July 20 is the feast day of Mother Maria who died in 1945, seventy five years ago, in a Nazi gas chamber.

On February 10, 1943, she was arrested by the Gestapo at her “monastic” house in Paris. While she had been traveling, the Nazis had  arrested Yura (son of Maria and her second husband) who was carrying a letter giving evidence they had been giving refuge to Jews, and in order to protect them had provided them with false certificates of Baptism.

arrested Yura (son of Maria and her second husband) who was carrying a letter giving evidence they had been giving refuge to Jews, and in order to protect them had provided them with false certificates of Baptism.

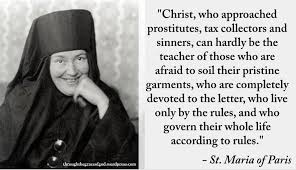

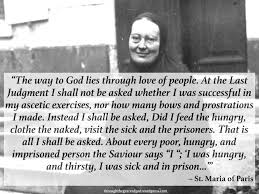

I think you already perceive that Maria was not your usual nun. Nor did she intend to be. She was professed a nun on her condition that she be free to give her life completely to the service of the poorest, the lowest, the neediest, the “least of these my brethren”. She called it “monasticism in the world.”

I’ll say just enough about her earlier life here so we can understand her and the historical context (with a few side comments of my own), and then focus on her horrifying, utterly inspiring last two years.

The best complete account of her life I’ve found is “Saint of the Open Door”, from “In Communion”, the website of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship of the Protection of the Mother of God, written in 2004 by their editor and co-secretary Jim Forest. Go to: https://incommunion.org/2004/10/18/saint-of-the-open-door/ I’m drawing much here from his article, where he identifies his sources. Google “Mother Maria of Paris” to find many other accounts of her life.

Her Life in Russia

Mother Maria Skobtsova was born in 1891 into a notable family in  Latvia, then part of the Russian Empire. Baptized Elizaveta (called “Liza”), her family soon moved to far southern Russia where she grew up in the lovely town of Anapa on the Black Sea. Right From early childhood she showed a deep concern for people.

Latvia, then part of the Russian Empire. Baptized Elizaveta (called “Liza”), her family soon moved to far southern Russia where she grew up in the lovely town of Anapa on the Black Sea. Right From early childhood she showed a deep concern for people.

Her family were devout Orthodox, as was she till when she was fourteen her father died. The shock caused her to question God. Her mother moved the family to Saint Petersburg. She was brilliant, a skilled writer, teacher and poet, and soon fell in with the crowd of radical atheistic intellectuals there. She married a man of this sort, and they had a daughter. However, she soon discovered that these radicals talked a lot about, but actually cared little about real people. Already she was beginning her return – first to Jesus, the man who truly loved and suffered for people, then to the Man Christ our God, finally to the Church. Their marriage fell apart.

Russia was soon in the throes of revolution. Liza saw that the Bolsheviks also cared much about ideology, not much about people. She joined the less ideological, more democratic party which was in power briefly in 1917. These two groups popularly were called the “White Russians” and the “Red Russians” (Bolsheviks, “Communists”). When the Bolsheviks took power, Liza returned home, barely escaping with her life, where she was elected mayor of Anapa!

The Reds murdered the Royal Family and inflicted immense suffering on people. Soon Russia was torn apart by civil war between the Red Army and the White Army. Though she despised the Bolsheviks, Liza remained as mayor. Then the White Army arrived in Anapa, figured she must therefore be a Bolshevik and arrested her.

Comment: The principle here is “If you work with our ideological enemy in any way, you must be one of them.” If this reminds you of some of American politics today, it should. If that scares you, it should.

Liza explained she was not a Bolshevik, was interested only in helping people, and was let off by a friendly judge. They fell in love and married. (One must wonder if something had already been going on between them!) But then the Reds won the civil war.

Refugees

Liza and her family fled, leaving almost everything behind – she pregnant, soon to give birth to a daughter. Finally in 1923 they settled in Paris, where there was a sizable Russian emigre community who helped them. She and her husband worked hard. A number of excellent Russian theologians were in Paris, and Liza found a spiritual home with the Russian Student Christian Movement.

Then her little daughter died. Do you know what this does to a mother? Nothing can be harder. Mothers never really recover. Nor did Liza. However, while the death of her father had caused her to turn away from God, the death of her daughter caused her to draw nearer to God. She began to feel a special call from Him to become “mother to many”.

