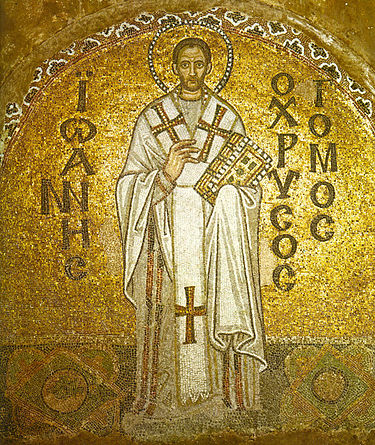

On January 27, 438, the incorrupt body of Our Holy Father  John Chrysostom arrived in Constantinople – “translated” (moved) from Armenia where he had been banished and where he had died 31 years earlier. His relics were received with honor into the imperial city where once he had been Patriarch.

John Chrysostom arrived in Constantinople – “translated” (moved) from Armenia where he had been banished and where he had died 31 years earlier. His relics were received with honor into the imperial city where once he had been Patriarch.

The story of John Chrysostom

I am no historian, so please correct me if I have anything wrong, and of course in this short article much is omitted. I have collected this story over the years for my parish use, from various sources which I’ve now forgotten, so if I have failed to attribute anyone please forgive me.

John had come from the great city of the East, Antioch of Syria, born in 347 to a notable family. His father Secundus was Imperial Consul for the East, appointed by Constantine the Great. After he died John’s mother Anthousa made sure their son had the finest education. He studied in Athens under the greatest scholars of the time. Young John was brilliant, so good at rhetoric and philosophy that the great teacher Livanius asked him to stay as his assistant and succeed him at his Academy. But John had also studied law, and he returned to Antioch to become (what we now call) a public defender.

John had come from the great city of the East, Antioch of Syria, born in 347 to a notable family. His father Secundus was Imperial Consul for the East, appointed by Constantine the Great. After he died John’s mother Anthousa made sure their son had the finest education. He studied in Athens under the greatest scholars of the time. Young John was brilliant, so good at rhetoric and philosophy that the great teacher Livanius asked him to stay as his assistant and succeed him at his Academy. But John had also studied law, and he returned to Antioch to become (what we now call) a public defender.

In adulthood he was baptized and became a Christian and then, after his mother’s death, a monk. He spent four years at a monastery in Antioch, then got permission to become a hermit in a cave outside the city. There he nearly ruined his health through extreme fasting – a sign of what some would describe as great devotion, others might call over-enthusiasm. I think it was both. John was never one to give up easily or to do things half way. This would get him into more trouble later. It also made him a saint. His bishop finally ordered him to return to the monastery. His health never fully recovered.

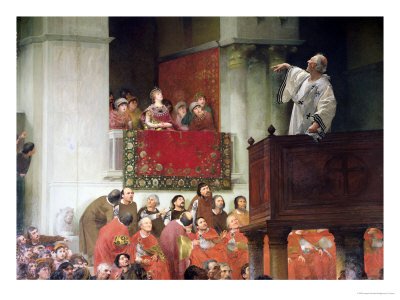

John Chrysostom’s Preaching

He was ordained Deacon, then Priest and began to preach. This was how he got the nickname Chrysostomos, Χρυσόστομος, literally “golden mouth”. “Golden tongued” we would probably say today. His sermons were so good that he filled the church not only with Christians but even with pagans and Jews. He was probably the best Bible preacher in history. Many of his sermons are translated into English and still in print – and now online. He was steadfastly Orthodox, with no compromises. He followed the Antiochian school of interpretation – literal, practical.

His usual style was to take the Scripture passage appointed for the day and go through it verse by verse. By today’s standards, his sermons were very long. Most of us preachers would likely bore our people to death this way. Not John. Oh, the depth of his interpretation and how masterfully and how fervently he presented the Scriptures! When he really got going, people said he could make the rocks cry.

Do you want a sample? Here are two quotes from his Paschal Sermon, always read just before the beginning of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom at Pascha.

Do you want a sample? Here are two quotes from his Paschal Sermon, always read just before the beginning of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom at Pascha.

“Let all partake of the feast of faith. Let all receive the riches of goodness. Let no one lament their poverty, for the universal kingdom has been revealed. Let no one mourn their transgressions, for pardon has dawned from the grave. Let no one fear death, for the Saviour’s death has set us free… O Death, where is your sting? O Hell, where is your victory? Christ is risen, and you are overthrown. Christ is risen, and the demons are fallen. Christ is risen, and the angels rejoice. Christ is risen, and life reigns. Christ is risen, and not one dead remains in the grave. For Christ, being risen from the dead, is become the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep. To Him be glory and dominion unto ages of ages. Amen.” To hear this read in church is thrilling – there is no other word for it. *

- Read the full Paschal sermon (it is not long) at https://oca.org/fs/sermons/the-paschal-sermon

In 387, the people of Antioch rebelled against high imperial taxes and injudiciously destroyed many statues of the Emperor. This was a capital offense, and soldiers began to execute great numbers of citizens. The Patriarch of Antioch went to Constantinople to beg for mercy. Meanwhile Father John stayed in the city and preached a series of powerful sermons “On the Statues”, urging people to cool off and trust in God instead of in violence. The Emperor relented. John and the Patriarch had saved Antioch from destruction.

