Why, you may ask, am I giving two Posts in an  Orthodox Blog to an Anglican and his writings?

Orthodox Blog to an Anglican and his writings?

It’s because I’ve been waiting over four years for an excuse to do this! and this is the excuse:

During Pascha and Ascension season, we’ve been looking at Heaven, where Christ went “to prepare a Place” for us – what our Lord Jesus taught, Saint John in The Revelation, last week Saint Ephraim of Syria’s Hymns on Paradise. C.S. Lewis also wrote about Heaven, and did so in a Scriptural Patristic way. In fact, I’d be willing to bet that he took some of his imagery from Hymns on Paradise.

First let’s look at CSL himself, the best-selling and most influential Christian author of the Twentieth Century.

Then, this week and next, we’ll look at two of his writings about Heaven.

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis made me Orthodox. His’ ideal was “mere Christianity” – the mainstream of what Christians have believed and practiced through the centuries. I finally concluded that “mere Christianity” today is Holy Orthodoxy – and it always was. Lewis is still having that effect. A young Evangelical man emailed me just this week that the sort of thing C.S. Lewis wrote “has led me to Orthodoxy”.

I don’t think Lewis didn’t meant to do this. He was Church of England. In the mid Twentieth Century when he wrote, a case could still be made that Anglicanism was “mere Christianity”. Archbishop of Canterbury Geoffrey Fisher wrote “We have no doctrine of our own. We only possess the Catholic doctrine of the Catholic Church enshrined in the Catholic Creeds, and these creeds we hold without addition or diminution. We stand firm on that rock”. (How accurate that was is another question, of course.) At the time, Orthodoxy in Britain was still nearly inaccessible – tiny and almost entirely Greek or Slavonic.

With all that has happened in the past sixty years, would Lewis still be Anglican today? That’s one of those unanswerable “what if…?” questions.

I’ve long thought C.S. Lewis was as orthodox as one can be without being Orthodox. I’m not alone in that opinion: I’m told Father Thomas Hopko from Saint Vladimir’s Seminary used to refer to him as “Our Holy Father C.S. Lewis”!

And on a trip to Greece, late in his life, CSL discovered that he loved Orthodox Liturgy, and he was deeply impressed by the spirituality of Orthodox priests. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote an article: “C.S. Lewis: an Anonymous Orthodox?” which I can’t locate, but you can read about it at: https://orthodoxwiki.org/C._S._Lewis

Lately, after having been Orthodox for over thirty years, I’ve gone back to Lewis’ writings to see if I’ve changed my opinion of him. I now have a couple of quibbles here and there. For example, in Mere Christianity he spends too much time trying to justify the unjustifiable Western approach to justification. But that’s about it. If you don’t mind my saying so, I think Lewis was steadier and more balanced in the Faith of the Church than some Orthodox writers I could mention, but won’t.

Lewis was grounded in the Scriptures and the Fathers, though he didn’t quote them very often. He must have known the Fathers well: where else could his Patristic Christianity have come from? In both cases he seems to have integrated them into his thinking, and then he taught the historic Faith.

I think Lewis did more than anyone else to defend and further traditional Christianity in this increasingly secular age here in the West. This was not only because of what he wrote but also because of how he wrote: He presented the Faith  in a wonderfully down-to-earth, accessible, easily readable, imaginative, “popular”, sometimes even humorous way. If you’ve followed this Blog regularly, you know how often I quote him.

in a wonderfully down-to-earth, accessible, easily readable, imaginative, “popular”, sometimes even humorous way. If you’ve followed this Blog regularly, you know how often I quote him.

I decided long ago that if people can’t explain it simply, that means they don’t really understand what they’re talking about. * Lewis understood the Faith. Over the years I’ve tried to pattern my writing and preaching style after him. If, on occasion, you find what I say hard to follow, that means I don’t know what I’m talking about.

- There is, of course, a place for “technical” theological literature, too.

Every day I pray for the soul of “Jack”, as he liked to be called. (He hated “Clive Staples”.)

I can’t resist some side notes about him before we proceed:

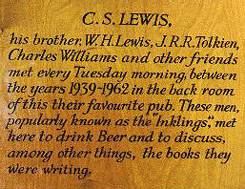

1 Did you know that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, were good friends. They met regularly with others at a pub in Oxford – The Eagle and the Child, which they nicknamed “The Bird and the Baby” – to smoke (sorry) and drink beer and discuss their ideas. When we visited Oxford, Khouria Dianna and I had a beer there in his memory.