She worked with the many Russian refugees who lived in the conditions of immigrants always, everywhere, and also she skillfully taught them. About now she and her second husband separated, for reasons not explained – but I wonder if it was because of the demands of her new calling.

Finally she became sure she should be a nun, living in poverty – but not like the nuns and monasteries she knew, who seemed so unaware that “the world is on fire”, as she put it. Communists were doing horrible things to the Russians. The world had fallen into the Great Depression. There was so much suffering. She must give herself and all she had for the poor. Her estranged husband was opposed to her becoming a nun (still hoping for reconciliation?) but their Bishop Eulogy convinced him. They received an ecclestical divorce, and a few weeks later Liza was professed as a nun, given the name Maria. This was in 1932.

give herself and all she had for the poor. Her estranged husband was opposed to her becoming a nun (still hoping for reconciliation?) but their Bishop Eulogy convinced him. They received an ecclestical divorce, and a few weeks later Liza was professed as a nun, given the name Maria. This was in 1932.

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Indeed “the world was on fire”.

Mother Maria

A nun? But such a nun! Here was how Metropolitan-to-be Anthony Bloom described his first encounter with her: “She was a very unusual nun in her behavior and her manners. I was simply staggered when I saw her for the first time in monastic clothes. I was walking along the Boulevard Montparnasse and I saw: in front of a café, on the pavement, there was a table, on the table was a glass of beer and behind the glass was sitting a Russian nun in full monastic robes. I looked at her and decided that I would never go near that woman” To explain, he added, “I was young then and held extreme views.”

Have you known people who somehow just drew people and their problems to themselves? Our late Deacon John was one of those. My late mother in law was another. Once in a department store a complete stranger poured out her whole life to her while they were waiting in the check out line! Mother Maria was like that. People of all sorts naturally gravitated towards her, and she welcome them all.

She founded a monastic house on Rue de Lourmel in Paris. But again not quite your usual monastery. Right This was a house of refuge for the needy of all sorts. She turned away no one. They shared meals. There was a common prayer life of a sort, but if the doorbell rang she would interrupt the prayers and answer it. It might be a needy person who must not be turned away. Two other nuns joined her, sympathetic to her work, but then left for lack of a more consistent prayer life. And so things continued until…

She founded a monastic house on Rue de Lourmel in Paris. But again not quite your usual monastery. Right This was a house of refuge for the needy of all sorts. She turned away no one. They shared meals. There was a common prayer life of a sort, but if the doorbell rang she would interrupt the prayers and answer it. It might be a needy person who must not be turned away. Two other nuns joined her, sympathetic to her work, but then left for lack of a more consistent prayer life. And so things continued until…

The Last Years

I’m sorry to include some of the images below. They’re horrifying. I find them very hard to handle.

I’m also not sorry.

Let me tell you a story.

In 1985 our litle family went to Europe. Among other things we visited “Uncle Hermann” in Frankfurt who took us on a tour of Olnhausen sites. I’m accustomed to Germans on that side of my family. Also, our part of Wisconsin has very many people of German origin. Everywhere we went German people were extremely friendly and welcoming. They spoke German, of course, but their inflections, their faces and facial expressions, everything about them seemed so much like people I knew at home. Then on the wall of the church in Olnhausen village I saw an old picture of young parish men in their Nazi “brown shirts”. Uncle Hermann was embarrassed and apologized for it. I know Germany today is a far different place. They seem to have learned well from their nightmare. But I thought: If it could happen among these kindly intelligent people, so much like the people I knew at home, where could it not happen…? Beware, brothers and sisters. Beware.

What follows here in italics is taken directly from the article by Jim Forest, to whom I am deeply grateful.

Paris fell on the 14th of June. France capitulated a week later. With defeat came greater poverty and hunger for many people. Local authorities in Paris declared the house at rue Lourmel an official food distribution point — Cantine Municipale No. 9. Here volunteers sold at cost price whatever food Mother Maria had bought that morning at Les Halles.

Paris was now a great prison. “There is the dry clatter of iron, steel and brass,” wrote Mother Maria. “Order is all.” Russian refugees were among the particular targets of the occupiers. In June 1941, a thousand were arrested, including several close friends and collaborators of Mother Maria and Father Dimitri. An aid project for prisoners and their dependents was soon launched by Mother Maria.