Patriarch John Chrysostom

John became so famous that in the year 398 he was elected Patriarch of Constantinople. He did not want it. Perhaps he suspected what would come of it. He fled the city. Some accounts say the authorities captured him and hauled him off unwillingly! However it happened, in the end he gave in and accepted the throne at Hagia Sophia. (This was the old Hagia Sophia, not the present one which was erected by Justinian two centuries later.)

John was a great theologian, a brilliant preacher. What would he be like as a Patriarch? This soon became clear, all too clear in some peoples’ opinion.

His predecessor had been lax about clergy discipline. John was strict. Constantinople was full of bishops and other clergy from the provinces who hung around, ostensibly on business but actually because the hinterlands bored them. They preferred the excitement of “The City”, as it was called. John ordered them to go home and get to work. He was no less tough with lax clergy of Constantinople. Many of them were not impressed. They had other ideas. John preached: “The road to Hell is paved with the bones of priests and monks, and the skulls of bishops are the lamp posts that light the path.” (!) Oh, help.

But the Patriarch himself set the example. John had been tough on himself all his life, and he expected no less of his clergy. Hierarchs normally lived in elegance, throwing great banquets for wealthy and powerful dignitaries. John cared for none of that. He had always lived the ascetic life, and when anyone came to visit him, no matter who they were, he gave them monastic fare to eat.

John was a great Liturgist. In those Patristic times, forms of the Divine Liturgy were still undergoing development. He took the current Liturgy of Constantinople, revised it greatly adding major elements from the Antiochian (“West Syrian”) practice which he knew, and developed the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, which now 1700 years later remains the normal Sunday Liturgy of about 250 million Eastern Orthodox Christians. (Details of his Liturgy, as we know it, were finalized in later centuries.)

John preached daily. Daily the church was filled. Wonderful sermons on everything imaginable: Christ, the Trinity, the priesthood, the sacraments, marriage and family, repentance and forgiveness, and much more. Not surprisingly, he was subject sometimes to the prejudices of the day, as who isn’t? But he was especially concerned for the moral life. He railed against women who came to church dressed as if they were going dancing or to the theater. He chastized men who treated their wives like  chattel possessions. He was critical of games at the Hippodrome, for Constantinople was a big sports and party town, and John thought these distracted people from more important things, and besides people wasted great sums of money gambling, when it could and should have been given to the poor.

chattel possessions. He was critical of games at the Hippodrome, for Constantinople was a big sports and party town, and John thought these distracted people from more important things, and besides people wasted great sums of money gambling, when it could and should have been given to the poor.

You can find many short quotations from John Chrysostom at: https://www.azquotes.com/quote/876649 They are down to earth, humane, inspiriting, challenging. If you read only a few of them you will be edified. I guarantee.

John Chrysostom on Social Injustice

Patriarch John was offended by the social inequality he saw: the royalty and the wealthy living in exorbitant luxury, while around them were widows, orphans and paupers in abject poverty. He preached sermon after sermon railing against inequality and social injustice. In this present time of glorification of wealth and of great social inequality, we need to hear John Chrysostom. Listen to just a little of what he said:

“Not to share our own wealth with the poor is theft from the poor and deprivation of their means of life; we do not possess our own wealth, but theirs.”

“What good is it if the Eucharistic table is overloaded with golden chalices when your brother is dying of hunger. Start by satisfying his hunger and then with what is left you may adorn the altar as well.”

“There is harm not only in trying to gain wealth but also in excessive concern with even the most necessary things. It is not enough to despise wealth, but you must also feed the poor and, more importantly, you must follow Christ.”

“If you would rise, shun luxury, for luxury lowers and degrades.”

“If you would rise, shun luxury, for luxury lowers and degrades.”

“How do you think you obey Christ’s commandments, when you spend your time collecting interest, piling up loans, buying slaves like livestock and merging business with business? … Upon this you heap injustice, taking possession of [peoples’] lands and houses, and multiplying poverty and hunger… In the matter of piety, poverty serves us better than wealth, and work better than idleness, especially since wealth becomes an obstacle even for those who do not devote themselves to it. [God gives wealth] not for you to waste on prostitutes, drink, fancy food, expensive clothes and all the other kinds of indolence but for you to distribute to those in need. [Excessive wealth] is theft, not because it was stolen as a means of gaining wealth, but because keeping it is to deprive others of their needs. If you have two pairs of shoes, one belongs to the poor.”

“If you cannot find Christ in the beggar at the church door you will not find him in the chalice.”

You can imagine how his words were heard by the wealthy. Imagine how they would be heard today!

John Chrysostom Exiled

The common people loved all this but, but among the powerful this eccentric Archbishop from the hinterlands did not win many friends. The Empress Eudokia utterly despised him. Finally a group of displeased clergy accused him of restoring some heretical clergy. It wasn’t true, but the Emperor, urged on by his Empress, agreed to have him banished. John had been taken only a few miles outside the city when the people heard the news, and rioting began. The Emperor decided it wasn’t worth it. He brought John back. When he entered the City the crowds were so great it took him hours to move the short distance to his residence.

