The word in New Testament Greek is άσωτος/asotos, “dissipated, debauched, dissolute”. The old English word for this was “prodigal”. This guy who has wasted his life on nothing, worse than nothing, thrown away his family inheritance on pig’s slop: What kind of fuzzy-minded liberal would forgive somebody like that?

I still remember my granddad feeding the pigs. For the sake of you city and suburban people who never saw this:

Get the picture?

The Parable: Luke 15:11-32

I remember a professor in Methodist seminary telling us that “Christ’s’ parables have only one meaning. Don’t go digging for any more.” Wrong. This is a parable with at least three levels of interpretation.

I The Symbolic Meaning

Here’s a meaning that is not obvious to us, but would have been crystal clear to First Century Christians:

1 The Prodigal Son represents the Gentiles, created by God, given the world by God, but who long long ago went astray and wound up living far away from Him, feeding not on the bread of life, the pure word of God, but on strange teachings, living in debauched ways. Now, granted, there were good Gentiles who lived by high standards, philosophers who honestly sought the truth. But then read about ancient mythology and religious practice, and see how twisted and tormented it often was. Read about pagan deities and their sometimes horrendous demands. See how much of ancient popular life was spiritual husks and pods and worse. But the Gentiles now in the first century are seeing what they’ve been missing and are coming home to God: Greeks and Romans, Persians, some Indians, an Ethiopian – and soon many more.

2 The Father here is God, represented by His Church. I read that when Middle Eastern fathers had been offended against, it was appropriate for them to stand on principle. They waited for the offending son to come to them and beg forgiveness, and then perhaps… If this little Christian sect called the Church was going to take Gentiles in, then surely first they should stand on principle and insist on circumcision and adherence to the Jewish Law. But no. God through the Church was welcoming them back, no conditions required, except that they receive Baptism for the forgiveness of their sins – which they knew was ready and waiting for them. And then the Church invited them to the banquet – the Holy Eucharist, the foretaste of the Great Banquet in the Kingdom of God.

3 In this interpretation, who is the elder brother, who has “stayed home” and kept the rules and been obedient to God, and now is indignant to see all these “prodigals” entering the Church? The elder brother who won’t come to the party is the Jews, the Jewish nation. You’d think they would have been overjoyed that peoples from all over were now worshipping the true God, the only God, the God of the Jews. God’s promise to Abraham was now being fulfilled: More than the stars in the heavens or the grains of  sand along the seashore,… “A nation and a multitude of nations shall come from you, and kings shall come from you”. Genesis 35:11 Finally it was happening. Many peoples, soon-to-be many nations all over the world, were considering themselves spiritual heirs of the Jews – as do we. But no, the Jews were deeply offended that the Church was accepting these unworthy, prodigal Gentiles – and so they were missing the party, the joy.

sand along the seashore,… “A nation and a multitude of nations shall come from you, and kings shall come from you”. Genesis 35:11 Finally it was happening. Many peoples, soon-to-be many nations all over the world, were considering themselves spiritual heirs of the Jews – as do we. But no, the Jews were deeply offended that the Church was accepting these unworthy, prodigal Gentiles – and so they were missing the party, the joy.

As I say, the early Christians could not have missed this meaning of the Parable.

II The Practical Moral Application of the Parable

This is a teaching regarding our three kinds of relationships with people.

1 Sometimes I must play the role of the prodigal son. I have sinned. I have hurt people I love, who love me. What should I do? Like the prodigal son, I should pull myself together and go and apologize to them. Say “I’m sorry. Forgive me.” I do hope you’re not one of those people who just can’t say “I’m sorry”. Brothers and sisters, that needs to be said – for our sake, for the sake of those we’ve hurt. Acting it out isn’t enough, hoping people will guess that you’re sorry. No, don’t play games. Get it out. Deal with it openly. Now, perhaps you may decide it’s better to wait till the one you offended cools off a bit; play that by ear. But then be tough on yourself. Go and say “I’m sorry. Forgive me.”

2 On the other hand, sometimes we should play the role of the Father. You are the one who has been sinned against. Someone has hurt you. How should you handle it? Like the Father: Forgive. This is a hard thing to do. But we should always be prepared to do so, not only to do so, but…

Notice how the Father, even before his Son can say a word, hurries to meet him and hugs him, so that before his Son can say he’s sorry, he already knows he’s going to be forgiven. That’s how we should be with those who have hurt us. Make it easy on people who have offended you. If they’re showing any sign at all that they’re sorry and want to make up, make it clear that you will forgive. I’m convinced that very often people don’t apologize because they’re afraid to, afraid that if they do so they’re going to get dumped on, rejected. No. Be like the Father of the Prodigal Son.

So to repeat: If you’ve offended anyone, be tough on yourself: Say you’re sorry. If people have offended you, be easy on them: Make it clear you will forgive, and accept any sign from them that they’re sorry.

One simple way to do this is coming up in two weeks: Forgiveness Sunday, when the Church in her wisdom provides us a way both to apologize and also to open the door to those who are at odds with us. “Forgive me a sinner”. We’ll take a closer look at that Friday after next.

3 There may be situations where you’re tempted to be the older brother. It could be exactly the situation in the parable. A wandering family member has hurt the entire family, and then someone in the family makes peace with him – and you do not approve, you refuse to forgive. Or it could be that someone who has hurt you personally wants to be forgiven. In every case, forgive! Do not be the elder brother, standing on your stupid pride, missing all the joy of kissing and making up. I see some political/social implications here. Maybe I’ll talk about that someday.