Early in 1942, their registration now underway, Jews began to knock on the door at Rue de Lourmel asking Father Dimitri [their priest] if he would issue baptismal certificates to them. The answer was always yes. The names of those “baptized” were also duly recorded in his parish register in case there was any cross-checking by the police or Gestapo, as indeed did happen. Father Dimitri was  convinced that in such a situation Christ would do the same…

convinced that in such a situation Christ would do the same…

When the Nazis issued special identity cards for those of Russian origin living in France, with Jews being specially identified, Mother Maria and Father Dimitri refused to comply, though they were warned that those who failed to register would be regarded as citizens of the USSR — enemy aliens — and be punished accordingly.

In March 1942, the order came from Berlin that the yellow star Jews must be worn by Jews in all the occupied countries. The order came into force in France in June.

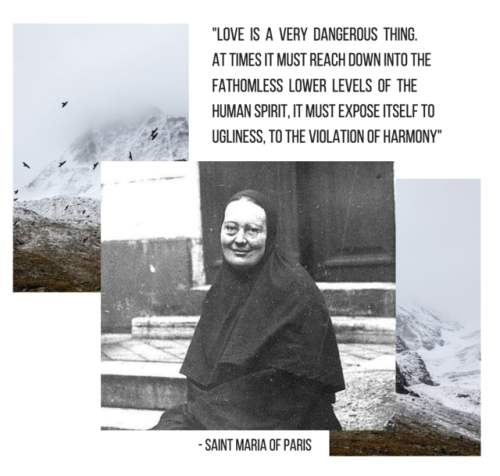

“Mother Maria, prisoner 19,263, was sent in a sealed cattle truck from Compiegne to the Ravensbruck camp in Germany, where she endured for two years, an achievement in part explained by her long experience of ascetic life. She was assigned to Block 27 in the large camp’s  southwest corner. Not far away was Block 31, full of Russian prisoners, many of whom she managed to befriend.

southwest corner. Not far away was Block 31, full of Russian prisoners, many of whom she managed to befriend.

Unable to correspond with friends, little testimony in her own words has come down to us, but prisoners who survived the war remembered her. One of them, Solange Perichon, recalls:

“She was never downcast, never. She never complained…. She was full of good cheer, really good cheer. We had roll calls which lasted a great deal of time. We were woken at three in the morning and we had to s tand out in the open in the middle of winter until the barracks [population] was counted. She took all this calmly and she would say, ‘Well that’s that. Yet another day completed. And tomorrow it will be the same all over again. But one fine day the time will come for all of this to end.’ … She was on good terms with everyone. Anyone in the block, no matter who it was, knew her on equal terms. She was the kind of person who made no distinction between people [whether they] held

tand out in the open in the middle of winter until the barracks [population] was counted. She took all this calmly and she would say, ‘Well that’s that. Yet another day completed. And tomorrow it will be the same all over again. But one fine day the time will come for all of this to end.’ … She was on good terms with everyone. Anyone in the block, no matter who it was, knew her on equal terms. She was the kind of person who made no distinction between people [whether they] held

extremely progressive political views [or had] religious beliefs radically different than her own. She allowed nothing of secondary importance to impede her contact with people.”

Another prisoner, Rosane Lascroux, recalled:

“She exercised an enormous influence on us all. No matter what our nationality, age, political convictions — this had no significance whatever. Mother Maria was adored by all. The younger prisoners gained particularly from her concern. She took us under her wing. We were cut off from our families, and somehow she provided us with a family.”

In a memoir, Jacqueline Pery stressed the importance of the talks Mother Maria gave and the discussion groups she led:

“She used to organize real discussion circles … and I had the good fortune to participate in them. Here was an oasis at the end of the day. She would tell us about her social work, about how she conceived the reconciliation of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. We would question her about the history of Russia, about its future, about Communism, about her frequent contacts with young women from the Soviet army with whom she liked to surround herself. These discussion, whatever their subject matter, provided an escape from the hell in which we lived. They allowed us to restore our depleted morale, they rekindled in us the flame of thought, which barely flickered beneath the heavy burden of horror.”

Often, Pery wrote, she would refer to passages from the New Testament: “Together we would provide a commentary on the texts and then meditate on them. Often we would conclude with Compline… This period seemed a paradise to us.”

Often, Pery wrote, she would refer to passages from the New Testament: “Together we would provide a commentary on the texts and then meditate on them. Often we would conclude with Compline… This period seemed a paradise to us.”

