Here’s the humorous question with the obvious answer: “Is the Pope Catholic?” The Orthodox answer (to be uttered with a slight air of mystery in your voice) is ”Well… …?” Or sometimes we hear this from non-Orthodox folks: “You’re almost like the Catholics.” The proper Orthodox response (to be offered as humbly as possible) is this: “Actually we are the Catholics.” In both cases, this will leave people in total confusion.

Lets go back to the beginning.

That word “Catholic”

Did you know that “Catholic” is a Greek word? from κατά meaning “about” and ὅλος meaning the “whole”. So far as we know, it was first used by Saint Ignatius of Antioch about the year 110, in his letter to the Church in Smyrna: “Wherever the bishop shall appear there let [the people] also be, just as wherever Jesus Christ is there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful without the Bishop either to baptize or to celebrate a Eucharist.” Saint Ignatius was not referring to the Roman Catholic Church. The Pope of Rome had no jurisdiction over Antioch. Nor did he mean the “universal Church”, all Christians.

Saint Ignatius had an entirely different concept of what “Catholic” is. He was saying that when the Bishop (or someone authorized by him) and his people celebrate the Holy Eucharist, Christ is wholly present, and therefore his Church is wholly present. Orthodox see the Church not chiefly as an institution founded by Christ, but as the epiphany of something heavenly: Christ, his saints, his Kingdom. Ignatius was saying that at every authorized Divine Liturgy, the Church is manifested in its fullness, its catholicity.

The word “Catholic” also meant the “whole faith”. Already in Ignatius’ day, some believed only parts of the Faith. Catholic Christians were those who believed the whole thing, as opposed to those who did not. We still use the word in this way. But as time went on Catholic Christians in the East came to prefer the word “Orthodox” to describe ourselves. “Orthodox” in Greek means “right glory”, proper glorification of God. Though we insist on true doctrine, to us the Church is grounded not chiefly in correct theology (as important as that is) but in worship, true worship of God.

Today many use the the word “Catholic” to mean “Roman Catholic”. Don’t do that! Say “Roman Catholic”. This misuse reflects the later Roman Catholic claim that they alone are the one true Church, the only Catholics, that they alone hold the whole faith, that they have the only “valid” Eucharist, that to be saved one must be united under the authority of the Pope of Rome, the vicar of Christ. (Note that the documents of Vatican II modified these claims somewhat, but for centuries this was official Roman Catholic teaching and still was within living memory. Mine!) This was not what “Catholic” meant in the early Church. This is not how Orthodox should use the term.

How did we get into this situation?

The original place of the Bishop of Rome

At the apostolic council in Jerusalem (Acts 15), Saint Peter attended. He was chief of the apostles though not yet Bishop of Rome. Bishop James of Jerusalem presided and he, not Peter, announced the decision. That is, in accord with Saint Ignatius’ understanding, the local bishop took precedence. There was no hint that Peter claimed “universal jurisdiction”. The apostle Peter founded and presided at the Church of Antioch. Patriarchs of Antioch are successors of Peter, but they have never claimed universal jurisdiction over all Christians. In the early Church, Roman Catholics were Catholic Christians of the Diocese of Rome. Many even in the West (in Britain, for example) were not yet under papal jurisdiction, yet Rome recognized them and us as Catholic, as holding the fullness of the Faith, where the Eucharist in our local churches was “whole”. And we in the East recognized Rome as Catholic.

Anciently the Bishop of Rome was first in honor, because Rome was the imperial capitol and because Peter and Paul were martyred there. Saint Ignatius said in his letter to the Romans that the Bishop of Rome “presides in love”. This is how we Orthodox once accepted his “presidency” – and still could. The Bishop of Rome originally presided not by legal authority but by moral authority, by love. But by “universal jurisdiction”? No. We Orthodox believe we have maintained the early Church system, and that the Roman Church has changed over the centuries, that their style of presiding has changed from “love” to “ecclesiastical power”. This to the present day is the great difference between Orthodox and Roman Catholics.

How our differences developed

What follows here is a great oversimplification, skipping very much. (What else can you expect in a short article?) But I think it can help us understand why Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism grew apart.

Now, I do not think that the Bishop of Rome woke up one morning and said, “I know what let’s do: let’s invent some new doctrines and divide the Church!” Our differences developed gradually, and chiefly because of historical and cultural differences.

Pre-Christian Romans had long been organized and efficient. That’s why Rome’s empire lasted for centuries. Imperial Rome ruled in an authoritarian way. Law was clearly defined and enforced. Roman law and power kept everything under control. The Roman Church picked up on this style. Roman Catholic and most of western Christianity, as well as the western world, still function by means of law.

Meanwhile the East was less organized, less legal, at home with undefinable mysteries. Empires in the Christian homeland came and went. (Think of Alexander the Great.) Eastern Orthodoxy reflected that. Eastern Christians are less legalistic and more “flexible”, for want of a better word.

