The Fragmenting of Protestantism

Now… if you have no acquaintance with Protestantism and probably even if you have, prepare to be confused.

From early times there have been followers of Christ outside the Church – Arians, for example, were quite numerous, as Protestants are today. Then came the great division between East and West. The Protestant Reformation led to several separate denominations. But nothing like this! Beginning about the turn of the 20th century Protestantism began to splinter.

How many Protestant denominations are there today? If we could count every independent congregation in the world, there are likely thousands. In the United States there are probably more than 200 genuine denominations – that is, organized Protestant groups with at least a few congregations. Even these are hard to identify. Here in Milwaukee, Elmbrook Church, a large independent church in a west suburb, has planted 9 more “Brook” churches in southeast Wisconsin. (We should grow so fast…) Are the Brooks now a denomination? Who’s to say?

Few Protestants seem to feel that having a gazillion denominations is a big problem. But it is! It is! On Holy Thursday night Our Lord  Jesus prayed “that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in us, that the world may believe that You sent Me.” John 17:21 How is a seeker to know what true Christianity really is? For most people it’s now “cafeteria style” Christianity. “Ooh, I like this dish. I don’t care for that one.” The chances of getting a balanced diet are very slim.

Jesus prayed “that they all may be one, as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You; that they also may be one in us, that the world may believe that You sent Me.” John 17:21 How is a seeker to know what true Christianity really is? For most people it’s now “cafeteria style” Christianity. “Ooh, I like this dish. I don’t care for that one.” The chances of getting a balanced diet are very slim.

And the Holy Orthodox Church and Apostolic Christianity now look like just another denomination, one of the many choices. Which, since the title of this series is “Orthodoxy and Other Faiths”, leads to a brief diversion:

Orthodox unity?

Someone asked me: How can we Orthodox complain about Protestant disunity when we ourselves are so divided? How can we speak about “one Orthodox Church” when we have so many different Orthodox “jurisdictions”, as we call them? Yes, we Orthodox have always been organized by nations and regions, which in the “old countries” are not in competition with each other *, since each covers a separate geographical area. However unplanned Orthodox immigration into Western Europe and the New World has led to many overlying Orthodox jurisdictions. This is a mess which causes much confusion. Pray that the Holy Spirit will lead us into one North American Orthodox Church.

- except at the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem where Orthodox squabbling is an embarrassment to us all.

But here’s the point: Despite our jurisdictional divisions we Eastern Orthodox are completely  at one in the things that really matter: the Faith, the sacraments, our worship, the Christian life. Except for a few minuscule breakaways, we all are in Eucharistic union with each other. Orthodoxy is united.

at one in the things that really matter: the Faith, the sacraments, our worship, the Christian life. Except for a few minuscule breakaways, we all are in Eucharistic union with each other. Orthodoxy is united.

I tried to find an icon with all 250 million Orthodox in it (not possible – count for yourself), all united in the Faith.

In fact, when I was first looking at Orthodoxy, our organizational divisions made Orthodox unity seem miraculous to me. I visited the pastor of a local Greek Orthodox church and asked him “What’s the difference between you and the Russians?” I knew most Greeks had come to America because they were poor and didn’t want to starve, while most Russians were of the “intelligentsia” fleeing from Communist oppression. From my experience with Protestantism, I assumed this would result in many theological differences, probably even some new “Orthodox denominations”. So “what’s the difference…?” The Orthodox priest opened a Divine Liturgy book and said, “At the beginning of the Liturgy, we use these Antiphons, but they usually use those.” I asked, “What else?” He said “That’s about it.”

And as I was to learn, that truly is “about it”. Except for the language (English, Greek, Arabic, whatever) Orthodox worship is the same everywhere. From one end of the earth to the other, all Orthodox teachers and preachers proclaim the same things. Here there is no rebellion in the ranks about theology. I still occasionally look behind pillars to see if I can find a member of the Church who doesn’t believe the Creed, the Orthodox Faith as given, but in my 30 years in Orthodoxy I have never found any. In the 2nd century, Saint Ireneaus of Lyons said that is one of the characteristics of the authentic Church.

And that is what distinguishes the unity of Holy Orthodoxy from what we are going to look at now.