Yet, as was recalled by another prisoner, Sophia Nosovich, Mother Maria “never preached but rather discussed religion simply with those who sought it, causing them to understand it and to exercise their minds, not merely their feelings. Whatever and however she could, she would sustain the as yet incompletely extinguished flame of humanity, no matter what form it took.”

The same former prisoner wrote that “it was not submissiveness which gave [Mother Maria] strength to bear the suffering, but the integrity and wealth of her interior life.”

And all this happened in what Mother Maria described not as a prison but as hell itself, nothing less, a bestial place in which obscenity, contempt and hatred were normal and where hunger, illness and death were daily events. In such a climate, many opted for the numbing of all feeling and withdrawal as a survival strategy while others, in their despair, looked forward only to death.

And all this happened in what Mother Maria described not as a prison but as hell itself, nothing less, a bestial place in which obscenity, contempt and hatred were normal and where hunger, illness and death were daily events. In such a climate, many opted for the numbing of all feeling and withdrawal as a survival strategy while others, in their despair, looked forward only to death.

“I once said to Mother Maria,” wrote Sophia Nosovich, “that it was more than a question of my ceasing to feel anything whatsoever. My very thought processes were numbed and had ground to a halt. ‘No, no,’ Mother Maria responded, ‘whatever you do, continue to think. In the conflict with doubt, cast your thought wider and deeper. Let it transcend the conditions and the limitations of this earth’.”

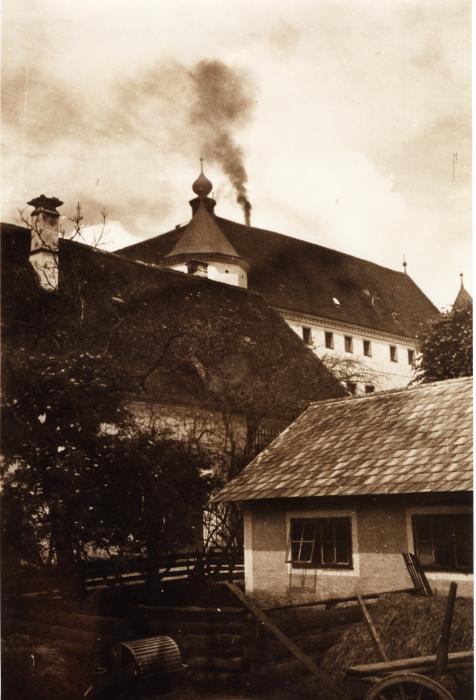

One prisoner even recalled how Mother Maria had used the ever-smoking chimneys of the camps several crematoria as a metaphor of  hope rather than being seen as the only exit point from the camp. “But it is only here, immediately above the chimneys, that the billows of smoke are oppressive,” Mother Maria said. “When they rise higher, they turn into light clouds before being dispersed in limitless space. In the same way, our souls, once they have torn themselves away from this sinful earth, move by means of an effortless unearthly flight into eternity, where there is life full of joy.” [Left: Auschwitz)

hope rather than being seen as the only exit point from the camp. “But it is only here, immediately above the chimneys, that the billows of smoke are oppressive,” Mother Maria said. “When they rise higher, they turn into light clouds before being dispersed in limitless space. In the same way, our souls, once they have torn themselves away from this sinful earth, move by means of an effortless unearthly flight into eternity, where there is life full of joy.” [Left: Auschwitz)

Anticipating her own exit point from the camp might be via the crematoria chimneys, she asked a fellow prisoner whom she hoped would survive to memorize a message to be given at last to Father Sergei Bulgakov, Metropolitan Eulogy and her mother: “My state at present is such that I completely accept suffering in the knowledge that this is how things ought to be for me, and if I am to die, I see this as a blessing from on high.”

In a postcard she was allowed to send friends in Paris in the fall of 1944, she said she remained strong and healthy but had “altogether become an old woman.”

Her work in the camp varied. There was a period when she was part of a team of women dragging a heavy iron roller about the roads and pathways of the camp for 12 hours a day. In another period she worked in a knitwear workshop.

Her work in the camp varied. There was a period when she was part of a team of women dragging a heavy iron roller about the roads and pathways of the camp for 12 hours a day. In another period she worked in a knitwear workshop.

Her legs began to give way. At roll call another prisoner, Inna Webster, would act as her crutches. As her health declined, friends no longer allowed her to give away portions of her own food, as she had done in the past to help keep others alive.

