Let me say again that throughout this four-part series I draw often on the book The Fathers of the Eastern Church by Robert Payne.

The Council begins.

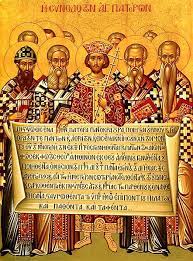

This First Ecumenical Council, the First Council of Nicaea, was not held in secret. We have five accounts of it.

The Council was held in a great marble hall above the beautiful Lake Askanios. In the center was a throne on which a Gospel book was placed. At one end sat the 318 (or so) bishops; at the other end was a throne for the Emperor. This is how Constantine saw it: the Gospel in the center, but the Emperor sitting a little higher than the bishops!

The Council was held in a great marble hall above the beautiful Lake Askanios. In the center was a throne on which a Gospel book was placed. At one end sat the 318 (or so) bishops; at the other end was a throne for the Emperor. This is how Constantine saw it: the Gospel in the center, but the Emperor sitting a little higher than the bishops!

Public domain

Early in the morning on the Sunday after the Ascension, forty three days after Pascha in the year 325, the bishops awaited the arrival of the emperor. Few of them had ever even seen an emperor. Most Christians who had stood before recent emperors had not survived.

Constantine entered, dressed in purple and jewels. He was 51 but he looked younger, tall, vigorous, with longer hair, a very short beard, bright eyes. He walked slowly to his throne, apparently deeply moved at the presence of so many holy men. Contrary to all imperial precedent he did not sit until he had asked their permission.

Constantine entered, dressed in purple and jewels. He was 51 but he looked younger, tall, vigorous, with longer hair, a very short beard, bright eyes. He walked slowly to his throne, apparently deeply moved at the presence of so many holy men. Contrary to all imperial precedent he did not sit until he had asked their permission.

Constantine, marble sculpture, c AD 350

First he spoke flatteringly to the bishops. Then he then begged them: Your dissensions are “more dangerous than war and other conflicts; they bring me more grief than anything else… I entreat you therefore, beloved ministers of God, to remove the causes of dissension among you and establish peace”. (Good advice, brothers and sisters.) Then he did something dramatic. He took all the letters that had been sent to him and, since he knew there was great bitterness in them, had them burnt. (Another good idea. I’m as guilty as the next guy about this… but really, most letters and e-mails written in indignation or anger, whether about political issues or religious matters or whatever, should be ignored. They do more harm than good. Don’t read them. Burn them. Or Delete!) Said Constantine, “I have not read them.” (I don’t know if he was telling the truth or not.) The emperor continued, “God will judge your complaints at the Last Day. I will hear your arguments in person” – and he certainly did.

Arians (there were not many) and Orthodox were immediately at each others’ throats, so that the Emperor could barely keep order. Neither of the two chief protagonists were bishops: the priest Arius and the young deacon Athanasios, both of Alexandria. Athanasios was in his early 20s, brilliant and militantly Orthodox. At that age he may already have written his classic book On the Incarnation. Arius was a gaunt, long haired ascetic man who always went barefoot. He had a disorder that caused occasional nervous spasms. He was morally upright; no scandal was ever connected to him – and, believe me, his enemies tried hard to find some. Arius spoke first and soon began to sing one of his pop songs: “There was a time when the Son was not”, to the horror of the Orthodox who began to cry out and stop their ears.

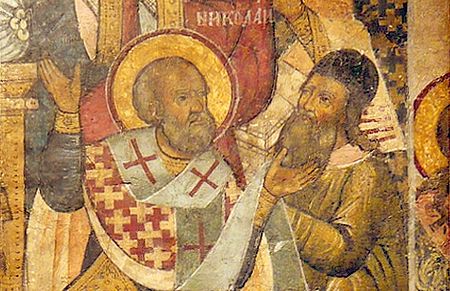

A legend says that Saint Nicholas of Myra was so angered that he rushed up and punched Arius, which caused him to be suspended from the epis copate for a time, and that explains why his name was not listed among those who attended the Council. It does seem odd, with Myra not very far away, that Bishop Nicholas would not attend. The story may or may not be true, but at least it has made a great action scene at the Church School Saint Nicholas Pageants at our Saint Nicholas Church in Cedarburg!

copate for a time, and that explains why his name was not listed among those who attended the Council. It does seem odd, with Myra not very far away, that Bishop Nicholas would not attend. The story may or may not be true, but at least it has made a great action scene at the Church School Saint Nicholas Pageants at our Saint Nicholas Church in Cedarburg!