A plaque in the pub.

2 C.S. Lewis attended the Holy Eucharist and received Holy Communion weekly at his parish church, went to Confession regularly and believed, as we shall see, in an essentially “Orthodox” form of Purgatory – though we wouldn’t use that word. I wonder how many of his numerous Evangelical followers take note of this.

3 Hardly anybody seems to pay attention to CSL’s social views, so let’s spend some time on this:

Lewis despised politics and most politicians. He thought the real solutions lay elsewhere. In The Silver Chair, a book from The Chronicles of Narnia series, Aslan the Great Lion (the Christ figure) arrives and drives out an incompetent school teacher who was nasty to children. He adds that first the “authorities” found her other work, “And when they found she wasn’t much good even at that, they got her into Parliament where she lived happily ever after”!

However… Lewis corresponded regularly with an enormous number of people, both adults and children. One of these was an American woman who had a life-threatening illness and was terrified because she hadn’t money to pay for medical treatment. He wrote: “What you have gone through begins to reconcile me to our Welfare State of which I have said so many hard things. “National Health Service” with free treatments has its drawbacks––one being that Doctors are incessantly pestered by people who have nothing wrong with them. But it is better than leaving people to sink or swim on their own resources.” Letters to an American Lady, 1950

This is part of what he wrote in Mere Christianity:

“… the New Testament, without going into details, gives us a pretty clear hint of what a fully Christian society would be like. Perhaps it gives us more than we can take.

“It tells us that there are to be no passengers or parasites: if man does not work, he ought not to eat. Every one is to work with his own hands, and what is more, every one’s work is to produce something good: there will be no manufacture of silly luxuries and then of sillier advertisements to persuade us  to buy them… To that extent a Christian society would be what we now call Leftist. On the other hand, it is always insisting on obedience—obedience (and outward marks of respect) from all of us to properly appointed magistrates, from children to parents, and (I am afraid this is going to be very unpopular) from wives to husbands. * Thirdly, it is to be a cheerful society: full of singing and rejoicing, and regarding worry or anxiety as wrong. Courtesy is one of the Christian virtues…

to buy them… To that extent a Christian society would be what we now call Leftist. On the other hand, it is always insisting on obedience—obedience (and outward marks of respect) from all of us to properly appointed magistrates, from children to parents, and (I am afraid this is going to be very unpopular) from wives to husbands. * Thirdly, it is to be a cheerful society: full of singing and rejoicing, and regarding worry or anxiety as wrong. Courtesy is one of the Christian virtues…

- Note: He wasn’t yet married when he wrote this!

“If there were such a society in existence and you or I visited it, I think we should come away with a curious impression. We should feel that its economic life was very socialistic and, in that sense, ‘advanced’, but that its family life and its code of manners were rather old fashioned—perhaps even ceremonious and aristocratic. Each of us would like some bits of it, but I am afraid very few of us would like the whole thing. … That is why we do not get much further: and that is why people who are fighting for quite opposite things can both say they are fighting for Christianity.”

“Now another point. There is one bit of advice given to us by the ancient heathen Greeks, and by the Jews in the Old Testament, and by the great Christian teachers of the Middle Ages, which the modern economic system has completely disobeyed. All these people told us not to lend money at interest: and lending money at interest—what we call investment—is the basis of our whole system”

I’ve been wanting to talk about that for a long time, and now I’ve got it out of my system. I trust all that stimulated your brain. I feel a future Post or three coming on.

Now to today’s subject. There’ll be few images, for most of what Lewis describes is not imagable.

The Great Divorce

This is not about marriage problems!

The Great Divorce refers to the divide between Heaven and hell – the choice which each of us must make before The End – and the various reasons people have for now rejecting Heaven and Joy. The real point of the book is that if we don’t want Heaven in this life, why should we think we’ll want it after we die? The characters and conversation in the book are very mid-Twentieth Century British. Work your way through that, and maybe you’ll see some people you know. Perhaps you’ll even see yourself. If you haven’t read The Great Divorce, read it!

However, here we’ll look only at how Lewis pictured Heaven.

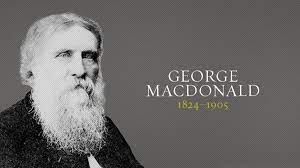

Dante had Virgil to guide him through purgatory and hell, and Beatrice to guide him into Heaven. Just so, Lewis has a guide: George MacDonald, an obscure 19th century Scottish author, whose writings I found to be peculiar, at best, but he had been important in waking Lewis’ imagination to Greater Things.