Friends who survived recalled that Mother Maria wrote two poems while at Ravensbruck, but sadly neither survive. However a kerchief she embroidered for Rosane Lascroux, made with a needle and thread

stolen from the tailoring workshop at last came out of the camp intact. In the style of the medieval Bayeux Tapestry, it was a depiction of the Allies’ Normandy Landing in June 1944. Her final embroidered icon, purchased with the price of her precious bread ration, was of the Mother of God holding the infant Jesus, her child already marked with the wounds of the cross.

With the Red Army approaching from the East, the concentration camp administrators further reduced food rations while greatly increasing the population of each block from 800 to 2,500. “People slept three to a bunk,” a survivor recalls. “Lice devoured us. Typhus and dysentery became a common scourge and decimated our ranks.”

By March 1945, Mother Maria’s condition was critical. She had to lie down between roll calls and hardly spoke. Her face, as Jacqueline Pery recalled, “revealed intense inner suffering. Already it bore the marks of death. Nevertheless Mother Maria made no complaint. She kept her eyes closed and seemed to be in a state of continual prayer. This was, I think, her Garden of Gethsemane.”

In November-December 1944, she accepted a pink card that was freely issued to any prisoner who wished to be excused from labor because of age or ill health. On January all who had received such cards were rounded up and transferred to what was called the Jugendlager — the “youth camp” — where the camp authorities said each person would have her own bed and abundant food. Mother Maria’s transfer was on January 31. Here the food ration was further reduced and the hours spent standing for roll calls increased. Though it was mid-winter, blankets, coats and jackets were confiscated, and then even shoes and stockings. The death rate was at least fifty per day. Next all medical supplies were withdrawn. Those who still persisted in surviving now faced death by shootings and gas, the latter made possible by the construction of a gas chamber in March 1945. In this 150 were executed per day.

It is astonishing that Mother Maria lasted five weeks in the “youth camp,” and was finally sent back to the Jugendlager to the main camp on March 3. Though emaciated and infested with lice, with her eyes festering, she began to think she might actually live to return to Paris, or even go back to Russia.

That same month the camp commander received an order from Reichsfuhrer Himmler that anyone who could no longer walk should be killed. While such orders had been anticipated and many already killed, the decree accelerated the process. With the help of Inna Webster and others to lean on, Mother Maria managed to continue standing at roll calls, but this became far more difficult when groups of prisoners were ordered into ranks of five for purposes of selecting those to be killed that day. Within her block, Mother Maria was sometimes hidden in a small space between roof and ceiling in expectation of raids in which additional “selections” were made. On the 30th of March Mother Maria was selected for the gas chambers — Good Friday as it happened. She entered eternal life the following day. The shellfire of the approaching Red Army could be heard in the distance.

Accounts are at odds about what happened. According to one, she was simply one of the many selected for death that day. According to another, she took the place of another prisoner, a Jew, who had been chosen. Her friend Jacqueline Pery wrote afterward:

“It is very possible that [Mother Maria] took the place of a frantic companion. It would have been entirely in keeping with her generous life. In any case she offered herself consciously to the holocaust … thus assisting each one of us to accept the cross …. She radiated the peace of God and communicated it to us.”

Holy Mother Maria

![]() On January 18, 2004, Mother Maria was formally recognized as a saint by the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, along with her son Yuri, her priest Father Dimitri Klépinin and her close friend and collaborator Ilya Fondaminsky, who also died in the same way.

On January 18, 2004, Mother Maria was formally recognized as a saint by the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, along with her son Yuri, her priest Father Dimitri Klépinin and her close friend and collaborator Ilya Fondaminsky, who also died in the same way.

Have you heard the terms “red martyr” and “green martyr”? “Martyr” μαρτύριον originally meant simply “witness”, someone who witnessed to Christ. In the early Church so many who witnessed to Christ died for Him, that the word took on its popular meaning, as we now use it. A “red martyr” literally dies for Christ. A “green martyr” gives himself or herself totally in witness to Christ in a way beyond ordinary human power. Mother Maria was both a “green martyr” and a “red martyr”.

![]() So far as I know no miracles have been attributed to her. (Please correct me if I’m wrong.) But the last years of her life were surely miraculous, beyond any human power that we understand. Or to put another way: Can you or I, in our condition, even imagine doing what Mother Maria did? You see.

So far as I know no miracles have been attributed to her. (Please correct me if I’m wrong.) But the last years of her life were surely miraculous, beyond any human power that we understand. Or to put another way: Can you or I, in our condition, even imagine doing what Mother Maria did? You see.