These were tendencies, not absolute, but you can see these differences to this day in things big and small, both secular and religious. Here are some examples.

1 Let’s begin with a secular example. In the western world the price in the store is fixed – pay it or not. In the East you haggle over it – it’s flexible. (A Palestinian man in my parish tried to negotiate for an item in Milwaukee’s Boston Store, to his wife’s great embarrassment. It worked! he saved himself about $100.) Just so, Roman Catholic Church law is fixed and almost immutable, even when it would make good sense to change it – priestly celibacy, for example. However, we Orthodox do things the way we do them, not because of Church law but because that’s the way we do them. Our canon laws haven’t been updated in centuries, and it’s a matter of opinion which ones should be followed. When I became Orthodox I was warned by a priest not to read canon law, for “it will only confuse you”! Our pastors may judiciously practice “economia” and ignore Church laws for peoples’ good. Roman Catholics speak much of “days of obligation”. Roman Catholic canon law says that if people miss Sunday Mass it’s mortal sin, and if they don’t confess it they pay for it in Purgatory. We don’t have “days of obligation”. Have you ever heard an Orthodox priest quote canon law at you? or tell you it was your legal “duty” to attend Sunday Liturgy?

2 In Roman Catholic practice, Confession is a legal transaction made to the priest for the purpose of remitting the penalty of sins. The priest says “by the authority granted me I forgive you”. Orthodox Confessions are therapeutic, made facing the icon of Christ with the priest as witness, for the purpose of helping people overcome sin and grow in faith and holiness. In the opening words, the Orthodox priest insists he has “no power to forgive sins,…but God alone”.

3 Roman Catholics see salvation chiefly as remission of the legal penalties for sin, so people won’t go to Hell. Indulgences provide a way to get a fixed amount of time off Purgatory. In the Latin West the Greek word δικαιοσύνε is translated “justification”, to be declared legally innocent. Orthodox translate the same word in the original sense, as “righteousness”. We see salvation as a process of growth into perfect goodness, the likeness of Christ. Orthodox don’t believe in Purgatory and think Indulgences are just bizarre.

4 The Roman Mass is usually concise: never say anything twice, get it done, do your duty and get out. I’ve heard that in Spain priests now can say Mass for vacationers in 11 minutes! Orthodox worship is mystical, contemplative, unhurried: “Again and again, let us pray to the Lord”; if three Kyrie eleisons are good, then twelve are better, and sometimes forty are still better. Our purpose is not to do our duty, but to be caught up into the mystery of God. Father John Meyendorff was once asked, “Why is the Orthodox Liturgy so long?” He answered, “Because our people like it that way.”

5 Roman Catholics are usually efficient. But if you expect an Orthodox to answer your letter quickly, good luck.

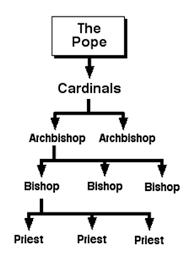

6 Romans Catholics see the Church as an  organization with the Pope at the top, and with “franchises” all over the world. In the East, we still see the Church in the apostolic “Ignatian” way as the manifestation of the heavenly Kingdom of God. Father Alexander Schmemann said it well: “To Orthodox the Church is not an institution with sacraments. It is a Sacrament with institutions.”

organization with the Pope at the top, and with “franchises” all over the world. In the East, we still see the Church in the apostolic “Ignatian” way as the manifestation of the heavenly Kingdom of God. Father Alexander Schmemann said it well: “To Orthodox the Church is not an institution with sacraments. It is a Sacrament with institutions.”

7 However, as we said at the beginning, the great difference between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism regards the authority of the Papacy. This also originally had historical and cultural causes. After the fall of Rome in AD 476, the Pope began to preside less “in love” but in a more authoritarian way. This was understandable. Western society was disintegrating, and the Church was threatened by pagans. Roman Catholics, with their more institutional view of the Church, began to see the Pope as the authoritative “vicar” of Christ, the representative of Christ for his earthly rule.

Then (and again during the plagues in the late Middle Ages), laity and even many clergy were poorly educated. Christianity in the West needed central authority to hold it together. In many cases Western Christians who were not yet under Papal jurisdiction accepted it gladly, for their own security. Likewise, there was no common source of civil authority in the West. The Emperor Constantine had moved east. So for the good of society, the Pope and the Roman Church became, as someone wrote, the “defining institution of western Europe”. This is how the Vatican States came to be, with a Vatican army which lasted into the 19th century, and why the Vatican today still is an independent political entity.

Because of all this the Roman Catholic Church progressively became less pastoral and more authoritarian. The Church now taught that Papal decrees and decisions of Church Councils were to be obeyed without question. They were working up to Papal infallibility. The decrees of Vatican II still told Roman Catholics precisely which Church laws are “infallible” and which are not.