III The Parable is about our personal relationship with God – each of us.

1 I am the prodigal son. I have taken what God has given me, my inheritance which I did not earn, His time, His energy, His resources, and I have wasted so much of it. In my old age I look back and think: I could have done so much more. I could have become so much better a person than I am. I could have prayed so much more, could have learned so much more, done so much more good, been so much more sensitive to those who love me. During my long lifetime, I have spent too much time feeding on nothing much, sometimes worse, when I could have been feeding on wholesome things in God’s house. I know God will forgive me – He’s made that clear – but I need to tell Him that.

Here’s why we hear the Parable of the Prodigal Son on the Second Sunday of Pre-Lent: Lent is time once again for me, the prodigal son, to go back home to God my Father and say “Forgive me”.

2 And when we do, the Parable tells us that God always runs out to forgive us and welcome us home. Indeed, He already ran out to us in the person of our Lord Jesus Christ when He came to earth two thousand years ago, as He still comes to us. God our Father does not stand on His dignity. He did not have to wait for Someone to “pay the price of our sins” before He could forgive us, as some mistakenly see it. Read the Gospels. Jesus was forgiving peoples’ sins before his Crucifixion. And still He runs out to welcome us. He comes to us in the Holy Eucharist every Sunday. He comes to us in the sacrament of Repentance. I go to make my Confession, knowing that God will forgive me, that He has forgiven me. And there is the priest standing by the icon of Christ, waiting to assure me of God’s forgiveness. I need to ask for God’s forgiveness, but He makes it so easy for me to do it.

3 Now let’s say more about the elder brother. What was his problem? It was a natural reaction, but it was a stupid natural reaction. “I have served you well all these years and you never gave me a party. But now this guy who has wasted all your money on loose living and loose women comes home and you throw a big party for him. It’s not fair!” But “‘My son,’ the father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. How could we not celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’” But the elder brother refused to come to the party.

What was his problem? He didn’t understand his Father. God is not fair. God is merciful. God is loving. The elder son didn’t love like his father did. And so he missed the party.

Over the centuries God has welcomed many sinners, stragglers, former heretics, bad actors, peculiar people. We who have tried to be good and faithful to God – we come to church and fast and pray and work for the Church and give time and money to Church and charity. Sometimes it’s been tempting for us to fall into the “older brother syndrome”. What does God think He’s doing? what does the Church think she’s doing? One little ceremony and then they make a big fuss over these sinners, and they’re as welcome as I am “who have borne the burden and heat of the day”! It’s not fair.

I think of the time almost forty years ago when a group of over two thousand Evangelicals, led by Father Peter Gillquist, desired to be Orthodox. Our Antiochian Metropolitan Philip (of thrice-blessed memory) checked them out and then, like the father in the Parable, said “Welcome home!” and there was a great celebration. I wonder how many cradle Orthodox reacted to this? people who had been faithful to the Church all their lives, given so much of their lives to the Church – I wonder how many of them were tempted to fall into the “elder brother syndrome”? “I’ve worked so hard for the Church, I’ve been so faithful, and now they’re making a big fuss over these newcomers. Not fair.” Though let me say also that when I came to the Antiochian Archdiocese, only two years later, I received only a warm and loving welcome. Many elder priests went out of their way to be kind to me. God bless our old-country Middle Eastern clergy!

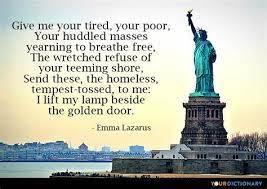

Another possibility: Could we apply this in a way to the social situation? I’m not trying to be political here. I don’t know the political solution to our present “immigrant crisis”, as it’s called.

However, it is accurately said that the United States is “a nation of immigrants”. We all came from somewhere else. Even the “native Americans” didn’t originate in North America. I know my ancestors came because they were poor as church mice and wanted a place where they could live free and provide for their families. All of us – either we ourselves or our ancestors – came here, worked very hard, made the difficult adjustment to a new culture and finally made a home here and have made great contributions to American society. I see it happening right now in my home parish, Saint Nicholas, Cedarburg, Wisconsin, where many first generation newcomers from the Middle East, kind, generous, loving people – some physicians, engineers, architects and others in more humble professions – all from “majority Muslim” countries. Thank God they were not turned away from the United States,

So how do many react when other suffering people also want to come here to escape persecution or make a new life for their families? Sometimes it’s “Americans for Americans only!” “Immigration is not a right!” “Immigrants, go home!” – said to immigrants, most of whom are devout Christians, by people whose ancestors were immigrants to America! As the old man said in the movie “Moonstruck”, “I’m confused….”

Back to the parable itself: The saddest part about this “older brother syndrome” is that there’s no love in it. There’s no mercy in it. There’s no joy in it. Here the father is throwing a big party. They’ve killed the fatted calf and they’re feasting on veal scallopini and veal parmesan, and the elder brother is sitting off in his room, complaining, hating it all, hating them all, missing the celebration, missing the joy. Up at the beginning I called him “stupid”. “Stupid: lack of good sense or judgment”.

Stupid, indeed. At the end of the Parable: Now who is throwing his life away on nothing? Now who is cut off from his father? Now who is the prodigal son?

Next Week. “In the Heart of the Desert” by Father John Chryssavgis

Week after Next: Forgiveness Sunday: what forgiveness is and what it is not