Holy Mother Maria, pray to Christ our God to save our souls.

Next Week: Saint Panteleimon, a physician who didn’t charge his patients

Week after next: A slapstick story in the Gospels?

The 20th century saints of Orthodoxy are such a powerful witness to the faith. The martyrs for sure, but the hesychasts as well. I bought books about Sts Silouan and Porphyrios (from a Catholic bookstore) because of their photographs on the back covers: I saw something in their faces. Mother Maria has one of those faces.

All the poor ignorant young college-age fools out marching don’t know about Mother Maria, or John of San Francisco, or Herman. How they TRULY served and TRULY evangelized. Or how the Russians, Romanians, Greeks and Syrians SUFFERED under Marxism and Mohammedism.

Do we need to find just one person from each parish to give a short talk or power point slide show at every local school or college. Because the kids need to know the truth. As Seraphim Rose said, “It’s later than we think.”

Thanks Father.

I couldn’t agree more with what you say about Orthodoxy’s great 20th century witnesses to the Faith. Our people need to know more about them. However as for calling people “fools”, see Matthew 5:22.

Here’s a very relevant article from the Greek Archdiocese: https://www.goarch.org/-/orthodox-christianity-systemic-racism-wrong-side-of-history

I didn’t mean to sound critical of protests against racism. (I’m a musician. Racism, especially directed at Black Americans, isn’t a possibility for me. All styles of American popular music, even Country & Western, are built on the foundation provided by Black artists. Hank Williams is a good example.)

I was critical of the college-age mobs in terms of their obvious, to me anyway, Bolshevism. When given a chance to speak, their ignorance and naivety about the bloody history of Communism is frightening. That’s what I was speaking to.

I see nothing of the spirit of Rev King in the mobs. His marches were Christian and American and stirred hearts and minds. I don’t see that with the current movement. I see anti-Christian, anti-American spectacles designed to stir up the passions and emotions.

The official BLM ® written statements are Marxist. For the Greek Archbishop to stand next to that particular group, it puts him not in the company of Iakovos and MLK, but rather in the company of the Soviet “Living Church” or the Chinese National Catholic Church. Someone at the Archdiocese should have done their homework before sending the bishop in front of the cameras.

Nobody else has responded, so I’ll give it a shot.

Yes, the Black Lives Matter statements favor a number of things we Orthodox certainly don’t endorse, including Marxism. I think this is misleading and compromises the purpose expressed in their title which concerns only “black lives”.

However I have questions, the first two addressed to you:

1) Are you suggesting that Black Lives Matter are Bolshevik totalitarians (which was not true Marxism)? that those who protest today favor Soviet Communism?

2) Why do you use the code word “mobs” for today’s protesters? Do you think most of them are thugs? The media tend to publicize the extremes, but it looks to me that most of them (for example here in the Milwaukee area) are entirely peaceful. Back in the ‘60s (despite some Christian leadership) there was far more chaos and destruction in our cities than there is now. I remember it.

3) Where today are our Christian leaders taking the lead in the fight against injustice and cruelty? Surely traditional Christins should be at the forefront trying to “defend the poor and fatherless, do justice to the afflicted and needy, deliver the poor and needy, free them from the hand of the wicked”. Back in the ‘60s Christians (Martin Luther King and others) were often there. Today not so much. No wonder secularists are often taking over.

4) When traditional Christian leaders today do speak out for justice (for example the recent excellent statement by our American Orthodox Bishops) am I correct in thinking that they are largely ignored in the Church?

5) Is the big problem that Christianity is now declining rapidly in America, both in numbers and (with one exception) in influence? Why are many of our young people falling away entirely from religion?

1) Yes. When a BLM spokesman says We’re coming after White Jesus and his European Mother, yes. When even in Europe, icons (Holland) and statues are spray painted BLM, yes. I think the radical left is using the protests to advance their cause and make converts.

2) Mobs. When at 4:30pm I watch local Philly news with cop cars burned, and pharmacies and liquor stores looted, in broad daylight, with dozens, maybe hundreds of participants involved, I call that a mob. And plenty of cell phone footage on line if people want to see it. Cuz its not always explicit on national news.

3 & 4) My sense is the racial injustice is over-hyped. Is it really as bad now as, say, 1960? I don’t see White Only or Colored Only signs. Is America really so full of bigots when we elected a black man President for two terms? I see black n white children playing together every day. I see interracial marriages everywhere, even in small town “redneck” America.