The Empress Eudoxia was now John’s enemy, and when she came to church he preached against her. He had good reason, for she had now a great statue erected to herself at the Hippodrome. The Empress and her courtiers regularly arrived late for Divine Liturgy (is this how the Orthodox custom began?!) and went out of their way to make a great commotion coming in. John criticized them for this publicly.

So the Empress decided to score another point against John (sounds like modern politics): she had a statue of herself erected opposite Hagia Sophia so that as Archbishop John went out  the first thing he would see would be another great statue of “his enemy”. John exploded: “Again Herodias dances”, he cried in a sermon. “Again she rages, again she demands the head of John.”

the first thing he would see would be another great statue of “his enemy”. John exploded: “Again Herodias dances”, he cried in a sermon. “Again she rages, again she demands the head of John.”

As I said, John Chrysostom was not one to do things half way. Could he have handled this better? Could he have been a bit more subtle? Could he have avoided this personal feud with the Empress? I think maybe so, but then I wasn’t there. Maybe there was no other way to deal with Eudokia. By now the Emperor had “had it”. Again he banished John. John gave orders to his clergy to obey his successor. As he was taken off in custody, his guards rode on horseback but Patriarch John, just to score another point, walked. This time there was even greater rioting: the Senate Building and other public buildings were burnt to the ground, including old Hagia Sophia. (I do hope the statues of the Empress went down too, but the accounts don’t say.) This time the Emperor brought in the troops and suppressed the rioters. There were many casualties. This time he did not relent.

The rest of the story isn’t long. John was exiled into the Caucusus in Armenia. His health failed. By letter he kept in contact with friends in Constantinople. When the Emperor found out about it, he gave orders to take him even further away into the mountains – this as winter was coming on. Along the way one night he dreamt of the Martyr Basiliscos of Comana, the village through which they were passing, calling to him. Next morning John awoke, said “Glory to God for all things!”, and he died. It was November 13, 407.

Saint John Chrysostom

If John was perhaps overly strict and overly stubborn, his motivation was never personal gain. There was nothing he wanted for himself. He never even wanted to be Patriarch. And he never resisted exile. All he wanted was that the Gospel be preached and that the Church stand strong for the people, the poor and needy, against all who would use their power and wealth, and especially those who would use the Church, for their own personal interests.

It’s the same battle the Church has fought in every age. Do we stand for the Gospel of Jesus Christ, for the teachings of  Jesus Christ, for Jesus Christ himself and the Orthodox Faith – or do we “kowtow” to the powers that be?

Jesus Christ, for Jesus Christ himself and the Orthodox Faith – or do we “kowtow” to the powers that be?

Chrysostom was on the right side. His biographer wrote: “Because of the rectitude of his life he was free from anxiety about the future, and the simplicity of his character rendered him open and ingenuous. Nevertheless the liberty of speech he allowed himself was offensive to many In his public teaching. The great end he proposed was the reformation of the morals of his hearers… In private people often said he was haughty and assuming; this was because they did not know him.”

Perhaps even before his death he was called Saint John Chrysostom.

The Return of Saint John Chrysostom

The Emperor and Empress were rid of this holy troublemaker, but the people of Constantinople did not forget John Chrysostom. Time passed, thirty years. The old Emperor and Empress now also were dead. A new Patriarch Proclus started a popular movement to vindicate John’s memory. The new Emperor Theodosios, son of Empress Eudokia, agreed, and he wrote a letter to John. Some say the Patriarch himself took to Armenia and read it before his relics, begging him to come home. So the incorrupt body of Saint John Chrysostom was brought back to the great City Constantinople. Huge crowds lined the streets. There had been healings from his relics in Armenia, and now there were more.

On January 27, 438, John’s body was carried in procession into the temporary Patriarchal Church of the Holy Apostles (old Hagia Sophia, remember, had been burnt down in the riot) and placed before the royal doors. Emperor Theodosios stood before it and in the name of his mother who had persecuted him, begged John’s forgiveness.

Now, maybe this is just a story. I don’t know. I wasn’t there. But it is said that someone cried out from the crowd: “Patriarch John, return to your throne”. So they carried his body up and placed it for one last time in the Patriarchal throne. And there were those present who swore that they then heard his voice from the throne just as they had heard it thirty years before: “Eirene Pasi. Εἰρήνη πᾶσι. Peace be to all.”

Next Week: Abortion

Week after Next: Pre-Lent – how the Church prepares us for the Great Fast

Wonderfully written piece on St. John Chrysostom!

As the saying goes, “it takes all kinds”. Sounds like St. John won the award for the fiery kind of preaching. A golden mouth, with salt!

That Paschal sermon… oh when I hear the fervor in his words, in celebration of this great Feast, the pentecostal in me wants to rise up and shout 🙂

St John has a heart for God. And what a supreme gift he gives us…the Divine Liturgy.

Thank God He gives us “all kinds”. The beauty of diversity.

Thank you St. John Chrysostom!

And thank you Fr Bill. Enjoying your posts. (video’s and links too!)