Dante had Virgil to guide him through purgatory and hell, and Beatrice to guide him into Heaven. Just so, Lewis has a guide: George MacDonald, an obscure 19th century Scottish author, whose writings I found to be peculiar, at best, but he had been important in waking Lewis’ imagination to Greater Things.

Lewis makes it clear that The Great Divorce is fiction. Near the end, his guide warns “See ye make it very plain. Give no poor fool the pretext to think ye are claiming knowledge of what no mortal knows.”

The Outskirts of Heaven

In what follows, words in italics are my own commentary.

In his fictional dream, Lewis discovers that after death people find themselves in a drab, dreary, grey town. From there they may take a bus trip (!) to the outskirts of Heaven – and Lewis imagines himself going along.

The bus arrives:

“The light and coolness that drenched me were like those of summer morning, early morning a minute of two before the sunrise… I had the sense of being in a larger space, perhaps even a larger sort of space, than I had ever known before: as if the sky were further off and the extent of the green plain wider than they could be on this little ball of earth. I had got ‘out’ in some sense which made the Solar Shystem itself seem an indoor affair. It gave me a feeling of freedom, but also of exposure, possibly of danger, which continued to accompany me through all that followed.” Chapter 3

What startled him most was this:

“In the light [people] were transparent… smudgy and imperfectly opaque… they were in fact ghosts [as was he]; man-shaped stains on the brightness of the air… I noticed that the grass did not bend under their feet: even the dew drops were not disturbed.” “…the light, the grass, the trees were… made of some different substance, so much solider than things in our country.” (Chapter 2)

So it’s this world (not Heaven) that is shadowy and misty. Even the outskirts of Heaven are “super-substantial”. Our Lord Jesus Christ ascended Bodily into Heaven to prepare a place for us, bodily. “I look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the age to come. Amen.”

The Holy Mountain

To the East, “Very far away I could see what might be either a great bank of cloud or a range of mountains. Sometimes I could make out in it steep forests, far-withdrawing valleys, and even mountain cities perched on inaccessible summits. At other times it became indistinct. The height was so enormous that my waking sight could not have taken in such an object at all. Light brooded on top of it: slanting down thence it made long shadows behind every tree on the plain. There was no change and no progression as the hours passed. The promise – or threat – of sunrise rested immovably up there.” (Chapter 3)

“Long after that I saw people coming to meet us. Because they were bright I saw them while they were still very distant, and at first I did not know that they were people at all. Mile after mile they drew nearer. The earth shook under their feet… no one in that company struck me as being of any particular age…” (Chapter 3)

His guide explains: “Every one of us lives only to journey further and further into the mountains. * Every one of us has interrupted that journey and retraced immeasurable distances to come down today on the mere chance of saving some Ghosts.” (Chapter 9) – “ghosts” they have loved on earth.

-

Saint Gregory of Nyssa: “No limit would interrupt the growth in the ascent to God, since no limit to the Good can be found nor is the increasing of the desire for the Good brought to an end because it is satisfied.” (Life of Moses)

Lewis asks: “Is there really a way out of Hell [the grey town] into Heaven?” His guide explains: “If they leave that grey town behind it will not have been Hell. To any that leaves it, it is Purgatory. And perhaps ye had better not call this country Heaven. Not Deep Heaven, ye understand… Ye can call it the Valley of the Shadow of Life.”

The End

“I stood… with my back to the East and the mountain… [The face of his guide] flushed with a new light. A fern, thirty yards behind him, turned golden. The eastern side of every tree-trunk grew bright. Shadows deepened… suddenly a full chorus was poured from every branch; cocks were crowing, there was music of hounds and horns; above all this ten thousand tongues of men and woodland angels and wood itself sang. ‘It comes! It comes!’ they sang. ‘Sleepers awake! It comes, it comes, it comes!’

One dreadful glance over my shoulder I essayed – the rim of the sunrise that shoots Time dead with golden arrows and puts to flight all phantasmal shapes… ‘The morning, the morning’. I cried, ‘and I am a ghost.’ But it was too late. The light, like solid blocks, intolerable of edge and weight, came thundering upon my head.” (Chapter 14)

He awoke. It was 3 a.m. in wartime London, “the siren howling overhead.”

Next Week: Heaven in CSL’s The Chronicles of Narnia

Week After Next: A Saint of Three Continents