5) The decline is partly materialism, partly the apostasy of the baby boomers not handing on the faith, post modern indifference to objective truth, mushy ecumenism that sez all religions are the same, poor examples from believers, ignorance of Orthodoxy vs exposure to Calvinism and heretical Christianity, bad history (Islam peaceful but Christianity violent) etc. And the noise of a media saturated world with no silence or quiet. We’re too distracted to even notice how sick our collective soul is.

In brief, without Orthodox Christianity, lived, something is gonna fill the void. And that very well might be Communism or Islam. It’s happened before.

It was listening to protesters, in their own words, that informed my comments. And watching Dr Zhivago again. The Bolshies were obsessed with making things more just.

I’m enjoying this dialog, and I hope you are, too.

1) He was trying to get rid of WHITE Jesus and Mary. I agree. They were Middle Eastern Semites with darkish skin. I have an old western “Christus Rex” hanging on my wall, which I love, but He looks like He came from Sweden or somewhere. It’s sacrilege to deface holy statues and icons, but is this common?

2) Cell phones also pick up the extremes. Who wants to look at videos of all the moms and dads and clergy and ordinary folks in the protests. Our next door neighbor (an administrator at a Catholic university, with a big Amerivcan flag always flying at their house) marched not for Marxism but for racial justice. I can’t walk much any more because of my neuropathy. Who’s trying to take advantage? Is it only the radical left or are there other more subtle possibilities?

3) and 4) Yes, great progress has been made in human relations, actually. A black President. White Alabama State Patrolmen saluting John Lewis’ coffin. Brilliant women on radio and TV. I never imagined I would see such things. But ordinary black folks just want to be ordinary human beings. Once they were treated as sub-human; now it’s as mostly human. Sufficient?

5) Amen. Except: What are the dangers in American today? God save us from Bolsheviks, and fascists and dictators and a whole bunch of people, all of whom always say they are doing it for our good.

I like talking with you.

Thanks. I thought I was getting on your nerves.

My main point is that Orthodox Christians, especially “cradles”, need to be the canaries in the coal mine regarding the growth of both Marxism and Islam. And we have the dead bodies and burned villages to make the point.

Our young people don’t know that history. (Or the history of Islamic imposed slavery. For example, the Slavs taken by Muslims to Spain. Doesn’t the English word “slave” derive from “Slav”?) And weren’t the Antiochian & Melkite churches in America mostly founded by folks fleeing persecution? In my part of PA they were.

The protests that started over George Floyd were hijacked. I know cops can be bullies. We had 2 unarmed (white, if it matters) local guys, separate incidents, shot dead through the windshield of their stopped and surrounded cars, 10-15 rounds, by cops. But I’m not bombing the courthouse or demanding the abolition of police.

I met a white racist cop in Boston. Probably cuz the only black people he knew were pimps and drug dealers he arrested nightly in Chinatown. I was with black friends in a bar, when we had to chase out Nazi skinheads looking for trouble. And I’ve had rocks and bottles thrown at me, and been sucker-punched by black kids, simply for walking down the street. So, I know racism first hand.

But I see media and academia turning a naive blind eye, in history and current events, that demonzes Christian belief, but gives a free pass to anti-Christian deeds of violence. And where’s the justice in that?

I think one of the values of sharing a solid Orthodox foundation is that people who disagree can talk with each other without losing their cool, and in the process come to understand and learn from each other. Years ago there were two men from Saint Nicholas, one an old time Milwaukee socialist (definitely not Bolshevik!) and the other a far right wing conservative. At Sunday coffee hour they would argue away quietly. Then they’d say “Have a good day. See you next Sunday”, smile, shake hands and go home. They remained good friends.

I think you and I are much closer in principle and desire than we sounded at first. We’re just coming at it from different directions. I agree especially with what you said about the media and academia. Why don’t they mention all the good Christianity has done? It’s interesting that the BBC (in secular England) has a couple or three drama series about priests which make them out to be basically good guys. Their Father Brown (RC) is brilliant. But not over here, and I have an explanation for this.

Regarding persecution by Muslims, I’d add a “yes…and”. In my Archdiocese we have many Palestinians driven off their lands not by Muslims but by Israelis. They remain on good terms with their fellow Muslim Palestinians who have suffered the same fate.