Modern Protestant Disunity

This is the last in our series on Orthodoxy and Other Faiths. I’m giving 5 long articles to Protestantism since it is so very complex. If you want to read the previous articles in this series, go to Posts 31, 32, 41, 42, 50, 54, 55, 56, 61 and 62. The latter 2 Posts on Classical Protestantism give the immediate background to this article.

I myself was Protestant for 50 years – Evangelical United Brethren, Methodist and Anglican – though I was one of those Anglicans who desperately try not to be Protestant. Nevertheless in what follows here I can’t imagine I’ve got everything right. Protestantism has so many varieties, and it changes so fast. So please correct me if I have made mistakes.

I’ve been pondering how to get a handle on the intricacies of latter-day Protestantism. Maybe it will help if we try to categorize Protestants the way they do. Maybe?

I tried to find a chart with all major Protestant denominations on it (not possible), all disagreeing about the faith. Sorry this is so blurry, but you can a general idea of the complexity.

Or maybe this would be simpler: There are 2 general categories of modern Protestants. When I call them “liberal” or “conservative” I’m referring to their theology and general approach to Christianity. (I’ll mention their politics in Part 2 of this article.)

First, there are Liberal Protestant denominations such as the United Church of Christ; most (but not all) Methodists; most Anglicans (called Episcopalians in the United States) whom I list as Protestants because of their origin and theological diversity (but there are many Anglicans who insist they are not Protestants, plus other Anglicans who are conservative Evangelical Protestants); most Presbyterians; some Lutherans; and a few independent “community churches”. These folks are tolerant of theological differences. They generally believe that “my truth is my truth, your truth is your truth”, no problem – except that they are intolerant of those who don’t see things this way. Also, keep in mind that most of these denominations were once theologically conservative, and some of their members still are.

Second, there are Conservative Protestant denominations (though not all conserving the same things) such as most (but not all) Baptists; most Lutherans (a few of whom say they are not Protestant); and the multitude of Evangelicals and independent “Bible churches”. All these groups disagree theologically (which is why they are separated from each other) and are usually intolerant of theological differences: “My truth is the truth”. However, some of their members are more open-minded than the teachings of their denomination would suggest.

There are also Quakers whose theology varies from church to church, and Adventists who (I think) don’t fit in quite anywhere, and some others. There are also “extra-Protestant” groups whom the Protestants say are not Protestant, such as the Mormons and Unitarians whom we’ll look at in 2 weeks. And undoubtedly I’ve missed some. Oh, yes, the Pentecostals.

Also, as I said, within most of these groups, there are members who disagree (often publicly) with their denominations but remain there for various reasons – family tradition, love of friends, desire to reform or renew the denomination in one way or another, or it’s just too much effort to change. So if we talk with them, they may or may not reflect the teachings of their denomination. Some years ago a young man visited our Saint Nicholas, Cedarburg, for a few weeks. He said that each member of his family, all of them Baptists, well educated and devout, had a different “take” theologically.

Did this help us get it straight? I didn’t think so. I tried. But this is a tangled web.

So how did what Martin Luther started come to this? Let’s do a little history – oversimplified.

The Rise of Protestant Liberalism

Up till the 19th century, the major Reformation denominations – Lutherans, Calvinists (Presbyterians), Baptists, Anglicans – still prevailed, though there had been some changes within them, and American Methodists had already broken with the Anglicans. All (except some Anglicans) were, I think, still classifiable as Conservative Protestants – though, as I said, they were not all conserving the same things. However, all except the Baptists formally adhered to the ecumenical Creed.

Then, beginning in the late 19th century, most Protestant denominations were greatly influenced by Biblical criticism. Biblical “criticism” is not what it sounds like. “Criticism” here meant simply analysis of the Scriptures and their origins, with the intent that the true meaning could be better understood. Some good came out of that, helping people in our modern rational age to accept the authenticity of the Scriptures and understand the authors’ original intentions. But there also came much evil. Almost every speculation about the Bible, even the wildest, was taken by someone as a serious possibility. The result was that great doubt about the Scriptures was planted in peoples’ minds.

