anything I have sinned in word or deed or thought, led astray by the weakness of our nature. O You Who have power on earth to forgive sins, forgive me, that I may be refreshed and may be found before You when I put off my body, without defilement on my soul. But may my soul be received into Your hands spotless and undefiled, as an offering before You.’

You in the symbol of the Holy Cross, to destroy the adversary and save our life. O God eternal, to Whom I have been attached from my mother’s womb, Whom my soul has loved with all its strength, to Whom I have dedicated both my flesh and my soul from my youth up until now—- give me an angel of light to conduct me to the place of refreshment, where is the water of rest, in the bosom of the holy Fathers. You who broke the flaming sword and restored to Paradise the man who was crucified with You and implored Your mercies, remember me, too, in Your kingdom; because I, too, was crucified with You, having nailed my flesh to the cross for fear of You, and of Your judgments have I been afraid. Let not the terrible chasm separate me from Your elect. Nor let the Slanderer stand against me in the way; nor let my sin be found before Your eyes, if in anything I have sinned in word or deed or thought, led astray by the weakness of our nature. O You Who have power on earth to forgive sins, forgive me, that I may be refreshed and may be found before You when I put off my body, without defilement on my soul. But may my soul be received into Your hands spotless and undefiled, as an offering before You.’

“As she said these words she sealed her eyes and mouth and heart with the cross. And gradually her tongue dried up with the fever, she could articulate her words no longer, and her voice died away, and only by the trembling of her lips and the motion of her hands did we recognise that she was praying.

“Meanwhile evening had come and a lamp was brought in. All at once she opened the orb of her eyes and looked towards the light, clearly wanting to repeat the thanksgiving sung at the Lighting of the Lamps. But her voice failed and she fulfilled her intention in the heart and by moving her hands, while her lips stirred in sympathy with her inward desire. But when she had finished the thanksgiving, and her hand brought to her face to make the Sign had signified the end of the prayer, she drew a great deep breath and closed her life and her prayer together.”

After her death, the wailing of her sister monastics was so loud that Gregory had to shout so they could hear him.

___________________________________

Here were three women whose roles were quite different, except that they all clearly were the spiritual leaders of their family. None of the three had a public role, such as did Saint Olga last week, but they nevertheless had a profound effect on the world, which endures to this day – else I wouldn’t be writing a column about them, would I?

The roles of these four women

Saint Olga, whom we looked at last week, lived a public life. She had power and wealth, which she increasingly used for good, and to bring her people to Orthodox Christianity. However, as you’ll remember, she did not live to see the fruits of her labor, not even with her son.

Today’s three saints lived private lives, devoted to their families.

Macrina the Elder with her husband led their family into the wilderness, giving up wealth, living in utter simplicity. She lived to see her family become devout Christians, though she couldn’t have imagined the effect her grandchildren would have on the world.

Emilia, though having regained wealth, then gave it up for the simplest of monastic living. By the time she died, her son Basil was a bishop.

Macrina who also abandoned her wealth, and was the one to whom her brothers turned for advice and consolation.

With these three Cappadocian women, what comes through above all is the love, warmth, affection, respect their families had for them, and as a result for each other, They loved their children/grandchildren and worked to shape them in the Faith. And, unless there are things we don’t know, they were the dominant spiritual influences in their families.

There are a multitude of other saintly women we could consider, but I think these four well illustrate some of their varying roles. I think that’s all I have to say about that. We have just been looking at them and trying to learn from them.

Women in the Orthodox Church today

Does our contemporary situation require some additional possibilities? After all, in the past decades women have taken an increasingly public role all over the world, excepting a few arch-conservative Muslim countries. We see many women now in politics, the media, academia, law, medicine to a degree not imaginable even when I was a boy. It appears to me that society has gained much from this, now that we no longer waste all that feminine talent. I believe we men are learning much and gaining insights from the feminine viewpoint.

Today Orthodox women continue to teach children in our parishes and do what they’ve always done. We all know the Church couldn’t function without them. (Remember last week’s comment: “Why would we want that [to be priests]? We already run the Church!”) Women serve now without controversy on Parish Councils and in all sorts of advisory and “pastoral” ways.

I note that today there are more women in our Orthodox seminaries – which only a few years ago was strictly male turf. Since the sacramental priesthood and the episcopate are clearly going to remain exclusively male. * I trust these talented women are teaching or taking on “pastoral” ministries in schools or larger parishes. However the great majority of Orthodox parishes are not large enough to afford to pay more a priest, so only rarely do we see women taking a public role.

- I agree with this, though again I can’t exactly define why. Nor can anyone else. There are a number of arguments now floating around to explain it, but we can’t quote the Fathers on this because it wasn’t an issue then, and Orthodoxy tends not to define matters till they are challenged – and even then it takes a while.

Should the Order of Deaconesses be revived? There certainly is precedent for that in the Scriptures and the early Church. I read (though I haven’t seen it documented) that Saint Nektarios of Aegina ordained a Deaconess of two. Anciently Deaconesses apparently ministered only to women. The modern world being what it is, could that be altered? Say, could a Deaconess give the homily? We might learn some things. (We know women can be very effective teachers.) In light of the effect our three Cappadocian women had on their families, could a woman have the same effect within a “parish family”?

I’m just speculating.

So, if you had to put it all together, how would you answer these two questions:

1 Speaking in generalities, how would you describe the traditional role of women in the Orthodox Church?

2 What should be the role of women in the Orthodox Church today?

I’m waiting for your comments – below.

_________________________________

In researching this paper, I discovered that Saint Macrina the Younger is venerated by Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Anglicans and… I came across what I thought was the most readable account of her life and wondered who wrote it. At the end I found out: Jonathon Arnold, a Methodist pastor. See: https://holyjoys.org/macrina-younger/

Next Week: A bunch of things I’ve been saving up

Week after next: I haven’t the faintest.