Meanwhile in the East…

…things were very different. The Roman Empire continued, with the Emperor now in Constantinople, the “New Rome”. The imperial culture and security continued. Clergy and laity were well educated. Of the five original Patriarchates, four were in the East, so they had to function in a “conciliar” way. The Patriarch of Constantinople was given precedence, but had no legal jurisdiction over the others. Orthodoxy, with our very different view of the Church, has always said that Christ needs no vicar on earth to rule in his place, for he is already present in his Church, in all of us. Orthodox say Christ rules his Church from within it by love. No one in Orthodoxy is infallible except Christ, present in his Church, in his people, all of whom are guardians of the Faith. Thus Orthodoxy needs no authoritarian control system. The Patriarch of Constantinople is a good man, but he’s not infallible – guaranteed! Orthodox say Councils become authoritative only if the Church as a whole accepts them. If a genuine pan-Orthodox Council were to be held (don’t hold your breath) Orthodox, as always, would say “Hmm…”, and then eventually it would either be accepted – or not.

Here is how we Orthodox keep control: This is a true story: An Anglican had just seen a man who denied the resurrection ordained bishop. He asked an Orthodox visitor: “Could someone who denied the resurrection become a bishop in your Church?” The Orthodox answered “No”. The Anglican asked “Why not?”, wondering what was the Orthodox system of control – excomunication? ecclestical trial? The Orthodox man replied, “In my Church, if a bishop denied the resurrection, the people would take him and throw him into the river.”

Today we Orthodox believe firmly that, through no virtue of our own, we have preserved the original ways of Christianity without addition or subtraction, that we remain the authentic Catholic and Apostolic Church.

But let’s not overstate the case.

The differences between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism which I’ve described are not absolute. Indeed at times in the early centuries the Church of Rome was more dependably Orthodox theologically than were the Churches of Constantinople and Antioch. There have been many Roman Catholic mystics and contemplatives; one can even find a few efficient Orthodox. Some Roman Catholic bishops and pastors “preside in love”, while some Orthodox bishops and pastors have thought they were the Pope. Obviously there have been many Roman Catholic saints and holy men and women. We still agree on many, many things. Our differences originally were emphases which could have been held together in balance for the benefit of all.

However, these historical and cultural tendencies were already leading to major theological differences, which would result in the break between East and West. After that the Roman Church, believing itself to be the one true Church, felt free to go off on its own. Many innovations would follow.

So “Is the Pope Catholic?” Tune in next week for the answer to this question. Or maybe at the rate we’re going this will take two more weeks.

For previous articles in this series to go Blog Posts 31, 32, 41, 42 and 50.

Next Week: The Great Schism – what led up to it and what came out of it.

To say that the sacrament of confession is some kind of legal transaction in the Catholic Church is a gross misrepresentation.

Shayne, tell us more! Please explain. I’ve never been Roman Catholic, so I could be wrong. I’d like to know why.

I was Roman Catholic before I came into Holy Orthodoxy. I would say there are aspects of the sacrament of confession which were transactional, and some aspects that were more organic and similar to Orthodox confession. The transactional aspect is more an abstraction that one is only aware of if one thinks and reads. Sacraments in Roman Catholicism are presumed valid if they consist in three positive values of form, substance and intent. Proper form would consist of a contrite confession given to a valid priest who facilitates the confession, providing guidance. Substance would be the person giving confession performing contrition through penance given by the person who stands in persona Christi. And intent, well that should be obvious. One must intend with contrition, and be truly repentant.

In Orthodoxy I have never known a priest to give a formulaic explanation and this is understandable because we accept the sacrament as the mystery it is. Also I don’t think we have the concept of in persona Christi, as the priest states he stands as but a witness. Other than these differences the experience is similar but I think you get to know your father confessor much better, and vice versa, when confessing the Orthodox way which is more personal.

Thanks, Chris, for the clarifications. Was I was too influenced by pre-Vatican II movies? Or maybe by some ultra-conservative Lutherans here in Lutheran Wisconsin who, though they don’t practice Confession, have a very legalistic view of salvation (which I just assumed they got from Roman Catholicism): “Because of our sins God must condemn us to hell, but Jesus paid the price of our sins, so now we can go to heaven.”

Nice article. As a Catholic, Latin Rite, I would naturally quibble.

I do think that it might be good to explain that Roman Catholic as a term ( if it should be used at all which I would argue it really shouldn’t) leaves out the other 22 non-Roman Churches under the pastoral care of the Bishop of Rome.

I’m not Eastern Catholic but my friends who are really hate being called Roman Catholic. They go by Catholic, as do I.

But, again, nicely written article. You nail many of the attitudinal and historical reasons that allowed our enemy to shatter Christ’s Church.

Et Unam Sint.