For an extreme example,  Dr. Albert Schweitzer, a French-German New Testament scholar, concluded in his book The Quest for the Historical Jesus that “the Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the Kingdom of God, who founded the Kingdom of Heaven upon earth, and died to give his work its final consecration, never had any existence”. He had lost faith entirely, though he did accept Jesus as a teacher. So in order to do something worthwhile with his life, he became a doctor to the natives of Gabon in west Africa, where he lived out Christian ethics and idealism perhaps better than any man of his generation. All the rest were busy fighting about the Bible! And for good reason. Remember that classical Protestantism was based on “Sola Scriptura”. If the Bible “went”, there was nothing else left. What Protestants needed but didn’t have was the Church’s Tradition – the Fathers, the Liturgy – to guide them in interpreting the Scriptures.

Dr. Albert Schweitzer, a French-German New Testament scholar, concluded in his book The Quest for the Historical Jesus that “the Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the Kingdom of God, who founded the Kingdom of Heaven upon earth, and died to give his work its final consecration, never had any existence”. He had lost faith entirely, though he did accept Jesus as a teacher. So in order to do something worthwhile with his life, he became a doctor to the natives of Gabon in west Africa, where he lived out Christian ethics and idealism perhaps better than any man of his generation. All the rest were busy fighting about the Bible! And for good reason. Remember that classical Protestantism was based on “Sola Scriptura”. If the Bible “went”, there was nothing else left. What Protestants needed but didn’t have was the Church’s Tradition – the Fathers, the Liturgy – to guide them in interpreting the Scriptures.

The Results of Protestant Liberalism

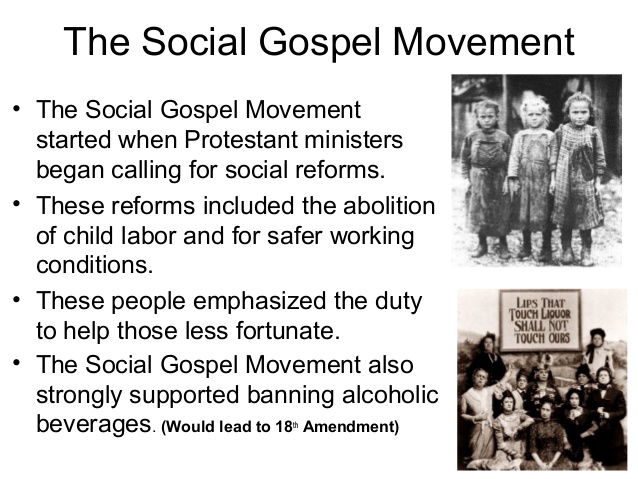

This doubt about the Holy Scriptures caused Bible, doctrine, worship and prayer to be played down in seminaries and schools – often replaced by what was called the Social Gospel, which accomplished many valuable social reforms which we should pray will not now be lost. (However, Social Gospel support for Prohibition of alcohol didn’t work out so well.)  This, of course, was a good thing. Christians should be all for it. We’re commanded by the Lord to love our neighbors – not only to save peoples’ souls, but also minister to their bodies, work for social justice and try to shape society for the better. But social service is not a substitute for prayer and worship. A solid faith in God, in Jesus Christ, the Holy Trinity, the Creed – this is the source of all good things, including strength and guidance for the Social Gospel. Many who supported the Social Gospel movement hoped that by their efforts the Kingdom of God would be built on earth. Events of the 20th century certainly dispelled that notion.

This, of course, was a good thing. Christians should be all for it. We’re commanded by the Lord to love our neighbors – not only to save peoples’ souls, but also minister to their bodies, work for social justice and try to shape society for the better. But social service is not a substitute for prayer and worship. A solid faith in God, in Jesus Christ, the Holy Trinity, the Creed – this is the source of all good things, including strength and guidance for the Social Gospel. Many who supported the Social Gospel movement hoped that by their efforts the Kingdom of God would be built on earth. Events of the 20th century certainly dispelled that notion.

The big problem came when this doubt about the Bible worked its way out into parish churches, and laypeople began to hear what was being taught, or rather not taught. Next week we’ll look what happened to these classical Protestant denominations by the mid-20th century.

The Rise of Protestant Fundamentalism

Back to the early 20th century. In reaction to this liberal “modernism”, some Protestants decided to “do another Martin Luther”. They left the mainline denominations and tried to return to the fundamentals of early Christianity – as they imagined them to be. They called themselves Fundamentalists. Christian Fundamentalism is not ancient; it’s a modern development. The problem with all fundamentalisms is that the past cannot be reconstructed hundreds of years later, as if nothing had existed between then and now.