This icon and the following one courtesy of Saint Isaac’s Skete at skete.com

The arguing and contention went on for days. How was it all to be resolved?

What the Council did not do

Some liberal theologians, denominations and books such as once-popular The Davinci Code have held that the early Church did not believe in Christ’s divinity, that Constantine and the Council imposed this doctrine on the Church; that the Council therefore suppressed older “lost gospels” about Jesus and imposed the Four Gospels alone on the Church. These claims are false and contradictory. As I said last week, the early Church took Christ’s divinity for granted. The first Christian to deny this was Arius. There were other early books (sometimes called “lost Gospels” – of Peter and Thomas and more) which the Church never accepted because they denied the humanity of Christ. These books were of Gnostic origin. Gnostics believed matter was evil, unworthy. They were “lost” long before the Council, apparently through disinterest. The Council did not suppress them.

What the Council actually did

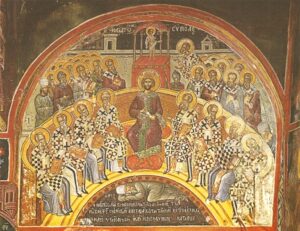

As the Council went on, it became obvious that, as in many controversies, those who made the most noise were few in number. After the issues were aired and the language clarified, the bishops (all except two, Theonas of Marmarica in Libya and Secundus of Ptolemais) agreed on what the Church had always taught, what the four original, authentic and universally accepted Gospels said, that Jesus was both God and Man. Finally Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea suggested that a common creed might express their unity. He recommended a beautiful statement of faith he had been taught as a boy in Palestine, which began “We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible, and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Word of God, God from God, Light from Light…” and so on. This Palestinian creed was reworked a bit, and the Council agreed.

So the first part of the Creed we say at every Divine Liturgy was written to defend the Church against Arianism: Jesus Christ is “true God of true God, begotten not created, of one essence with the Father; through him all things were made.” Take that, Arius! If Saint Nicholas didn’t punch him out, the Council certainly did! Arius was excommunicated from the Church. The Church doesn’t exclude people from receiving the Holy Eucharist for being wrong (we’re all frequently wrong) or for being sinners (we’re all sinners). The Fathers of the First Council cut Arius off for being wrong and unrepentant. They isolated him like a virus, till such time as he should repent and return to the faith. He never did.

From Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos, 16th century. That’s Arius at the bottom.

The Council ends.

The Council ends.

The Council completed its work on July 25. The emperor threw a great banquet for the bishops. (Our Church conventions and conferences still often conclude with a banquet.) Constantine complimented Athanasios for such wisdom coming from a young deacon. (We’ll hear more about him next week.) The emperor stood up to leave. On his way out he paid reverence to the bishops who had suffered at the hands of his predecessors; he kissed their empty eye sockets and their wounds and paralyzed limbs. He passed through a line of imperial bodyguards with drawn swords and left the hall, and the First Ecumenical Council was over.

Constantine and the bishops went home exhausted but relieved. The faith was established, and now the Church would be at peace…

…but it was not to be. Arius remained stubborn. He died, it was said in a privy (if you younger people don’t know what that is, just ask some of us old people) because of some sort of intestinal explosion, and there are some imaginative pictures of his death which you do not want to see. But Arianism did not die with him. It continued to grow and almost won the day. Fifty years later in Constantinople, the capitol, only one church remained Orthodox. All the rest had gone Arian. Arian missionaries went north and converted the Germanic tribes which were Arian for centuries, and as the tribes moved west and south they brought Arianism into western Europe. Arianism eventually faded out. Or maybe it just went underground, because it has revived in the last couple of centuries, and many of the modern Christians who have denied the divinity of Christ have been of Germanic, Anglo-Saxon origin.