Based on Reformation Protestant principles the Fundamentalists founded new churches and denominations based on “Bible alone”.  There have been many versions of what Fundamentalist principles are, so that it’s hard to know which list to choose. A good summary might be: 1 The inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures, which are to be taken “literally”, especially regarding the literal 6-day Creation, the miracles of the Virgin Birth of Christ, his bodily Resurrection, and his future physical return; 2 Belief in the substitutionary atonement of Christ – the idea that on the Cross Christ “paid the price of our sins” to the Father, thereby saving us from God having to send us to hell. (We looked briefly at this doctrine and its failings back in Blog post 36.)

There have been many versions of what Fundamentalist principles are, so that it’s hard to know which list to choose. A good summary might be: 1 The inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures, which are to be taken “literally”, especially regarding the literal 6-day Creation, the miracles of the Virgin Birth of Christ, his bodily Resurrection, and his future physical return; 2 Belief in the substitutionary atonement of Christ – the idea that on the Cross Christ “paid the price of our sins” to the Father, thereby saving us from God having to send us to hell. (We looked briefly at this doctrine and its failings back in Blog post 36.)

Over the years Fundamentalism has led to many odd things, both theological and political. But from the beginning Fundamentalists naturally had the same difficulties as those of the original Protestant Reformation. Without the guidance of the Church’s Tradition, how should the Scriptures be interpreted? What exactly did “literal” mean? The Virgin Birth and the Resurrection, no problem. But I think no Fundamentalists took “This is my Body, This is my Blood” literally. Nor, to be absurd, did any believe “I am the door” means that Jesus literally swung on hinges. But seriously, who decides these things? On what basis? And so the Fundamentalists went in all directions. New Fundamentalist groups broke away, one after the other after the other, each believing they had the true understanding of the Scriptures. And if they grew they became new denominations. All took for granted the Reformation principles of “Sola Scripture” and that new “churches” can be founded and claim to be “the true Church”. And so: the complete fragmentation of Protestantism.

And all I can say for myself, after researching, pondering, simplifying, condensing and writing of the complexities of Protestantism for this article is: “I am tired!”

This takes us up to more or less the mid-20th century. That’s where it gets easier for me, I think, I hope, for I was there!

Next week we’ll go on to look at Contemporary Protestantism, both conservative and liberal.

Week after Next: some extra-Protestant denominations

Fr. Bill,

Thank you for this facinating discussion on Protestantism! I grew up Baptist (a Black church, not Southern Baptist; we could dance!) and learning more about the history and continued divisions and creation of new denominations is fascinating to me! I became Orthodox 11 years ago, which was partially instigated by the break up and new creation of another church, because the pastor had a disagreement with the congregation and left. I am so grateful for the Orthodox faith, but I will acknowledge that I am also grateful for my Baptist upbringing, because I know it prepared me to be able to fully embrace the Church!!

Thank you, and I look forward to the next entry!

– Mary

Yes. I hope I didn’t in any way sound ungrateful for my background. Protestantism led me to Jesus Christ and gave me a social conscience. The Anglo-Catholic side of the Episcopal Church (before it fell apart) taught me the Faith. I thank God for it all.

The church is not united, and it has not been for 1500 years. There may be a Spiritual unity, but that remains to be seen (Physical). The Apostolic Church of Alexandria was somehow separated from the pentarchy. The Apostolic Church of Rome separated itself from the “pentarchy”. Breaking the Apostolic Faith is not One Faith, and the lack of communion of all causes one to question whether this is a true Eucharist in any. Should you partake in the Eucharist when you are divided and against your brother?

You’re right to be concerned about Christian divisions. (Orthodox would not say that the “Church” is divided.) However, you should refrain from the Eucharist only if you are personally at odds with someone and have not tried to make peace – not because of the faults of others over the centuries. Also: Orthodox don’t judge Eucharists as “true” or “false”, valid or invalid. None of our Eucharists approach the fullness of the Great Banquet in Heaven. If any sincerely seek Christ in Holy Communion, no matter where, no matter how, surely he will not deny them. So you should receive the Holy Eucharist in your tradition (I can’t tell what it is), and leave the rest to the Lord.