Why did the decisions of the Council not settle the issue?

Because councils are not considered ecumenical, that is of universal authority, just because the bishops have approved something. The early Church was not like modern Roman Catholicism, where (in principle at least) the Pope speaks and that’s it: Now obey! In the early Church and in the Orthodox Church yet today, we understand that bishops can err, that there have been false and heretical councils. Councils are called ecumenical because the people of the Church, led by the bishops, finally recognize them as speaking the truth and accept them. The Holy Spirit dwells in all of us, and all Orthodox Christians are defenders of the faith. It’s a messy system, but it works. Look at the theological and liturgical unity of the Orthodox Church today, compared to the rest of Christianity.

In time the tumult and the shouting died, anger and hostility settled down, and it became obvious to almost everybody that Arius had been wrong, that the Fathers of the First Council of Nicaea had been right, that Jesus Christ is “God from God, Light from Light, begotten not made, of one essence with the Father by whom all things were made”, and the truth of Orthodoxy triumphed as it always does, and peace was restored as it always is. But sometimes it takes a while.

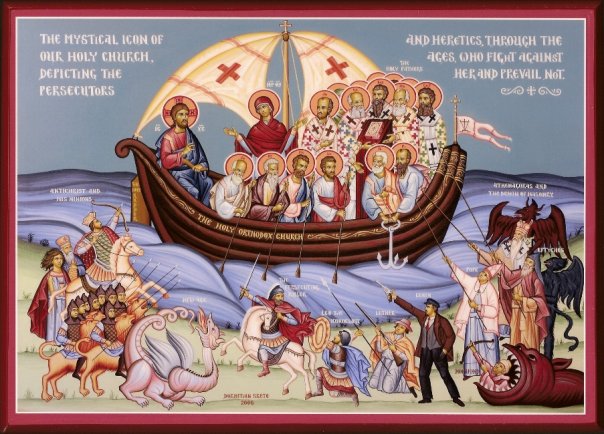

The Holy Orthodox-Catholic Church sails on unto ages of ages. Amen.

The Holy Orthodox-Catholic Church sails on unto ages of ages. Amen.

Next Week: The Story of Saint Athanasios the Great

Week after next: On the Road Again – My Travels resume

I definitely appreciate the explanation about ecumenical councils, Father! Seems to be a very misunderstood aspect of our Faith and history.

What’s the icon called? i’m curious to see who all is depicted at the bottom.

This uncommon icon goes by various titles including “The Mystic Church”. All I know is that I found it online the other day and liked it. Like many such images, this particular one has vanished already. The writing at the bottom is too fuzzy for me to make out. I think the dragon of the imperial persecutions is at the lower left. There are some Roman Catholic bishops at the lower right. I wonder who is the man to the near right in the late 19th or early 20th century outfit. Any ideas?

Lenin. His name is (barely) legible if you zoom in several times. The man kneeling in front of him is Luther.

Hmm…so why would Luther be kneeling before Lenin? Any ideas?

Father

I was serving near Uskudar (Nicea) in the early 1960s and used to drive by the site of Nicea 1 regularly. I am now writing my “Cold War Memoirs” and decided to include some background on the Council. Especially the first 3 centuries of Christianity. Your Blog has been most helpful. Especially the part about Constantine’s departure from the Council towards the end of this piece. Gave me chills! Wonderful. Thank you ! We lived in Istanbul. Had a young family so never made our dream trip to nearby Ephesus or the bus trip to Jerusalem. Many of our neighbors did.

Commander John Murphy, USN Ret.

Notre Dame Class of 1955

Gettysburg, PA.

John, thank you very much. As I mentioned in the preceding Blog post on the Emperor Constantine, I borrowed much of my material from the book “The Holy Fire” by Robert Payne, simplifying and omitting much for the purpose of having a short article. It’s an excellent very readable introduction to the Eastern Fathers. If you should get a copy, be sure to read the Preface by Father Thomas Hopko, who points out a few errors in the book.